Three members of the Fuller family attended Westminster School in the middle of the 18th Century – Henry (1724-c.1773), Peeke (c.1732-1798), and Charles Beckford (1739-1825). They were all born in Jamaica, where their father, Thomas Fuller, owned a total of 6,292 acres of land and 376 enslaved people, all of which was left to his three sons as tenants in common on his death in 1769. We know relatively little about the mens’ time at school, as is unfortunately the case with many pupils from this era. They were admitted in 1739, 1746 and 1747 respectively, and were Town Boys rather than Scholars. Henry left the school after four years and went on to study at Queen’s College, Oxford, while Peeke’s stay was likely shorter, joining in November at age 14 and leaving the following year. If he attended university, we have no record of it. Charles seems to have stayed the longest, admitted at age 8 and matriculating at Trinity College, Cambridge in 1758. We have no record of his leaving date, but neither do we have knowledge of him attending another school subsequent to Westminster.

It is Charles Beckford Fuller who is the most elusive the three brothers, not causing any major scandals that left an enduring mark. He kept his portion of his father’s estates until 1795, when he sold them to his surviving brother, making Peeke the sole owner of the lands and enslaved people in the West Indies. Charles appears to have moved back to England to live out his life in Hertfordshire. He died in 1825, outliving both Henry and Peeke by a considerable margin, and makes no mention of any Jamaican estates in his will, which names a ‘Sarah Gregory’ as his sole benefactor.

Although we don’t know when Henry Fuller, the eldest of the three brothers, returned to Jamaica after his education in the England, we can be certain that he did. When he died there in around 1773, his will suggested that he had been living in the country for some time. Within the document Henry freed a ‘Negro woman slave’ named Princess and gave her annuity of £10 Jamaican currency and also bequeathed Fanny, a ‘free Negro woman’ and daughter of Princess, an annuity of £20. This was not an uncommon custom – Thomas Fuller, Henry’s father, had freed three enslaved people in his own will and left them annuities. However, Henry also mentions two other people of colour in his will whose appearance is slightly more unusual – John and Ann Roberts, his ‘mulatto son and daughter’. They are recorded as his children ‘by the said free Negro woman named Fanny’ and each are bequeathed an annuity of £10 Jamaican currency until they reached the age of 21 and then, significantly, £300 with which to purchase their own enslaved people (six men for John, and two men and four women for Ann). These enslaved people were to assist John and Ann in the running of a small estate they were to be given. Henry’s will required that his:

‘executors within three months of my death to purchase a convenient piece of land containing about 25 acres of the value of £50 currency and that to be conveyed to John and Ann Roberts as tenants in common.’[1]

While a generous gesture towards children he could have abandoned without consequence, this portion of land was barely a fraction of the estates Henry Fuller had inherited. Regardless, it made Ann and John Roberts landowners. It was not unheard of at this time for white relatives to contest wills that left money to mixed-race relatives, but the executors, who included Henry’s brothers Peeke and Charles, appear to have carried out Henry’s wishes and purchased the land for his children. Peeke Fuller, in particular, seems to have been well-regarded by John Roberts, as his name is given as the middle name for all three of John’s traceable sons.

Unfortunately, there are sparse records of the two Roberts children – the origin of their surname marks the first mystery. It would have been unlikely for Fanny to have a second name, as she was almost certainly born into slavery and freed prior to the making of Henry Fuller’s will. She is given no surname in the will itself, whereas John and Ann notably are, which seems to suggest the name did not originate with their mother. There were numerous Roberts in Jamaica around the time of their births and it is possible the two children were given this name in order to hide, or at least contain, knowledge of the identity of their father. They were not ‘legally’ Henry’s children as he never married Fanny, thus naming them in his will was the only way to ensure provisions were made for them after his death.

