Article by Elizabeth Wells, Archivist, first published in The Camden, 2019

After pornography, the most-visited category of websites on the internet are dedicated to genealogy, the hobby of tracing one’s family history. Who Do You Think You Are?, a television show in which celebrities investigate their ancestors, is one of the BBC’s most popular documentaries – with 15 series and episodes regularly clocking six million views. Its success has stretched abroad too, with 17 international adaptations. There has even been a spin-off series, following the discovery, on the show, that working-class EastEnders star, Danny Dyer, is descended from Edward III. Danny Dyer’s Right Royal Family sees the actor investigating his noble ancestry and learning more about how they lived.

People are also turning to science to learn more about their family’s past. The personal genetic testing company, 23 and Me which offers ancestry-related information from DNA analysis has been used by over 5 million people. The data provided is not without flaws. Historically, biomedical research has focused on participants of European descent, and as the majority of 23 and Me’s users have unmixed European ancestry, the company cannot provide the same level of granularity in its reports to customers of Asian or African descent.

As an archivist, I encounter many individuals who are researching family history. But despite, or perhaps because of, its popularity, a lot of archivists and professional historians treat these ‘hobbyists’ with disdain. On my first visit to an archive as part of post-GCSE work experience, my mentor sneeringly muttered ‘ancestor worshippers’ as we passed a group of family historians. At a party recently, some fellow archivists declared that they felt genealogists should be banned from using archives, or at the very least charged exorbitant fees. ‘They’re just a bunch of bored, solipsistic, baby boomers sucking the life out of the young…as usual!’ my friend declared.

The situation is awkward for me as I harbour a guilty secret – my parents are both keen amateur genealogists. They have spent years gradually unravelling their, and therefore my, ancestry, painstakingly going back to the 16th and 17th centuries along some lines. Soon after I got engaged my father began researching my fiancé, Tom’s, family history. Tom was horrified by this intrusion, but my father felt he had struck gold. With his own forbearers, the research process had been slow and laborious, checking through parish registers and regularly hitting dead ends as he uncovered poorly documented, resolutely middling-sorts of ancestor. With my husband’s family, a few hours googling enabled him to draw up a family tree connecting him via direct descent to royal families across Europe along with connections to well-known historical figures like Jane Austen and El Cid. I was stuck in the middle, trying to mediate between my father’s enthusiasm and my husband’s embarrassment. And what did I think about it? I’m still trying to decide.

There is no denying that we live in a society where hereditary privilege continues to exert not only significant influence, but also fascination. As a constitutional monarchy, with hereditary peers sitting in the House of Lords, our democracy is still influenced by those born into power. Nor is hereditary privilege the preserve of Conservatives; on the left new dynasties are being formed – four generations of the Benn family have been Labour politicians. A recent study found that those living in England with Norman surnames, likely descended from the victors of the 1066 invasion, are generally wealthier with longer life-expectancies than those with artisanal surnames such as ‘Smith’ or ‘Carpenter’.

