Matthew Gregory Lewis (1775-1818) was described by his friend, Romantic poet Lord Byron, as both ‘an excellent man’ and ‘tedious, as well as contradictory, to everything and everybody’.[1] Lewis’ own journal presents a similarly paradoxical image: an owner of five hundred enslaved people who criticised the slave trade whilst extolling his own virtues as a compassionate ‘master’. That Lewis found it possible to reconcile such an existence is testament to the pervasive nature of the slave trade and the widespread acceptance of racist views.

Lewis was born to parents Matthew Lewis and Frances Maria. His father was an absentee slave owner, with land in Jamaica, as well as both Chief Clerk and Deputy Secretary at War in the War Office. Lewis’ parents separated when he was six years old, and despite the adulterous scandal in which his mother was embroiled, she maintained her son’s loyalty. Before turning eight years old, Lewis entered Westminster School in June 1783 as a Town Boy. The atmosphere of Westminster would have been relatively familiar to him, coming from Marylebone Seminary, a preparatory school where boys were only permitted to converse with one another in French and subsequent entry to Westminster was common.

While at Westminster, Lewis was noted for two performances in the Town Boys’ plays – as Faulconbridge in Shakespeare’s King John and as the Duke in Townley’s High Life Below Stairs. The latter play was a farce centred around a white Jamaican landowner returning from a trip abroad and featured a black character who would have been played by a white actor in blackface. That such a play was chosen to be performed by the Town Boys illustrates the typical attitudes towards race and slave-ownership with which Lewis was raised.

Leaving Westminster for Christ Church, Oxford in 1790, Lewis spent a large portion of his university years writing and travelling. Having followed his route through Westminster and to Oxford, Lewis’ father had hopes his son would embark upon a diplomatic career akin to his own, but Lewis was, self-admittedly, ‘horribly bit by the rage of writing’.[2] He had already penned two plays – a farce, The Epistolary Intrigue, and a comedy, The East Indian – as well as a two-part novel entitled The effusions of sensibility, or, Letters from Lady Honorina Harrow-Heart to Miss Sophonisba Simper. The latter exists only as fragmentary quotations in an early biography, with biographer Louis F. Peck suggesting the juvenile author’s age made itself clear in the text:

‘Although precociously shrewd in its appreciation of feminine vanity and social foible, it relied for humour principally upon extravagant periphrases and crude comic intent. A reader will not regret that only thirty pages of the manuscript survive’.[3]

