Article by Elizabeth Wells, Archivist, first published in College Newsletter, 2013

2013 marks the 60th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation in Westminster Abbey. This would seem to perfect occasion to take a look at the role played by Scholars in coronation services.

The privilege of being the first commoners to acclaim each new sovereign at their coronation in Westminster Abbey is reserved for the Scholars of Westminster School. At a coronation, when the crown touches the Monarch’s head, it is the Scholars who hail the King or Queen thrice in chorus with the words ‘Vivat Rex’ (or ‘Regina’). Their role in the ceremony has long led to coronations being an anticipated occasion, with one O.W. noting that ‘his sole source of satisfaction at leaving school was the knowledge that he should no longer wish for the death of his sovereign, as till then he had been completely possessed by the ambition of witnessing a coronation as a Westminster boy’.

Although it is probable that Scholars were present at every Coronation since the refoundation of the School by Queen Elizabeth, the first reference to their presence occurs in Sandford’s History of the Coronation of King James II. It is noted that ‘when the Queen entered the Choir, the King’s Scholars of Westminster School, in number forty, all in surplices, being placed in a Gallery adjoining the Great Organ-Loft, entertained Her Majesty with this short Prayer or Salutation, ‘Vivat Regina Maria’; which they continued to sing until His Majesty entered the Choir, whom they entertained in like manner with this Prayer or Salutation ‘Vivat Jacobus Rex’, which they continued to sing until His Majesty ascended the Theatre.’ From this coronation onwards there are records of scholars being in attendance at coronations in Westminster Abbey.

Although it is probable that Scholars were present at every Coronation since the refoundation of the School by Queen Elizabeth, the first reference to their presence occurs in Sandford’s History of the Coronation of King James II. It is noted that ‘when the Queen entered the Choir, the King’s Scholars of Westminster School, in number forty, all in surplices, being placed in a Gallery adjoining the Great Organ-Loft, entertained Her Majesty with this short Prayer or Salutation, ‘Vivat Regina Maria’; which they continued to sing until His Majesty entered the Choir, whom they entertained in like manner with this Prayer or Salutation ‘Vivat Jacobus Rex’, which they continued to sing until His Majesty ascended the Theatre.’ From this coronation onwards there are records of scholars being in attendance at coronations in Westminster Abbey.

The long reign of Victoria, and poor recording of the procedures followed for her 1838 coronation, resulted in the school having some difficulty asserting the rights of the scholars. Before the coronation of Edward VII, Dr. Gow, Head Master, attended the Court of Claims to support the right of the King’s Scholars to be present and acclaim the King, using precedents drawn from the Abbey’s Muniments. Dr. Gow noted afterwards that ‘the Court was in doubt whether the shouts of the boys constituted a service of which the Court should take cognizance, but Lord Halsbury expressly said to me “We are agreed that you ought to be there” and the other members of the Court assented with smiles’.

Dr. Gow anticipated that there might be changes to the coronation ceremony in 1902, noting that whilst the Abbey ‘remains the same size as before…the British Empire has nearly trebled its population and has developed an extraordinary taste for pageantries’. As a result the King’s Scholars, for the first time since 1685, were placed in the Triforium, where they have sat for coronations ever since.

However, one aspect of the 1902 coronation was to prove beneficial to the Scholars. In the first part of the service the Sovereign processes from the west end of the Abbey through the nave and choir to the Theatre. During this verses from Psalm 122 are sung: ‘I was glad when they said unto me: We will go into the house of the Lord’. Several musical settings of these words had been used over the centuries, but Sir Hubert Parry’s version has been sung since its first performance at the coronation of Edward VII in 1902. Parry incorporated into his setting the cries of ‘Vivat Rex! and Vivat Regina!’ thus acknowledging the part played by the Scholars in the service.

Their role was further confirmed when in 1907, Sir William Anson wrote his influential The Law and Custom of the Constitution. In this text Anson noted that at the coronation ‘the people signify their willingness and joy by loud and repeated acclamations’ and for this purpose are ‘represented by the boys of Westminster School, who rehearse beforehand the part played by the crowd at a medieval coronation’.

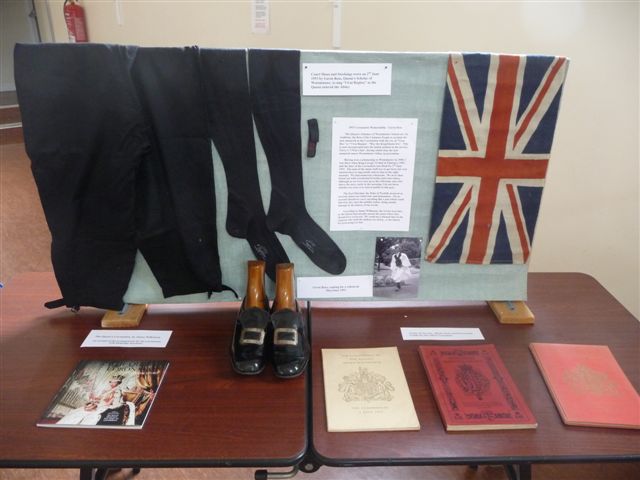

The costume of the scholars appears not to have been fixed and we have few detailed accounts of what was worn. We do know that for the coronation of George VI and Queen Elizabeth in 1937 the scholars wore ‘a swallow-tail coat, white waistcoat, dress shirt, butterfly-collar and bands, velvet knee-breeches, silk stockings, patent-leather slippers with buckles, open surplice, and college-cap. The Master of the King’s Scholars noted that this was acquired cheaply from the School Store and the whole cost was under £2. He also had the foresight to have some food sent up to the Triforium in advance, rather than risk the scholars having ‘bulging pockets’ and College Hall obliged by providing biscuits and chocolate.

The Coronation of our present Queen was, given the post-war climate, an austerity occasion. The Coronation Banquet was held in the bombed-out remains of School, where a temporary roof had been erected and tapestries brought through to help cover the ruined walls. It also has the dubious honour of being the first venue in which the newly created Coronation chicken was served.

On the fiftieth anniversary of the Coronation, Queen’s Scholar the Rt. Rev. John Oliver recalled ‘because we were positioned so high in the Abbey, we had room to move around to get a better view. I knew as the crown was placed on the Queen’s head that it was a dramatic moment I would remember for the rest of my life. She was beautiful and impressive and the whole thing was just amazing’.

Finally, it should be noted that Coronation relics are not exempt for the habit of Westminster boys to inscribe their names on anything which remains still long enough. The tapestry which now hangs in the Jerusalem Chamber, used at the coronation of James II, bears the marks of Westminster Scholars. There are also many names identifiable on the Coronation Chair, currently undergoing restoration, and its double, made for the joint coronation of 1688. King’s Scholar Thomas Strange’s name is clearly visible, neatly cut on the seat of Queen Mary’s Coronation Chair.