College Hall is one of the oldest and perhaps most remarkable parts of Westminster School. It has survived over six hundred and fifty years, encompassing different ages, social upheaval and times of both prosperity and hardship at Westminster, to be the place where much of the school eats its breakfast, lunch and dinner today. It is claimed by Westminster Abbey that the hall is the oldest continuously used dining room in London. Furthermore, it has welcomed many famous people and has had many different uses, but is really largely unchanged from how it looked when Abbot Nicholas Litlyngton had it built in the 1370s as his state dining hall for himself, his household and his guests.

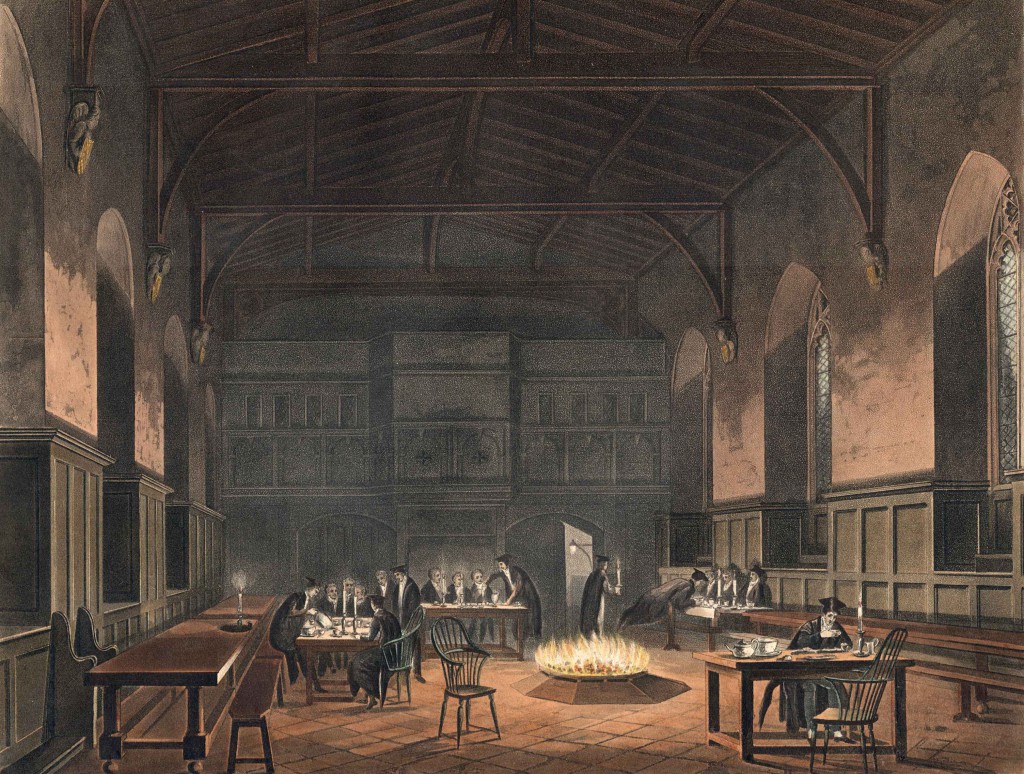

It is widely understood now that the Abbot had the hall built roughly between 1369 and 1376. He would have sat on at the raised dais at the north end of the hall and entered the room from the Deanery through a passage which has now been blocked up. Litlyngton marked it with his coats of arms by painting them on the shields in the hands of the angels supporting the roof, as shown in the picture below: these can still be seen today, along with the shields of Edward the Confessor and the College of St. Peter. John Palterton was the master stone mason who had parts of the cloisters constructed, and, being a well-known glazier, glazed the windows, thus finishing the hall’s construction. The lions and roses of England seen on the back wall were also painted around this time. A central open fire on an octagonal fireplace was constructed for cooking, and was to remain until 1847 when its replacement of a stove arrived. The louvre/lantern above in the centre of the ceiling was installed to let out smoke from the fire, shown in Ackerman’s etching.

