It likely comes as no surprise that the history of Westminster School is dominated by white men. For the majority of our history there has been limited diversity amongst our pupils. It is difficult to single out an individual as the first to break the long line of racial homogeneity but Robert Dalzell perhaps stands as a contender. In The Record of Old Westminsters, the School’s biographical dictionary of all known alumni, his entry was sparse. It listed a year he was known to have been at the School, some details of his time at university and his marriage, however it lacked a date of birth or death and came with the blunt caveat ‘This […] entry need[s] sorting out.’

It was only by accident that Dalzell came to our attention. While searching for Old Westminsters with links to the Slave Trade so these associations could be added to their biographies, his name was flagged up. He inherited half of a Jamaican estate and its enslaved people on his father’s death around 1756 and benefited financially from it until the sale of his interests in the property 44 years later.[1] The UCL Legacies of British Slave-ownership database has been an incredibly valuable resource in tracing more than 80 Old Westminsters with links to the Slave Trade. One vital piece of information it provided for Dalzell was his mother’s name, which was previously unmentioned in the School’s records: Susanna Augier.

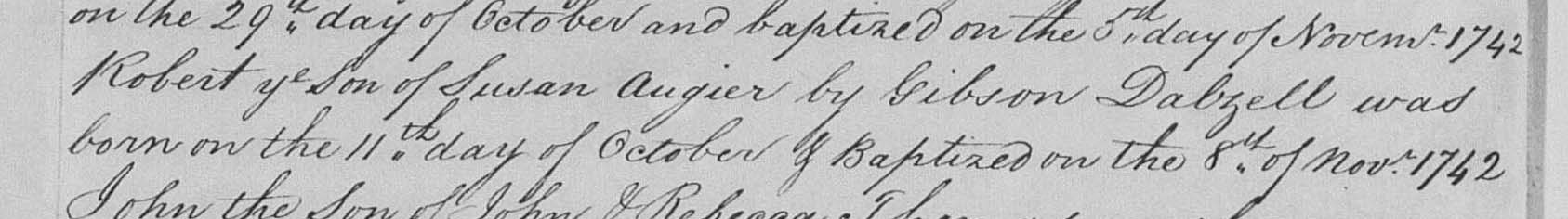

Augier was born an enslaved person to an unknown black mother and a white planter, John Augier, whose surname she adopted. On John’s death in around 1722, Augier and her four sisters were manumitted (freed) in accordance with his will. She went on to have three children with white planter Peter Caillard in Kingston, Jamaica, named Mary, Peter and Susanna Caillard. When their father died around 1728, Augier was left with a vast amount of property across Jamaica, in Kingston, Spanish Town and St Catherine. Within a year she was living with Gibson Dalzell, a man with whom she had two further children, Frances (b. 1729) and Robert (b. 1742). In 1738, before Robert Dalzell’s birth but after the untimely deaths of Peter and Susanna Caillard, Augier applied on behalf of herself and her surviving daughters, Mary and Frances, for the legal status of whites. This was granted by a Private Act of the Jamaica Assembly on July 19th of that year and thus when Robert was born four years later, he shared this status.

Augier was exceptionally successful for an unmarried woman in Jamaica and her inherited wealth and skill at managing it clearly presented a threat to white Jamaican landowners, who used her case in support of a 1761 Act that limited inheritance available to black, mixed race and illegitimate Jamaicans to £2,000.[2] From Caillard alone, Augier had acquired lands worth £26,150 8s 1d, entailed for her two eldest then surviving children, Mary and Peter. By 1752 she owned 950 acres of land and had 80 enslaved people and one white servant.[3] She also inherited a life interest in Dalzell’s estate, worth £6854 1s 3d, upon his death in around 1756. It appears that she remained in Jamaica and was buried in Kingston in February 1757.

Frances and Robert Dalzell were raised from an unknown age in London on Clifford Street, Mayfair by their father. Frances would go on to marry into the Scottish aristocracy in 1757 and one year later her younger brother is known to have been at Westminster School, although he could well have been there earlier. Unfortunately, very little is known about Dalzell’s time at the School. He was not a scholar, but records of Town Boys (pupils who were not scholars) are incomplete and contingent on the good record-keeping of Head Masters. One of the most significant gaps is between February 1753 and May 1764, under Dr. William Markham, which is when references to Dalzell would appear, based on external sources that identify him as a pupil. It seems likely, drawing on information from his father and grandfather’s wills, that he joined the school shortly after his father’s death in 1756 and remained there until at least 1758.

