CECIL GRAHAM. What is a cynic?

LORD DARLINGTON. A man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.

CECIL GRAHAM. And a sentimentalist, my dear Darlington, is a man who sees an absurd value in everything, and doesn’t know the market price of any single thing.

Oscar Wilde, Lady Windermere’s Fan

Around 2 years ago I visited a classics class with a selection of rare books from the school’s collection. It was during this lesson that I was first asked questions which I now encounter on an almost weekly basis: ‘how much would this have cost?’, ‘how much is this worth now?’, ‘what is the most valuable item in the school’s collections?’

At first I found it all too easy to be dismissive of these sort of questions, but the sheer frequency with which the subject is raised has forced me to address my own prejudices. Why is it so difficult to talk about value and worth?

The best things in life are free…

I have yet to meet an Archivist who entered the profession for the cash, but to ignore the role that money plays in our society is dangerously naïve. Debrett’s Guide to Etiquette states that ‘money is the oil that greases the wheels of society but oil is filthy sticky stuff and we should clean our hands of it before coming out in polite society’. However, it also acknowledges that ‘at dinner parties across the country, civilised people are comparing their house prices, marvelling at the cost of each other’s cars and revealing their bonuses and salaries’.

When pupils began to ask me about prices, I initially wrote off their questions as purely mercenary. I now realise that in the majority of cases this is an unfair accusation. Whether we like it or not, many people understand the world through the lens of money. Knowing how much something cost when it was first bought and its current market price can help us understand the individual who purchased it and how society has changed. Together these figures raise interesting questions on the subject of what we mean by value.

I’ve seen the future, I can’t afford it…

Part of my ambivalence on the subject of value is that it is very difficult to compare what things cost in the past to what they cost today. The famous scene in the ‘Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery’ when Dr. Evil, having been cryogenically frozen for 30 years, attempts to hold the world to ransom for the then laughably small sum of ‘one million dollars’ hints at the problem. Prices can change drastically even over short periods of time. I can easily tell a class what a 16th century Latin grammar book cost in pounds, shillings and pence but to most people this answer is meaningless. As a result we often hear television historians confidently declaring that something which cost £X then would cost £Y now. Of course these sorts of comparisons can help our understanding, but how are these figures derived?

The excellent website ‘MeasuringWorth.com’ provides various calculators to convert historic prices to modern equivalents for comparison. It also comes with a helpful analysis of the many different ways these calculations can be conducted, pointing out some of the difficulties in interpreting the results. What better case study than the fees of Westminster School? We are often told that fee paying schools have become less affordable. Do the figures support this supposition?

Using the website’s calculators the £498 annual fees charged in 1966 could equate to anything from £5,511 to £12,730 in the year 2000 depending on which measure is used. The lower figure is derived by looking at the relative cost of goods and services over time and uses the Retail Prices Index. The higher figure takes into account ‘Economic Power’, the amount of income or wealth relative to the total output of the economy and uses Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in its calculation. In total MeasuringWorth offers nine different estimates employing a variety of data including wage indexes, average income statistics and GDP per capita.

Selecting the correct measure largely depends on how we classify the expenditure in the first place. Are school fees a commodity? They certainly fit the description – ‘a good or service, usually purchased by a consumer’, but could they perhaps be classed as a project? – ‘A business or government investment’? I am sure that many parents feel that they are making an investment in their child’s future by sending them to a public school. The fees are also dependent upon income, both in terms of what parents (the customers) are able to pay and as one of the main items of school expenditure is staff salaries. As you can see, there is no straightforward answer.

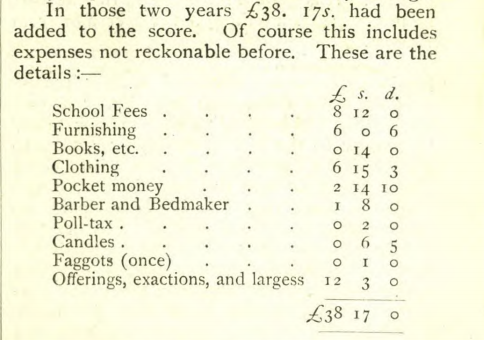

As we try to stretch our comparisons further into the past, things get harder. Francis Lynn, a pupil at Westminster School from 1681-1691, kept detailed accounts of his expenses, but there is no annual or termly fee to be gleaned from his notes. Instead Lynn was responsible for a whole variety of charges, for example:

- 7s to entertain his fellow King’s Scholars when elected to College

- £1 1s 6d for Dr. Busby for three months tuition

- 4s 7d for a Bible, ‘Practice of Piety’ and a comb

- 5d for candles

- 10s 9d for a New Year’s gift to the Undermaster, Dr. Knipe.

