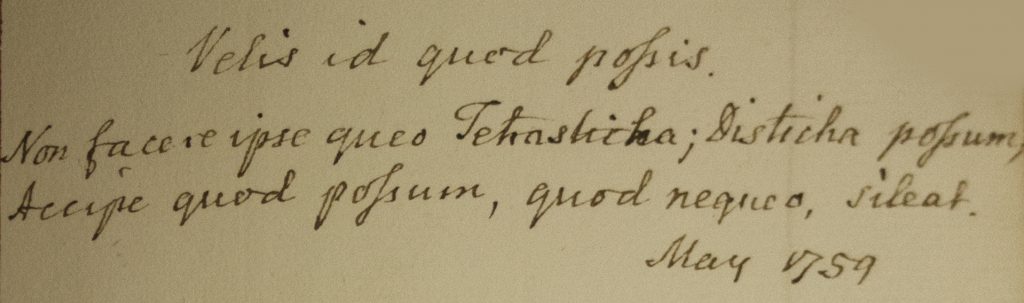

Non facere ipse queo Tetrasticha; disticha possum,

Accipe quod possum, quod nequeo, sileat.

Jeremy Bentham, May 1759

Cut your coat according to your cloth

A quatrain isn’t something I can do;

But here’s a couplet: Take what’s offered you.

Translation by Nicholas Stone, 2015

Last school year Jeremy Bentham (OW 1755-1760) was celebrated as our new airy space off School was christened in his honour as the Bentham Room.