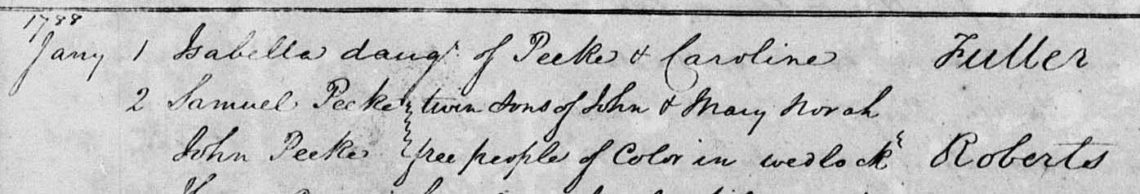

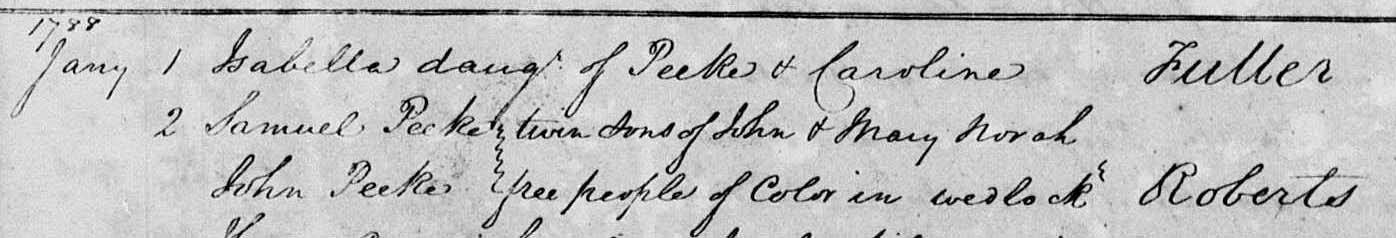

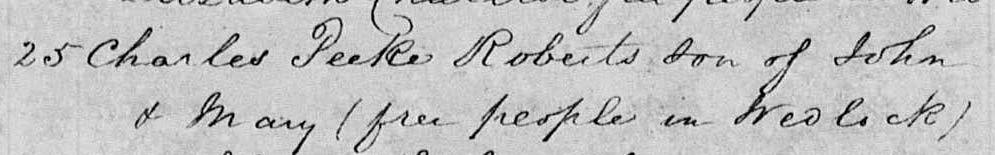

John Roberts seems to have married a Mary Norah Roberts, a ‘free negro’[2] and stayed living in Jamaica. They had at least three children together: twins John Peeke Roberts and Samuel Peeke Roberts (baptised in 1788), and Charles Peeke Roberts (bapt. 1790), all born in St. Catherine, Jamaica. Notably both Peeke and Charles Fuller are honoured in these names, suggesting that John was grateful for the treatment he received from his uncles, or at least wished to ingratiate and associate himself with them. Mary Norah Roberts died in 1799 and was buried August 6th, her cause of death not recorded. Two potential burial records for John Roberts exist – either July 2nd 1796, or December 9th 1797.

Ann Roberts may have been baptised on April 17th 1763 but beyond this it is difficult to conclusively make any claims about her life as if she had married she would likely have changed her surname. In 1783 a child was baptised in St Catherine, Jamaica to mother Ann Roberts and father ‘Roberts’. A husband taking Ann’s surname would be highly unlikely, but she may have wished to keep the child’s father’s identity a secret and use her own last name, perhaps pretending to be married. The possibility of this only increases when considering the name of the child: Caroline Christian Fuller Roberts. Not only is ‘Fuller’ present, but ‘Christian’ is the name given for Charles Beckford Fuller’s mother on his baptism record. From this point the Roberts and Fuller names often appear together in records. The exact line of descent is not always clear, however this would suggest that Ann and John Roberts acknowledged their connections to the Fuller family, and their descendants continued the tradition.

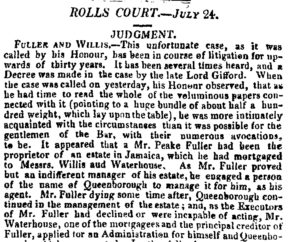

After Henry Fuller passed away he split his share of the estates equally between Peeke and Charles, leaving them each a moiety, or half, of their late father’s lands when combined with the portions they already held. When Charles sold his interests to Peeke this left him with the full estate up until his death in 1798. After Peeke’s death, however, the estates and the family were involved in a legal dispute that lasted thirty years. Recorded in court documents and newspaper articles, the case went through several appeals until finally being laid to rest in 1831. Reporters talk of ‘huge bundles’ of ‘voluminous papers’,[3] giving an insight into how complex the proceedings were, but the central matter of concern was the role played in the running of the estate by John Willis and Benjamin Waterhouse. The pair were successful Prize Agents in Jamaica, their firm accounting for 9 in every 10 prizes carried to Jamaica, worth in total upwards of £2,143,000. These ‘prizes’ were naval prize money, paid to sailors involved in the capture of ships or cargo belonging to the enemy in the Seven Years’ War. Prize Agents tended to be mercantile firms, charging 5% commission, but it is clear that a great number of them also made use of unclaimed prize money within their own businesses before returning it to Commissioners of Greenwich Hospital, as was required by law.