When added together for the full 10 years he spent at the school these charges come to £213, an average of just over £15 per year. This annual cost could be calculated as anything between £2,160 and £351,700 in today’s money. There are also crucial changes to our society which need to enter into the equation. In just the last 50 years the way that Britons have used their disposable income has altered rapidly. According to the Office of National Statistics, the price of keeping a roof over your head increased from consuming 8.7% of individual income in 1957 to 21% in 2012, whilst food has shrunk from 33.4% (1957) to 15% (2006) and continues to drop. As we’ve grown wealthier in absolute terms our spending on food has increased subtly, but as a proportion it has fallen massively.¹ There are also a far greater proportion of families accustomed to a dual income than there were in 1957. Finally, we should take into account the increasingly global society we live in, which means that a school such as Westminster now appeals to an international market.

Perhaps it is these changes that limit the use of these comparisons. We know that Dr Busby spent £2 on a Bible in 1656. Would it be more helpful to consider this expenditure in light of his income and other expenses rather than attempting to find a modern equivalent? After all, the 21st century Dr Busby may well have had a kindle.

There is nothing quite as beautiful as cash…

Whilst most of the rare books, works of art and artefacts that make up the school’s collections would originally have had purchase prices, estimating their current market value is a very inexact art. What gives these items value is rarely the raw materials from which they are made. This George III Guinea, made in 1775 from eight grams of twenty-two carat gold, is worth considerably more in its current form to a coin dealer than it would be melted down by a gold merchant.

Market value depends on so many subtle qualities: condition, rarity, provenance and even fashion. John Dryden (OW and Poet Laureate) is no longer as critically respected as he once was and as a consequence rare editions of his work have decreased in monetary value. Andrew Lloyd Webber (OW), a lover of the pre-Raphaelite movement, managed to buy many paintings during his early career when this work was considered passé. Knowing an item’s provenance (its source and previous owners) is vital as proof of authenticity. A painting bought at a Los Angeles auction house for just over £1,000 became worth over £500,000 once identified as from the hand of Thomas Gainsborough. A replica of a Rembrandt painting, even if it is exact in every detail, will only ever be worth a fraction of the original.²

Having said this, as artworks and rare books are often bought and sold at auction their value also comes down to a single blunt measure – the upper-most price of what two individuals are prepared to pay. This leaves our cultural heritage subject to the same speculation as any other commodity, hence the sale, last November, of a Francis Bacon triptych for $142 million. These sort of paintings, along with London’s properties, have become empty vessels in which the world’s one percent hoard their wealth.

This is where Wilde’s distinction between value and price comes into play. Our 16th century portrait of Elizabeth I is worth a fraction of a Francis Bacon painting, but to Westminster School the former is clearly of greater value. One of my favourite items from our collections is the pancake caught by R. S. Milde in the 1922 Greaze. It is utterly worthless – but to us it is priceless.