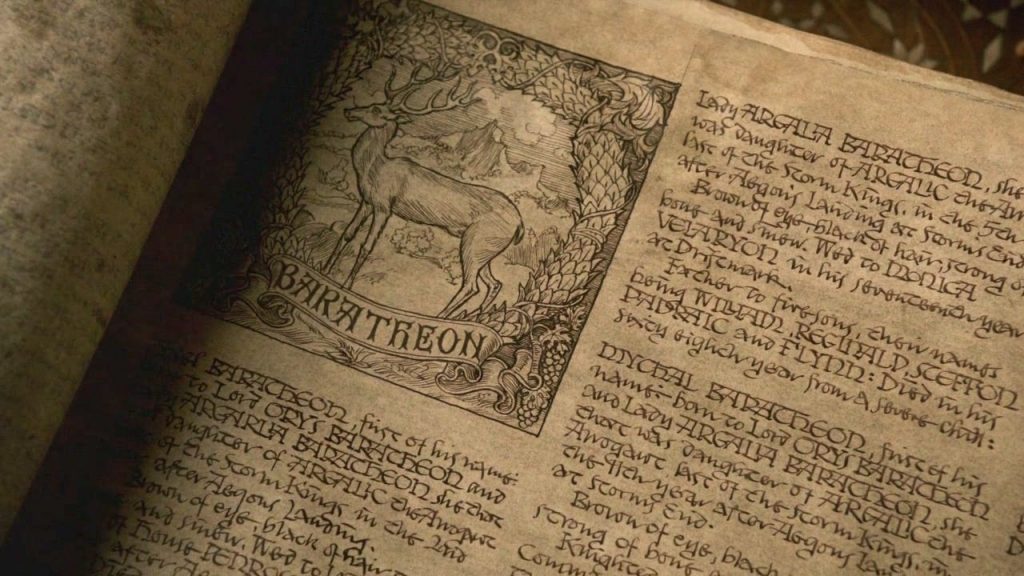

Even in popular culture, we are preoccupied with genealogy. J.K. Rowling often plays with ancestry in her narratives. In the Harry Potter world, Rowling simultaneously subverts our assumptions about inheritance, undermining those characters preoccupied with purity of blood, whilst endowing many of her protagonists with a complex web of distinguished antecedents. Meanwhile, on television, millions are anticipating the revelation of Jon Snow’s parentage as competing dynasties battle it out in Game of Thrones.

As a society where the majority claim to support greater equality, our excessive concern with ancestry, particularly if that ancestry is illustrious, is worrying. It is disconcerting to think that the shapes of our lives are predetermined by small portions of DNA shared with distant relations we have never met. The desire to feel connected with ones forebears often results in individuals mistaking shared experiences and coincidences as evidence of inherited characteristics. When interviewed about his ancestor, Thomas Cromwell, Danny Dyer noted a number of similarities: ‘He came from a slum, I come from a slum; Cromwell left the country at 14, I started acting at 14; He was a self-taught lawyer. I’m a self-taught actor…Cromwell wrote his last letter to Henry VIII begging for his life, on July 24, which is my birthday.’

This cherry-picking approach to the past – very few celebrities find themselves identifying with their ancestors’ less appealing traits– is concerning. Ben Affleck, who featured on the American show Finding Your Roots, lobbied producers to omit ‘embarrassing’ details about his slave-owning ancestors.

More alarming is the short leap it takes to go from the idea that an individual’s positive qualities derive from their distant ancestry to a sense that those with eminent ancestors are entitled to higher status. That so many in positions of influence in our society come from distinguished families is evidence of how entrenched privilege is, and not a justification of it.

