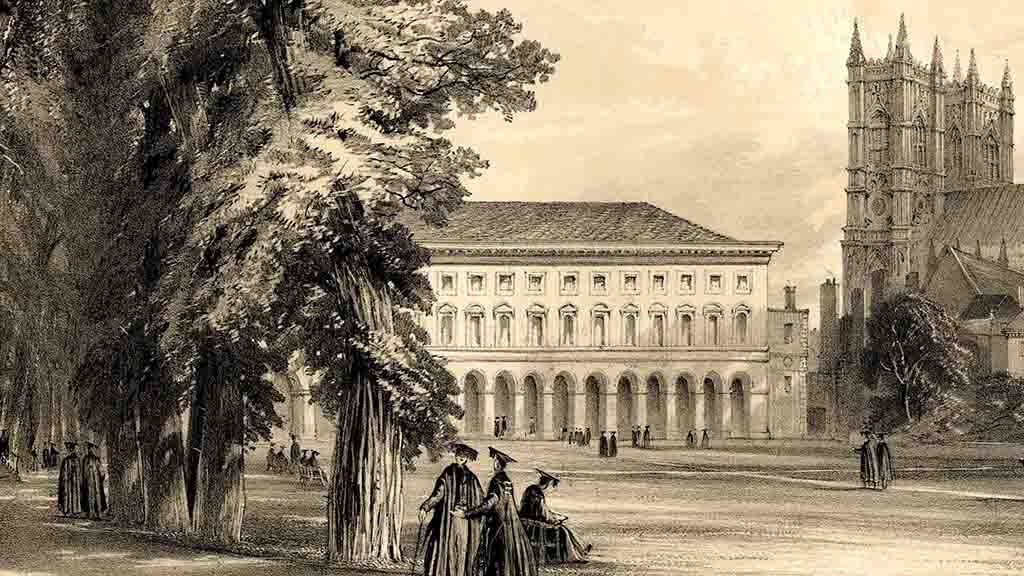

Nestled between the cloisters of Westminster Abbey, School and Ashburnham House lies a little treasure. In perhaps the most valuable square in the country, watched over by the looming presence of perhaps the finest and most important church in the country and the property of perhaps (certainly, really…) the greatest academic institution not to be a university, is a small garden. A sanctuary, amongst the scholarly, political and ecclesiastical hubbub of its surroundings – and quite a fitting one. A preserve of ancient calm, the site of an arcane sport, this site may not compare in grandeur with the larger greens of higher academic institutions, but what it does not have in size and fame, it has in seclusion and secrecy. Here can be found the best view of Westminster Abbey (only paralleled by those higher up in Ashburnham House), and yet, despite the Abbey’s worldwide fame, it is known only to a select few. A very lucky few indeed.

The space that Ashburnham Garden now occupies was formerly the site of the monastic frater – the refectory used to eat meat by the Benedictine monks of the Abbey, which allowed them to circumvent the ban on the consumption of meat (Rule of St Benedict 39:11). This would have been a grand place, stretching the entirety of the present Garden, with a dais at the east end. It was constructed in the XI century under the oversight of Gilbert Crispin, Abbot of Westminster 1085-1117, hence the rounded Norman arcade still visible today. The windows above this were probably added in the XIII[1] century under the Abbot Nicholas Litlyngton (note the Gothic pointed arches). The Gothic rose window of the Abbey, slightly obscured by the glistening trees is perhaps the best remnant of the mediaeval aesthetic that would have accompanied clerics and the earliest children at Westminster. It is a testament to the garden that such a place should be found in the bustling centre of a cosmopolitan metropolis. The former roof was held up by ‘angel corbels fast becoming unrecognisable’1. Indeed they now just look like protrusions of stone with some faint design, but above the works department storage room, on the far west, between the wall and the fives courts, remains one, sheltered from erosion, clearly showing the form of some beast. Ashburnham Garden and indeed the rest of the school is awash with such small features which have quite possibly gone unnoticed for centuries. The frater was finally demolished in 1544 after the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

The angel corbels supporting the frater roof. The bestial outline of the furthest can be seen.

