One of the most enjoyable aspects of my work as School Archivist is learning about some of the fascinating events in the lives of Old Westminsters. In 2016, thanks to Ian Petherick (HB 1941-1946), I found out about the incredible journey of the Almond brothers (Basil, David and Francis) from India to the school, then out in Herefordshire, during the Second World War.

In 1940, the three boys and their sister had moved out to India to join their mother and father – Sir James Almond had been made Judicial Commissioner of the North West Frontier Province of India in 1937. By 1942 Lady May Victoria Almond was becoming concerned with her sons’ schooling. The couple decided that she should return to England with the children for, although the journey would be hazardous, India was looking increasingly vulnerable in the face of the Japanese advance through Burma. The family boarded SS City of Cairo in Bombay and, after a few days break at Cape Town, set sail on the morning of 1st November 1942 for Recife, on the Brazilian coast. Their ship was too slow to travel in a convoy, but was to take a zig-zag route across nearly 4,000 miles of the South Atlantic to avoid the attention of German U-boats. There were just over 300 people on board.

On the evening of 6th November, just after the children on board had been sent to bed, a German U-boat commanded by Captain Merten spotted the ship and fired a torpedo into its starboard side. The lights on board failed and the ship began to sink. Lady May, wearing her evening dress, hurried down to the family’s cabins in the dark, collecting her children and ensuring that they all had their life jackets on over their pyjamas. On arriving at their life-boat station they discovered that their allocated boat, No. 2, had already been launched and in the hurry had been damaged and capsized. She finally managed to find a life-boat which had room for her family – Boat 3 of an original 8 life-boats, but they had not moved far from the sinking ship when Captain Merten fired a second torpedo. This sent up a column of water and debris which crashed down onto the life-boats, destroying Boat 3 and sucking its passengers under water. When Lady May surfaced she could find three of her children but David, then aged 12, was missing. She made the difficult decision to guide the three children towards one of the remaining life-boats and must have been enormously relieved when they found David a short way out – according to him they were the ones who were lost!

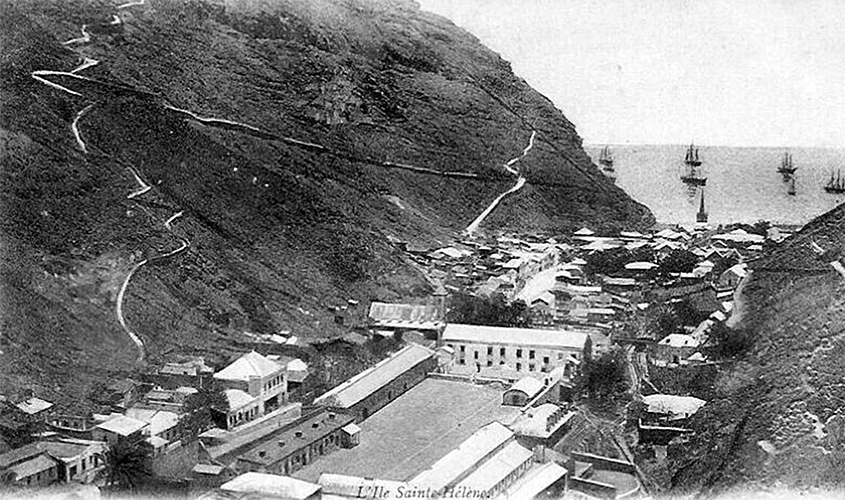

Now only six over-full life-boats remained, many damaged by the blast, and none had room for the whole family. In the end there was no option but to split up with David and Francis in Boat 4 and the rest of the family in Boat 8. It was around this point that the U-boat surfaced. Captain Merten gave them an approximate guide to the direction of nearest land which was the tiny island of St. Helena, 500 miles to the north-east. They were 1,250 miles off the coast of Africa and 2,250 miles off the coast of Brazil. His final words to the group were ‘Goodnight, sorry for sinking you’. He omitted to tell the survivors that he had blocked the SS Cairo’s distress call, fearing that it would guide Allied ships to his position.

At dawn the six remaining life-boats drew together and did a roll count. Miraculously only six men were missing. The group differed over the best course of action. Some wanted to stay where they were, expecting a ship to arrive at any minute in answer of their SOS call. Others thought the only hope of survival was to reach St. Helena – this was a long shot as they had only limited means of navigation. Fresh water was in short supply and calculating that it would take them 21 days to reach land they settled on ration of just over 100ml per person each day – ⅕ of a pint. Although there was plenty of food, it was dry and the survivors were soon too dehydrated to eat much. The boats were over-crowded so there was no space to lie-down or stretch. The sun was fierce during the day whilst at night the temperature dropped and it was difficult to keep warm. They knew there were sharks in the water and did not attempt to catch fish for fear of luring them towards the boats.