Keep your hands off my stack…

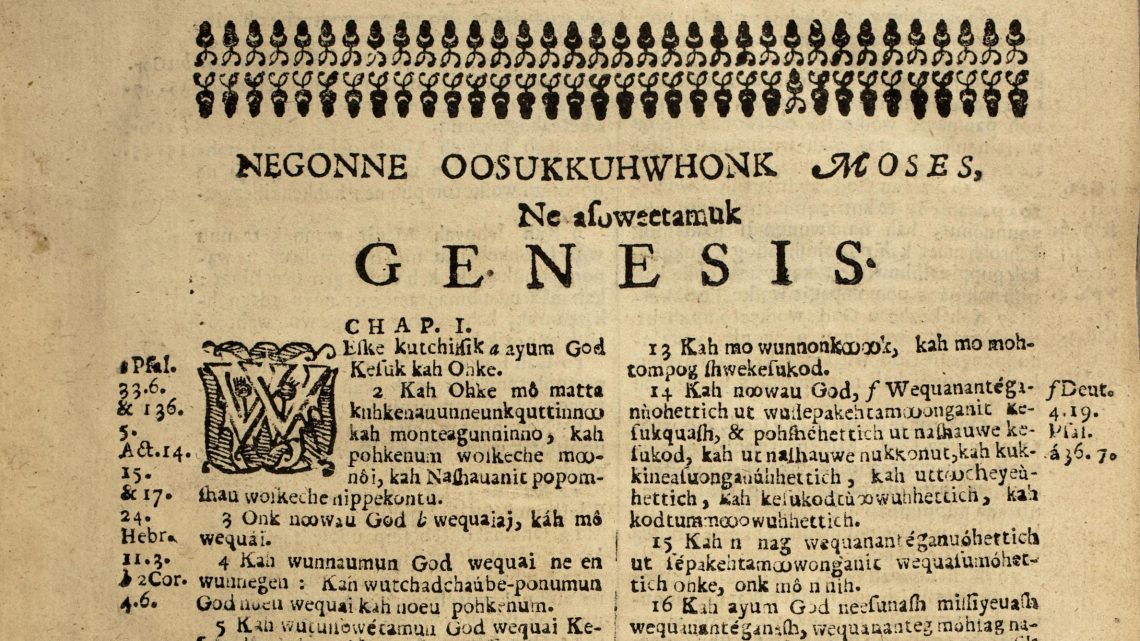

Talking about these items as commodities raises the inevitable question – should they be sold? Could the money their sale would raise be put to better use? This question has been asked at various points in the school’s history with differing results. In the 1960s and 1970s, when Westminster was struggling financially two treasures were sold – a significant collection of Greek, Roman and Anglo-Saxon coins and Dr Busby’s Eliot Bible. These sales are deeply regretted, but they secured the future of the school at a difficult point in its history.

The climate of opinion has changed drastically in the last 40 years. When Tower Hamlets Council suggested that it would sell its Henry Moore sculpture ‘Draped Seated Woman’ in 2012 to help cover the swingeing cuts it was facing there was a public outcry. The reality is that market prices can never reflect the value of our heritage. Selling these assets can be a short-sighted policy, not least because it may put off future donors.

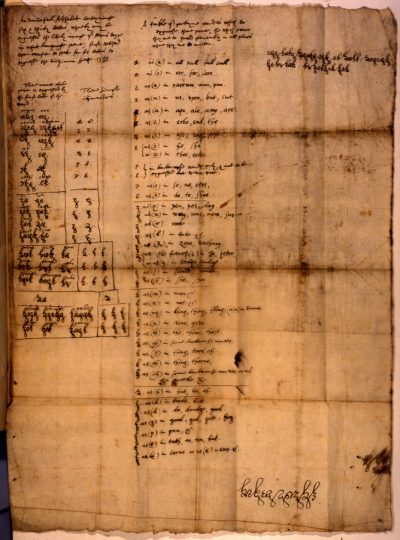

Many of our collections have integrity as a whole and the loss of a single part leaves an ugly scar. Busby’s Eliot Bible, the first Bible printed in the language of a Native American people, the Algonquins, was an important part of his library. An academic has recently conducted research into its natural partner, which remains in the school’s possession: a single page of manuscript in Busby’s papers written by Thomas Harriot. The manuscript is an attempt at writing a phonetic alphabet of the Algonquin language and may well have been derived by Harriot through collaboration with a member of the Algonquin tribe. Together these two pieces told an important story of the relations between the people of 17th Century London and East Coast America. It is very sad that they are now apart.

I think it helps if we view the School not as an owner, but as a custodian. It is our responsibility to safeguard these wonderful items, which were often donated to the school, for future generations. What is more, it is vital that these collections are used as they were intended, to support education, not just within the school community, but for the wider public. It is worth remembering that items which are sold often disappear into private ownership, in distant countries where they are no longer available for research and public edification.

¹ As an aside – this was first observed by Ernst Engel in the 19th Century and the ‘Engel coefficient’ is still used as a reflection of the living standard of a country. See this report from Washington State University for example: wsm.wsu.edu/researcher/WSMaug11_billions.pdf

² Some forgers have gained considerable fame in their own right. The forgeries of Elmyr de Hory, the subject of the film F for Fake directed by Orson Welles, have become so valuable that forged de Horys have appeared on the market.

HEADER IMAGE: Dr Busby’s Eliot Bible in Algonquin

Article by Elizabeth Wells, Archivist, first published in The Camden, 2014