It is widely understood now that the Abbot had the hall built roughly between 1369 and 1376. He would have sat on at the raised dais at the north end of the hall and entered the room from the Deanery through a passage which has now been blocked up. Litlyngton marked it with his coats of arms by painting them on the shields in the hands of the angels supporting the roof, as shown in the picture below: these can still be seen today, along with the shields of Edward the Confessor and the College of St. Peter. John Palterton was the master stone mason who had parts of the cloisters constructed, and, being a well-known glazier, glazed the windows, thus finishing the hall’s construction. The lions and roses of England seen on the back wall were also painted around this time. A central open fire on an octagonal fireplace was constructed for cooking, and was to remain until 1847 when its replacement of a stove arrived. The louvre/lantern above in the centre of the ceiling was installed to let out smoke from the fire, shown in Ackerman’s etching.

College Hall has been home to so many interesting little parts of history because of its location right in the centre of Westminster. One of the Hall’s claims to fame was that Edward IV’s queen, Elizabeth Woodville, found sanctuary there during the Wars of the Roses with her son Prince Richard. Although Richard, as second in line to the throne, was possibly murdered in the Tower of London, Elizabeth lived on until 1492. After the execution of Charles I, the King’s body was laid upon a table in the Dean’s Great Kitchen, which leads us to assume that it was brought to the kitchens on the south side of the hall.

Following the re-founding of the school by Queen Elizabeth I, the Hall was one of the new privileges given to the Queen’s Scholars, who were allowed to take their meals there with the Dean and Chapter. The Dean and Chapter kept the use of the Hall has a dining area until the 1730s. They would eat in the style of an Oxford or Cambridge college; other privileges the Foundress and Dean Bill granted were the school dress with an outer coat for the winter and forty beds with blankets.

Interactions between the diners often came to blows, however: the Chapter Book of 1555 records that it was found necessary to create a rule that there would be a fine of one shilling ‘if anye of the pety canons scolemasters or any other of the clarkes or otherwise in the comones [meals] above the adge of xviii yers shall calle any of those before namyed in their communes foole knave or any other contumelius [insolent] or slanderus worde’.

Another moment in ‘Colledge’ Hall’s history which witnessed violence was also recorded by the Chapter Book in this year. There is a note that ‘whereas ser hamonde pryste dyd breake John Wodes heade beinge one of the clarkes wt [with] a pote he was comandyd to ye [the] gate-house for the space of iii dayes by Mr. deanes comandement and payde Ion [John] wode [Wode] for the healinge of his heade xls [40 shillings] by the decree of Mr. deane and the chapiter’.

In his Westminster School: A History, Lawrence E. Tanner writes that that the Scholars of this time would eat to the accompaniment of Bible readings, and that on every Wednesday they were served meat, on the condition of giving 6s. 8d. to the parish’s poor, at the instruction of the Archbishop of Canterbury Matthew Parker. The fire in the Hall was also the focus of a challenge for Junior King’s/Queen’s Scholars for many years: the boys would try to jump over the fire as it blazed away. All told, the keeping of a fire there continued for a remarkably long time and was almost certainly the last of its kind left in the country.

In his Westminster School: A History, Lawrence E. Tanner writes that that the Scholars of this time would eat to the accompaniment of Bible readings, and that on every Wednesday they were served meat, on the condition of giving 6s. 8d. to the parish’s poor, at the instruction of the Archbishop of Canterbury Matthew Parker. The fire in the Hall was also the focus of a challenge for Junior King’s/Queen’s Scholars for many years: the boys would try to jump over the fire as it blazed away. All told, the keeping of a fire there continued for a remarkably long time and was almost certainly the last of its kind left in the country.

Perhaps, however, the issue which has caused most interest and debate in College Hall are its tables and benches. It has often been claimed that the furniture which now stands in College Hall was constructed from the wood from the wrecks of the Spanish Armada, having been given to the school by Queen Elizabeth following their capture. Unfortunately, close examination of the tables has since disproved this. The tables are a mixture of elm and fast-growing oak, and although these woods cannot be used to date the tables precisely, there are indications that some of the furniture dates from the fifteenth century.