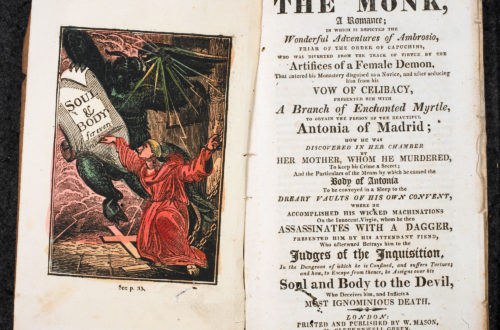

David and Francis became friendly with a young woman named Margaret Gordon whose husband had died in the second torpedo strike. Looking after the boys had helped her manage her grief and so at first the boys stayed with her in Boat 4. However it was not long before strain of keeping the boats together and the subsequent slow progress led arguments to break out amongst the survivors. On the 5th day the Captain decided that Boat 1, the fastest, should strike out alone to get to St. Helena as quickly as possible and send help to the remaining boats. David and Francis rejoined their family in Boat 8. The boys, adhering to the scout’s motto were well prepared. Francis had provided his small pen knife to the crew of Boat 4 and Basil had a lurid ‘thriller’ whose pages were used for an unmentionable purpose – much to the annoyance of some of the other children who wanted to read the book.

The strain of the situation soon began to take its toll on the survivors. On the 4th night an elderly man had stood up to urinate and fallen overboard, being swept past the remaining boats until he was out of reach. Arguments began about the water rations and some began to drink sea water, in spite of the advice of the ships doctor, a man named Quantrill. Several men died as a result of consuming too much salt water. On some days they spotted clouds in the distance and attempted to steer the boat towards the storm with tarpaulin spread out ready to catch the precious rain drops, but they never arrived in time. On the 13th day they calculated that they were still 200 miles from St. Helena with all of the other boats now far from sight. Dr Quantrill, seeing the exhaustion and ill-health of those in the boat began distributing the water ration early when suddenly a ship was spotted on the horizon. The Captain of the ship, Bendoran, nearly sailed past, fearing the life-boat was a decoy for U-boats, but then spotted the children on board. In less than a week the family were back in Cape Town where they had to wait six weeks before nervously boarding the MS Straat Sunda which would return them safely to England.

At around the time that the Almond family on Boat 8 were rescued, Boats 5, 6, and 7, their crews similarly depleted, were approaching St. Helena where they were spotted and brought ashore. Boat 1 which had struck out ahead was not so lucky. Some of those on board had severe injuries from the initial torpedo attack and died, but some seemingly healthy men also died. Half were dead by the 15th day. By the 19th day they began to realise that they might have missed St. Helena. After nearly a month only two men and a woman were left alive, without the strength to row, when it rained. This fresh water enabled them to survive a few more days until they were sighted on day 36 by a German ship – they had travelled 500 miles past St. Helena. The men recovered once on board but the woman required an operation and died as a result. The ship was travelling between Japan and Bordeaux with valuable cargo and was a natural target. On New Year’s Day as it approached the French coast it came under attack. One survivor was sent on a life-boat to the Spanish coast from whence he was able to travel back to England. The other survivor was picked up by a German U-boat and taken to St Nazaire and then interned in a German POW camp until the end of the war.

And what of Boat 4 and the boys’ friend Margaret Gordon? The only woman on the boat, she took it upon herself to look after the other survivors. However, the crew rapidly depleted as once again people were unable to resist the urge to drink sea water. After 17 days they made the decision to abandon hope of finding St. Helena and instead turn west towards the South American coast. After a month only Margaret Gordon and one other survivor, James Whyte remained. On December 27th rain fell on the boat and they were able to collect enough water to stay alive a little longer. They did not realise it, but they were less than 100 miles from the Brazilian coast and were about to be picked up by a naval ship. After having convalesced in a hospital in Recife, James Whyte flew to New York and joined a ship bound for Liverpool. This ship was blown up in the mid-Atlantic by another German U-boat and there were no survivors. Margaret Gordon decided that she would not cross the Atlantic until after the end of the war. She wrote a number of moving letters to the relatives of those with whom she had shared Boat 4. She also kept a promise she had made to Francis Almond and sent him a replacement pen knife – his original was lost with James Whyte.

Out of a total of 311 people aboard City of Cairo, 104 died, including 79 crew members, three gunners and 22 passengers.

Postscript

None of the brothers discussed their difficult journey to school with their fellow pupils. That this story is known is largely down to the journalist Ralph Barker, who published a book on the episode entitled ‘Goodnight, sorry for sinking you’ and organised a reunion of survivors on HMS Belfast. Amongst the guests was Captain Merten, the U-boat captain who had sunk the ship, who was then aged 79.

In 2015, a British led team recovered £34 million of silver coins that had been carried by the ship. The silver rupees were called in by London to help fund the war effort but they never made it to Whitehall’s coffers. The coins have now been melted down in the UK and sold, with the undisclosed sum divided between the treasury – which technically owns the coins – and the salvagers, who take a percentage of the sale.

Post-Postscript

It would appear that I was incorrect in my assertion that the boys did not speak of their traumatic journey. A contemporary wrote, following the publication of this article in The Elizabethan Newsletter in 2016, that ‘I can even now recall the day of [the Almond brothers’] arrival, and the drama of the story they told…when they arrived sunburnt and in odd clothes at Ferney in November 1942…In the dormitory…we heard from David and Francis a great deal of their fraught and dangerous journey, with their mother and sister. No doubt in another dormitory of older boys, Basil was telling them’

HEADER IMAGE: Salvaged coins from the wreck of the SS City of Cario

This article, by Elizabeth Wells, Archivist, was first published in The Elizabethan Newsletter, 2016