His presence at the School precedes The Elizabethan (the School’s magazine) by over a century, and the Town Boy Ledgers (logs kept by the Head Town Boy of events deemed significant) began only six years prior to his death, long after he had left the School. Whether Dalzell’s ancestry was identified by the other boys and masters and, if so, whether he was treated poorly because of it, is unknown. It seems that he considered the School a valuable place of learning, irrespective of his personal experiences, as we know his grandson, another Robert Dalzell, was admitted to the School in 1806 and became a King’s Scholar in 1809.

While we can’t know what Dalzell’s experience at Westminster was like based on extant records, it is possible to get a sense of the wider cultural attitudes at the time. His cousin Elizabeth Augier was the daughter of Susanna Augier’s sister Mary (with English merchant William Tyndall), and she went on to have nine children herself with a wealthy merchant by the name of John Morse. The Morse family found itself at the centre of an extended legal battle in 1781 when John Morse died and his nephew, Edward Morse (who had himself been a pupil at Westminster School and was possibly a contemporary of Robert Dalzell), took his own cousins to court over Morse’s inheritance. His reasoning was racially motivated and attempted to use the 1761 Jamaica law of inheritance restriction that had been passed in reaction to Susanna Augier’s impressive wealth. However, the laws of Jamaica didn’t extend to the British elite and the Morse children had the same status of whites that Robert Dalzell had, courtesy of an Act applied for and granted to their grandmother Mary, Susanna Augier’s sister. Edward Morse chose to ignore this Act that bestowed privileged status on his cousins, likely well aware it would complicate the race trial he was trying to construct. It was Edmund Green, the Morse family’s lawyer, who unravelled the complicated ancestry of the family and revealed the Act to the courts.

Edward Morse also made an unfounded claim that his uncle had been non compos mentis, or not of sound mind, when his will was written. The Morse children due to inherit were illegitimate, as John Morse and Elizabeth Augier were not married, but Morse had explicitly named them in his will and did intend for his estate to go to them. Had Edward Morse been able to successfully argue that his uncle’s will was written while he was not of wholly sound mind, he himself stood to inherit a large portion of the fortune, as a legitimate heir. It was not until January 1799 that the case was won in favour of the John Morse’s children and they could legally inherit their father’s fortune.

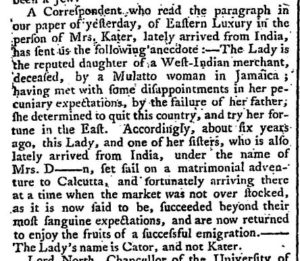

Edward Morse’s negative attitude towards his Jamaican family is accentuated by the claim that he may have been the author of an anonymous letter to the Morning Herald in 1786 which publicly defamed one of Morse’s daughters, Sarah Cator, by revealing her mother’s identity as a ‘Mulatto woman’,[4] thus intentionally damaging both Elizabeth Augier’s reputation and the reputations of all her children, who had been trying, rather successfully, to integrate into elite white British society. There was a growing stigma against people of colour in Britain and it was desirable to avoid widespread knowledge of any Black ancestors. It seems likely that Dalzell did not publicly reveal the identity of his mother, who was a well-known figure in Jamaica but less so in Britain, something made all the more easy by Augier’s remaining in Jamaica. Edward Morse would not have been alone in his prejudice and may well have espoused his views in Dalzell’s earshot, if they were indeed at Westminster together.

It would perhaps be wrong to name Robert Dalzell as Westminster School’s first Black pupil, if he would have rejected the label himself, but it is also a title that may not even belong to him. Daniel Livesay, author of the book Children of Uncertain Fortunes: Mixed-Race Jamaicans in Britain and the Atlantic Family, 1733-1833, suggests that ‘hundreds of children born to white planters and Caribbean women of colour […] crossed the ocean for educational opportunities’,[5] among other goals. Dalzell is not a unique figure as a mixed-race child raised in England and it is possible that, as the sons of wealthy white men, others could have found themselves crossing Little Dean’s Yard.

[1]“Robert Dalzell Of Wokingham. Summary of Individual | Legacies of British Slave-Ownership”. 2020. Ucl.ac.uk. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146644149.

[2] Powers, Anne. 2012. “Augier Or Hosier – Name Transformations”. A Parcel of Ribbons. http://aparcelofribbons.co.uk/2012/04/augier-or-hosier-name-transformations/.

[3] “Susanna Augier Or Hosier. Summary of Individual | Legacies of British Slave-Ownership”. 2020. Ucl.ac.uk. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146655511.

[4] Anonymous, Morning Herald, July 12, 1782, Issue 1782, http://find.gale.com/dvnw/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=DVNW&userGroupName=wschool&tabID=T003&docPage=article&docId=Z2000887328&type=multipage&contentSet=LTO&version=1.0.

[5] Livesay, Daniel. 2018. Children of Uncertain Fortunes: Mixed-Race Jamaicans In Britain And The Atlantic Family. 1st ed. United States of America: University of North Carolina Press.