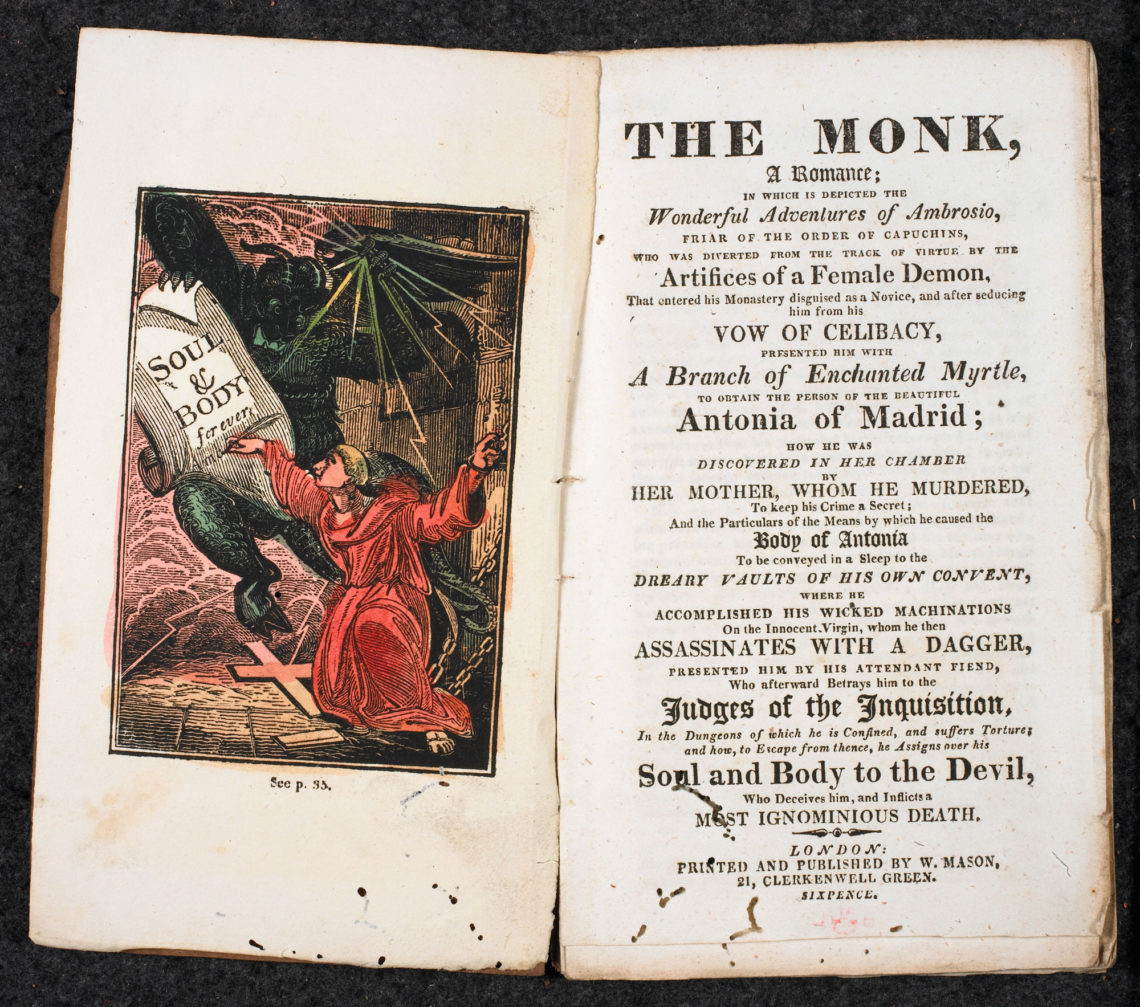

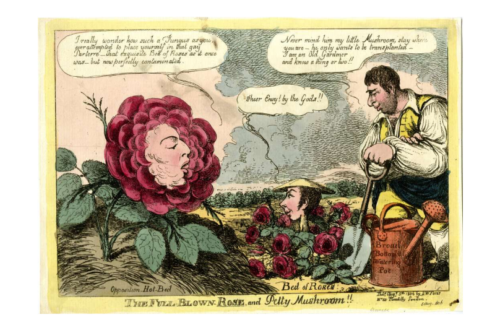

Despite a lack of success with his early work, Lewis continued to write, publishing The Monk in 1795. He claimed, in a letter to his mother a year earlier, to have written the entire novel in the space of ten weeks, and professed his pride in the work. Despite this, the first edition was published under his initials only. An English Gothic novel, The Monk draws from German sources and shocked audiences with its themes of the supernatural and sexual transgression. In response to positive reviews, a second edition was prepared, to which Lewis added not only his name but also his title as MP of Hindon, Wiltshire. This second edition met with uproar, and complaints of plagiarism and immorality. By the time a fourth edition was published, Lewis stripped out what he believed to be the more provocative elements. It was the scandalous content, however, that fed the book’s popularity and thus assured it a place in the English Gothic canon.

Lewis’ newfound success not only earned him the nickname ‘Monk’, but also an impressive circle of associates, including Robert Southey, Walter Scott, Goethe, Lord Byron, Mary and Percy Shelley. He continued to write, with his plays being erformed at Drury Lane and Covent Garden. With the money he made from book sales and play profits, Lewis was able to provide for his mother.

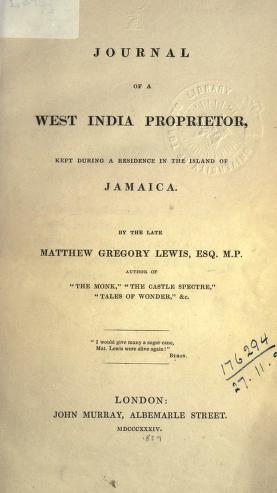

When his father died in 1812, Lewis was left the entire estate. He published no further works in his lifetime and took charge of the family’s financial affairs. In 1815, he sailed for Jamaica to visit the plantations he had inherited – Westmoreland and Hordley, together home to over 400 enslaved people. While travelling, Lewis kept a journal that would later be posthumously published as Journal of a West India Proprietor, detailing his experiences in the country and on his plantations.

It is evident from his writing that Lewis saw himself as a particularly benevolent slave owner. He considered the slave trade itself to be ‘execrable’,[4] did not order the enslaved people on his estates to go to church on Sundays, and banned the use of whips. For all of these acts he greatly complimented himself, but yet remained oblivious to his pervading racism, and the incongruity of slave ownership and moral righteousness.

Throughout his journal, Lewis demeans and negatively stereotypes the enslaved people on his estates. In referring to them with sweeping generalizations, such as ‘as the negroes are extremely suspicious, and very much afraid of ghosts’[5] and ‘the negroes are so obstinate and so wilful in their general character’,[6] Lewis isolates and compartmentalises people of colour as Other. There is also clear commodification of enslaved people, during both Lewis’ 1815 and 1817 trips. With the abolition of the slave trade, there was a concern that birth rates on plantations were not high enough to sustain the estates indefinitely. Lewis provided medals and accolades for enslaved women who gave birth to multiple children, and expressed his dissatisfaction with a Black man who worked in his household for having a wife not of the estate: ‘Instead of having a wife on the estate, he keeps one at the Bay, so that his children will not belong to me’.[7]

It is clear that Lewis’ progressive views, as he saw them, do not represent anything close to equality, and ultimately, he maintained the enslaved people on his plantations until his death. On his journey back from Jamaica in May 1818 aboard the Sir Godfrey Webster, he died from yellow fever and was buried at sea, leaving two plantations and several hundred enslaved people. Lewis had no children of his own and never married, leaving his Jamaican estates to his sisters. The plantations were still home to enslaved people in 1833, when claims were filed upon the abolition of slavery in the British Empire.

[1] Matthew Gregory Lewis. The History of Parliament. http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/lewis-matthew-gregory-1775-1818.

[2] Matthew Gregory Lewis. The History of Parliament.

[3] Louis F. Peck, 1961. A Life of Matthew G. Lewis, USA: Harvard University Press, p. 10.

[4] Matthew Gregory Lewis, 1834, Journal of a West India Proprietor, London: John Murray, p. 100.

[5] Lewis, Journal of a West India Proprietor, p. 98.

[6] Lewis, Journal of a West India Proprietor, p. 300.

[7] Lewis, Journal of a West India Proprietor, p. 142-3.