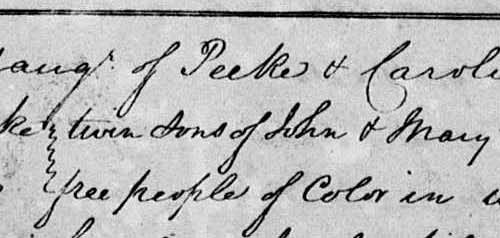

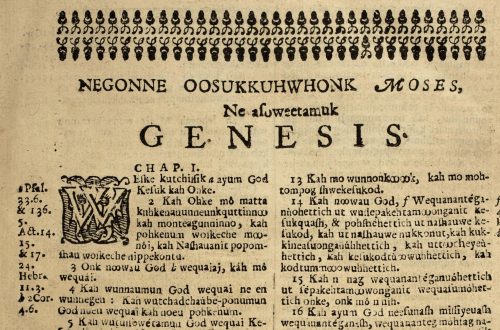

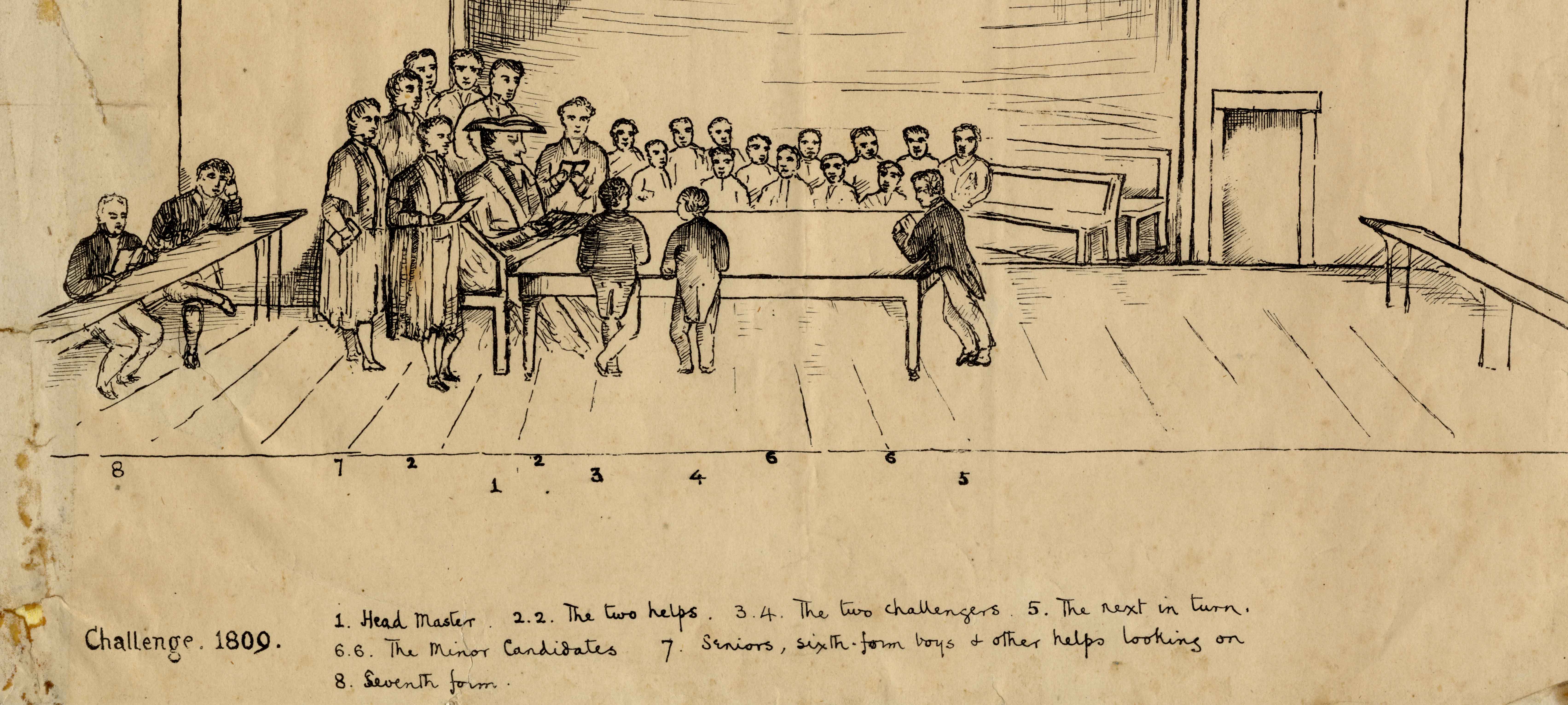

However, I can see the draw of wanting to learn about one’s ancestry. Not out of a self-obsessed and misguided notion that learning about your ancestors helps you to better understand your own character. At its best, family history can be a means of uncovering the lost stories of ordinary people, a window into social history, rather than annals of kings and queens.

Perhaps the most striking element of genealogy is the inverted tree shape, which suggests that hundreds of ancestors culminate in a single individual. One of the unanticipated positives of DNA genealogy, is that it has led people to reach out to others who share their genetic material and form new friendships. Remembering that we are all connected to one another is no bad thing.