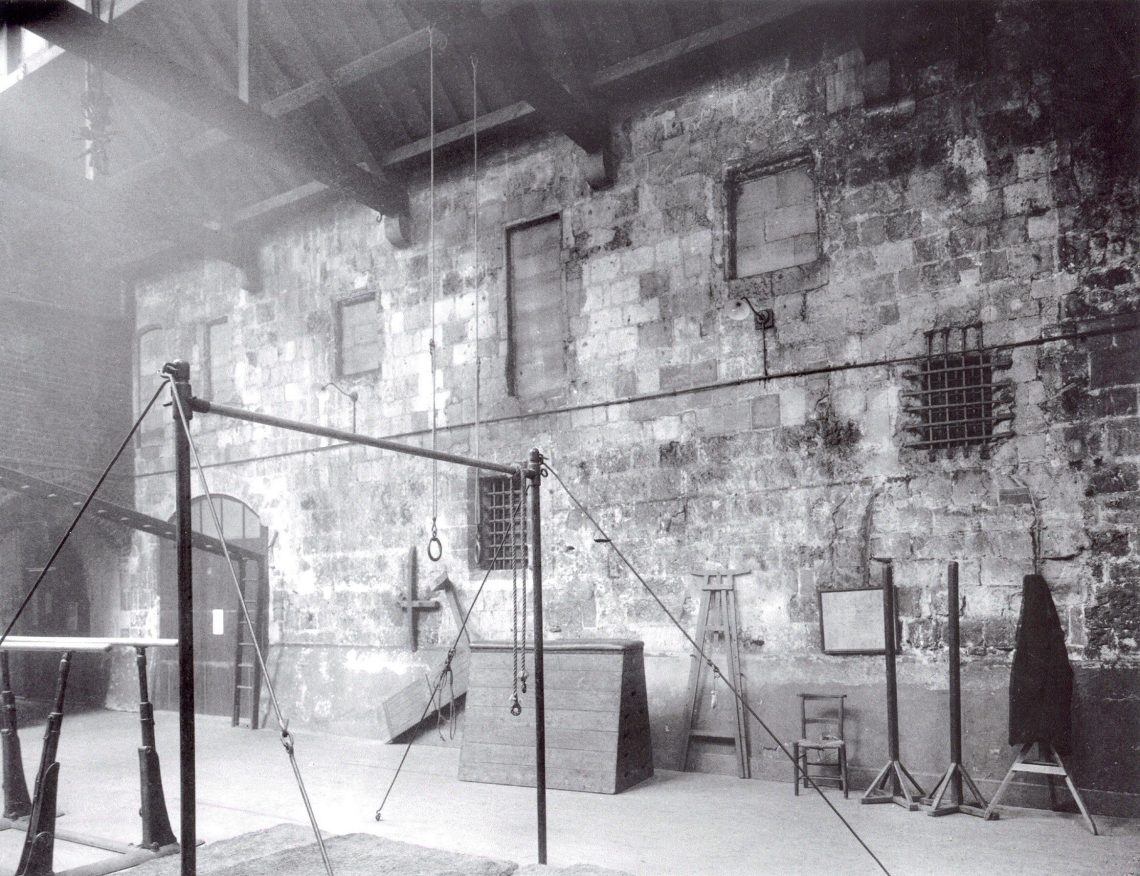

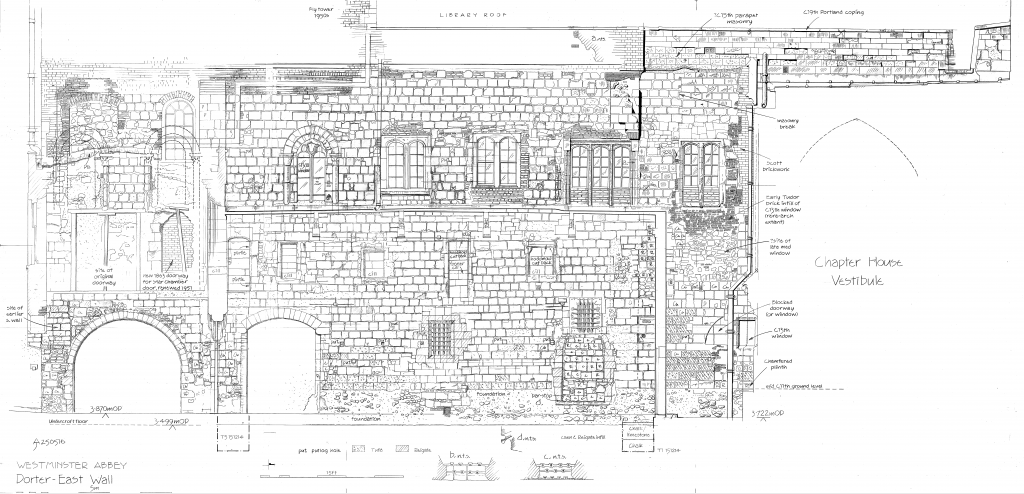

Whilst the room is our latest addition, it has been created from the shell of the school’s 19th century gymnasium, constructed in 1861 by Sir George Gilbert Scott, the famed architect of St. Pancras and the Albert Memorial. The site was given to the school by the Abbey for a covered play area, as the pupils were running amok in the cloisters on rainy days. It consisted of a small patch of land at the foot of the former monastic dormitory, parts of which date back to the 10th century. The area had originally been the monks’ graveyard so it was not possible to create deep foundations for the new building. The awkward shape of the space necessitated the gym’s curved north wall which allows room for a flying buttress of the Abbey’s Chapter House.

150 years later the gym was no longer required for its original purpose after the school purchased a 999-year lease for the Royal Horticultural Society’s Lawrence Hall. This became the school’s sports centre, and whilst the square-footage of the gym was still very much needed, particularly during exam season, the building was clearly ripe for renovation. Ptolemy Dean’s creative design inserted a mezzanine floor that allows the room to be accessed from School via the Markham Room, whilst a secret exit to behind the stage makes it an ideal green room for performances. The former entrance, through the Dark Cloister, is still used to a storage area beneath, although the old staircase hidden underneath a trap-door in the Markham room has been lost.