Peeke Fuller had mortgaged his Jamaican property to Willis and Waterhouse before his death, at the same time agreeing to make them consignees and furnishers of the estate. They were thus entitled to a percentage of profits, but also commission upon their consignments and the supplies they furnished. After Peeke’s death his estate was passed to his eldest son, Henry Augustus Fuller, and the estate’s manager, Samuel Queensborough, was kept on by Willis and Waterhouse’s recommendation. The Executors Peeke Fuller had named were either dead or considered ‘incapable of acting’, so Waterhouse applied for, and was granted, an Administration for himself and Queensborough. One year later a Bill was filed ‘praying an Account of the Management of the Estates, real and personal, of Mr Fuller’.[4] The suit professed to be filed for the benefit of the Fuller family, but it was argued in an rebuttal launched by Catherine Fuller, one of Peeke’s daughters, on behalf of her family that the suit was fraudulent and had been filed with the intention of giving the estate in its entirety to the mortgagee. The original decision of the Jamaican courts was indeed to give absolute control of the estate to the mortgagee, here Willis and Waterhouse, however this was only the beginning of a lengthy process of appeals.

After two lawsuits in the West Indies, the case moved to the UK in 1812. Judgements on the case were given by five different individuals, one of whom returned two opposing rulings at two different appeals. In 1831 the final appeal was launched whereupon it was argued that the original 1801 decision had been made by a competent court and thus should be considered binding as ‘no other court of a concurrent jurisdiction could question such a decree’.[5] The only way to challenge this decision would have been to prove the occurrence of fraud, which the Fuller family attempted to pursue. They highlighted a discrepancy on the original bill where Catherine Fuller was described as being a minor despite the fact she was actually of age, however her birthday had been in December with the bill filed January of the following year and it was simply considered likely that the bill had been drafted while she was indeed still a minor. Henry Augustus Fuller’s ability to manage his own estates was called into question, as his will had been signed by mark, rather than by a full signature, with the Fuller family arguing this suggested illiteracy, but they were countered by the argument that many highly literate men had signed their wills by way of mark, particularly if infirm at the time of writing them. Ultimately the final ruling of the courts in 1831 was the uphold the original decision made by their Jamaican counterparts and give the Fuller estates to the mortgagees.

The Fuller family was considered by The Standard newspaper in 1831 to be ‘reputable, numerous, and once wealthy’.[6] Thomas Fuller’s estates in Jamaica were certainly vast and the extent of his wealth is indisputable. It would take only two generations before his property fell out of the hands of his descendants. Rather than bequeath them any portion of the existing Fuller estates, Henry notably ordered for new land to be bought for John and Ann Roberts. The pair retained their positions as Jamaican landowners when their cousins did not, and this newly purchased land became all that was left of this branch of the Fuller family’s Jamaican property.

[1] Henry Fuller. Summary of Individual | Legacies of British Slave-Ownership”. 2020. Ucl.ac.uk. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146642791.

[2] ‘Jamaica, Church of England Paris Register Transcripts, 1664-1880’ index and images. Mary Norah Roberts, 1799. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939F-DZXW-G?i=151&cc=1827268&personaUrl=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3ACC48-9TW2

[3] Anonymous, Morning Chronicle Rolls Court, July 24 1827, Issue 18052, http://find.gale.com/dvnw/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=DVNW&userGroupName=wschool&tabID=T003&docPage=article&docId=BA3207142873&type=multipage&contentSet=LTO&version=1.0

[4] Morning Chronicle, July 24 1827.

[5] Anonymous, Standard Court of Chancery, June 21 1831, Issue 1280, http://find.gale.com/dvnw/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=DVNW&userGroupName=wschool&tabID=T003&docPage=article&docId=R3211867340&type=multipage&contentSet=LTO&version=1.0

[6] Standard, June 21 1831.