Fast-growing oak is generally found in furniture from the medieval or early modern times, and the oak was probably local because around this time, the cost of transporting felled oak doubled with every additional ten miles travelled. The oak is also likely to have come from the Abbey estates, because in order to grow quickly it would have to be planted on well-managed lands. The tables are probably not Armada wood; ships’ timbers were very rarely recycled into other furniture as contemporary carpenters found seasoned wood difficult to carve. The benches and tables have characteristics that suggest that the wood was green when it was cut and assembled: green wood was favoured by carpenters in that period because it was simpler with which to work.

College Hall is also where Westminster’s Latin Play was performed between 1560 and what is likely to have been the middle of the seventeenth century: certainly by 1704, the play’s ‘revival’, it had moved to the King’s Scholars’ old dormitory in modern-day Dean’s Yard. Whenever the Play was performed often the Hall would be lit up by torches and strewn with rushes for effect. This school tradition is most likely to have been staged on the floor of the Hall underneath the Musician’s Gallery at the south end of the hall, which also dates from the time of Elizabeth I. The play was performed almost every year in Queen Elizabeth’s day, save for when the school had fled to Putney and Chiswick for fear of the plague. Scenery was used, as can be identified from the Abbey’s muniments, which record orders that the school placed for such props. No expense was spared in the hiring of costume, which was hired from the Office of the Revels in Clerkenwell and brought by boat to Westminster. The Queen, amongst many Elizabethan nobles, attended the plays there frequently, with plays that she certainly attended include 1565’s performances of Miles Gloriosus and the Sapientia Solomnis. In the play’s later years, some of the most prominent personages of the country were present: in 1927 the Prime Minister, the Speaker of the House of Commons, two former Lord Chancellors, many MPs and others besides came.

During the Dissolution of the Monasteries, an inventory of College Hall was taken which revealed some interesting contents. These included ‘a grete olde arres [wall-hanging] at the hye dease [‘top’ table]’, ‘ii bankers [cushion-covers] of tapestry’, ‘ii hangingis for the syde of the hall in grene saye’, ‘a great Joyned Chare for the Quenys [Catherine of Aragon’s] coronacyon’, ‘an olde grene banker the Arrasys [wall-hangings] in the hall and in the parlour and a fest[i]val in Printe [a book]’. These tapestries were taken down in 1733 when the wainscoting, or wooden panelling on the lower parts of the walls, was put in place. Changes to the hall’s decoration did not stop here, however. The Abbey’s muniments record that in 1749 the hall was further ‘beautified and adorned’ by entirely new paving the same with Swedes and Danes marble laid arrasway [the lozenges of Swedish and Danish marble]’.