The refurbishment needed to take place quickly as the space is now essential for the summer examination season. This prevented any serious structural alterations and the existing roof was renewed rather than replaced, with lead-flashing crafted on site. New windows were inserted giving views of the Houses of Parliament and the soaring spires of the Chapter House. Earlier apertures, now filled in with stone, are visible on the west wall, adjoining School and the Abbey Library. These are remnants from when the building was the monk’s dormitory and private cells were haphazardly built out from the communal ‘dorter’. Scott’s magnificent oak beams can now be viewed more closely crossing the room, adorned with hooks which originally supported ropes, hanging bars and other gymnastic equipment.

Unfortunately, the school does not have a portrait of Jeremy Bentham in its collection to adorn the room. We therefore decided to display pictures that mark another time of renewal in the school’s history – the post-war period. School was amongst the school buildings seriously damaged by war time bombings and the last to be rebuilt; it was not formally reopened until the visit by Her Majesty the Queen to mark the school’s 400th anniversary in 1960. The incendiary bomb that hit in May 1941 completed destroyed the wonderful oak hammer-beam roof that had spanned the hall, along with the ornate Tudor ceiling and original star-chamber door once visible in the Markham Room. The phoenix which is now visible on the fly-tower of School commemorates the transformed buildings rising from the ashes of this destruction.

A painting by John Croft (OW 1936-1939), recently acquired with the assistance of the artist, was selected to hang in the Bentham Room. Croft worked as a code-breaker during the war at Bletchley Park and Orford House. He returned in 1947 to depict the shell of the bombed College Dormitory building, prior to its refurbishment. He continued to paint alongside pursuing a career in the civil service and following his retirement is able to focus exclusively on his art. A number of portraits of pupils painted in the 1950s also hang in the room. Amongst them is a picture of Tom Meade (OW 1949-1953) who was one of the Scholars invited to the Coronation of Elizabeth II in Westminster Abbey in 1953. The banquet following the ceremony took place up School, surrounded by its crumbling walls, hastily masked by tapestries, and under the cover of a temporary corrugated iron roof.

Bentham came to Westminster long before the gym was constructed, but he would have known School well as the site of his daily lessons. He was admitted at the young age of seven, but clearly excelled academically beyond all expectations. Bentham was elected as a King’s Scholar in 1759, but chose to remain a Town Boy for his short remaining time at the school. At the age of twelve he left for Queen’s College Oxford, taking his degree three years later. His writings contain the earliest recorded mention of the Pancake Greaze and whilst he was dismissive of the school, describing it as ‘a wretched place for instruction’, his education clearly had a considerable impact upon him. There is still much to be discovered of his work and University College, London (UCL) is conducting a project ‘Transcribe Bentham’ which enables volunteers to transcribe his digitised manuscripts. By crowd-sourcing in this way an endeavour that would have taken decades to complete will be finished in a few years.

At Westminster we do have some relics of Bentham’s time at the school, though nothing quite as striking as the ‘auto-icon’, his preserved corpse which is on display at UCL in a glass box. In our collection are two commonplace books in which he copied essays and poetry written whilst a pupil at the school. Nicholas Stone (OW 2011-2016) has translated the poems from their original Latin and Greek and published several in The Camden in 2016. The thesis Velis id quod possis could be literally translated as ‘Want what you can have’ and is drawn from Terence’s Andria. Lines from these classical works were used to inspire pupils to generate their own verses in Latin or Greek from Elizabeth I’s reign onwards. Necessity is, of course, the mother of invention, and the Bentham Room, an innovative solution to a difficult space, perfectly encapsulates Bentham’s couplet.

For more information about the school’s old gym read Tom Edlin’s article ‘150 Years of the Gym: 1861–2012’ in The Elizabethan, 2012. A chapter on Jeremy Bentham by A.C. Grayling can be found in Loyal Dissent: Brief Lives from Westminster School edited by Head Master Patrick Derham. A longer article containing Nicholas Stone’s transcriptions and translations of ‘Jeremy Bentham’s Westminster poems’ can be found in 2016 issue of The Camden. UCL’s ‘Transcribe Bentham’ project continues with almost 18,000 manuscript pages transcribed or partially transcribed. To read more about the initiative or take part visit: http://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/transcribe-bentham/