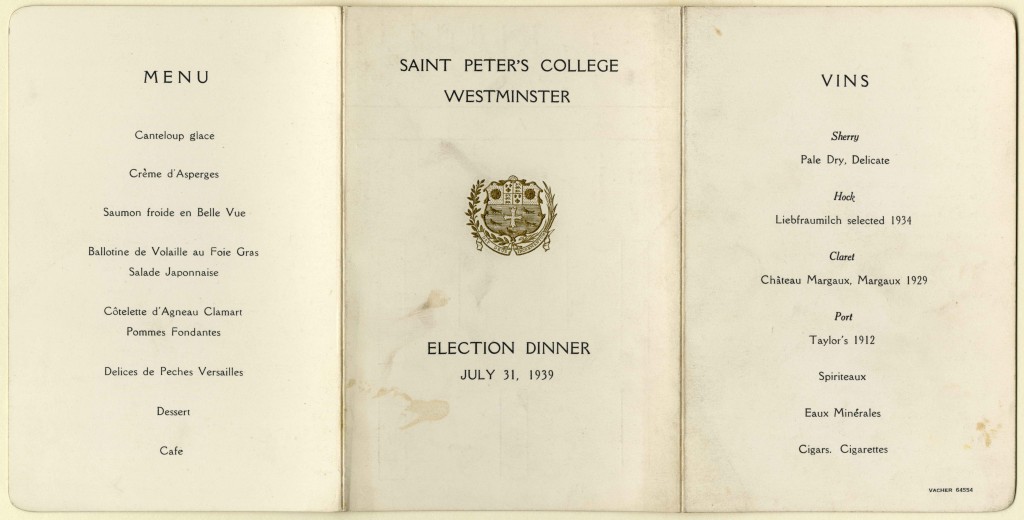

A longstanding Westminster tradition that takes place up College Hall is the Election Dinner. The dinner is held by the Head Master once a year and some pupils who are leaving the school, teachers, a number of Old Westminsters and the Master of Trinity College, Cambridge and the Dean of Christ Church, Oxford are invited. Until 1857, invitations to the election dinner were confined to the Scholars, but since then Old Westminsters have been invited as well. Historically, the purpose of the dinner was to celebrate the ‘election’ of the scholars; that is, the ‘major’ scholars (Queen’s Scholars who are leaving the school) being chosen to join either Trinity College, Cambridge or Christ Church, Oxford. The practice of electing the ‘major’ scholars in this way ceased by the 20th century.

The Election Dinner has roots that could be viewed to stretch back to the 1580s as we have records of epigrams recited by Queen’s Scholars from this time. After the attendees have eaten, the epigrams are recited by pupils, and historically music was played. In the Muniment Room of the Abbey we have records of the expenses of the dinner: we know that lute strings were bought for ‘ye violls’ and in 1620 the school paid for ‘the carriage of a winde instrument into the Colledge Hall and for the tuneinge the same against the Election’. Beyond telling us about the music that was played, we also know how the Electors, the Dean of Christ Church and the Master of Trinity, travelled to the Dinner: in 1573, the cost of ‘vij horses grasse for iiij dayes’ and ‘ij trusses of hay for one gelding xvjd’ had to be accounted for.

Unlike during the two World Wars, the Election Dinner continued to be held during the Commonwealth and the English Civil War. The food continued to be unusual and extravagant too, for instance ‘oranges and lemmons’, ‘sammon and lobsters’, asparagus, ‘a gallon of sack’ and a ‘gallon and a quart of claret’ were all consumed during these uncertain times, according to the Westminster Abbey Muniments. In the 1930s, however, the trends of the time dictated the menu more closely: every dinner began with melon glacé, and had a main course of roast veal. In the 1990s, however duck and lamb took centre stage next to salmon terrine and the menus became more exciting, taking the form of a brochure folded thrice. Nowadays, desserts are often chocolate: the Election Dinners of 2005, 2006 and 2013 served chocolate truffle, chocolate parfait and chocolate torte respectively. For as far back as we have records, petits fours have been eaten after the meal as they are intended to accompany the epigrams afterwards.

Unlike during the two World Wars, the Election Dinner continued to be held during the Commonwealth and the English Civil War. The food continued to be unusual and extravagant too, for instance ‘oranges and lemmons’, ‘sammon and lobsters’, asparagus, ‘a gallon of sack’ and a ‘gallon and a quart of claret’ were all consumed during these uncertain times, according to the Westminster Abbey Muniments. In the 1930s, however, the trends of the time dictated the menu more closely: every dinner began with melon glacé, and had a main course of roast veal. In the 1990s, however duck and lamb took centre stage next to salmon terrine and the menus became more exciting, taking the form of a brochure folded thrice. Nowadays, desserts are often chocolate: the Election Dinners of 2005, 2006 and 2013 served chocolate truffle, chocolate parfait and chocolate torte respectively. For as far back as we have records, petits fours have been eaten after the meal as they are intended to accompany the epigrams afterwards.

Since 1870, day pupils at Westminster have eaten lunch in College Hall. College Hall was refurbished in the 1970s thanks to the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths and the Pilgrim Trust. It is safe to say that College Hall has changed little over the last several hundred years. It is little things like these, and many that have not been recorded, that make College Hall a place so close to Westminster School.