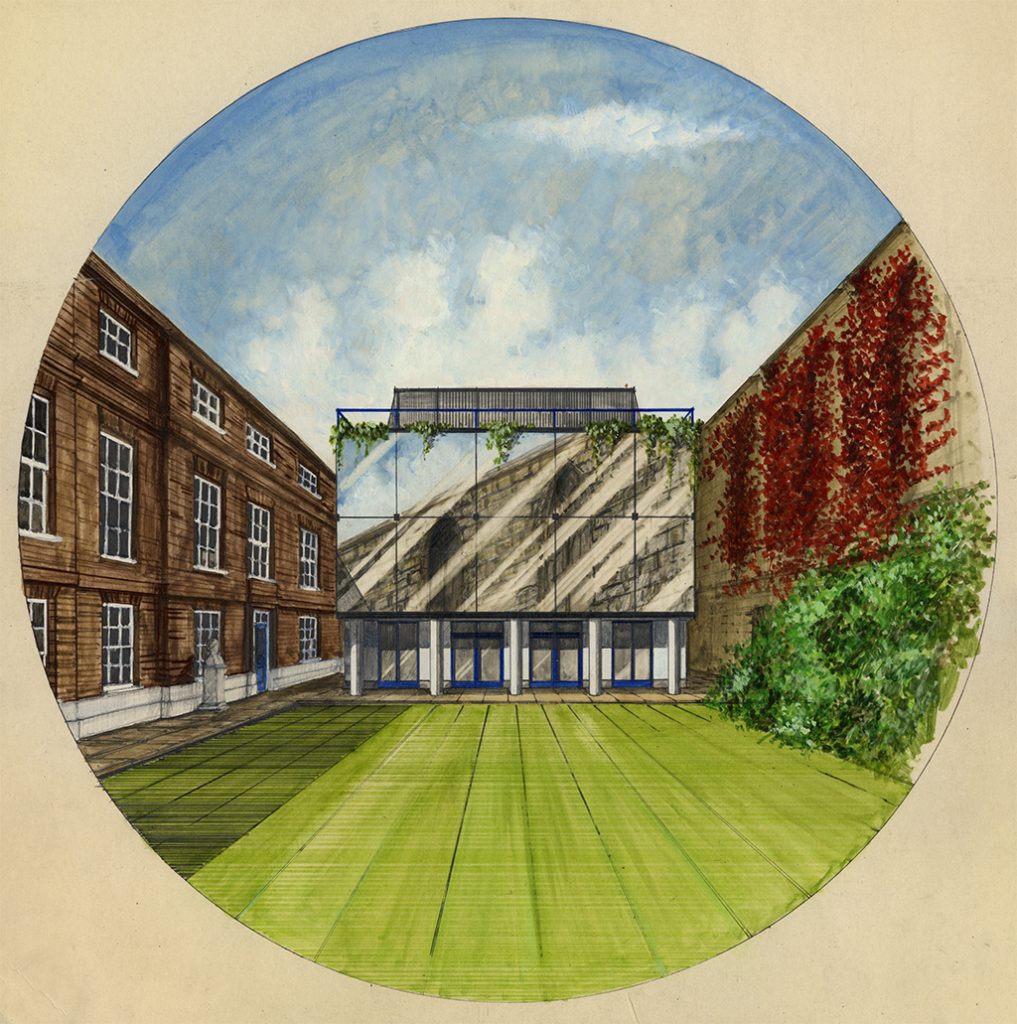

It was once proposed that a building of classrooms should be built where the current Fives courts are. So as to fit in, the windows would be covered in mirrors reflecting School.

On the west side of the garden are the fives courts. This arcane game was invented at Eton in 1877, the shape of the court is modelled on the buttresses of Eton College Chapel. The courts, previously in what is now the day house Hakluyt’s were built in the 1960s, replacing a rather unbecoming carpentry shop. Perhaps this is emblematic of its period: it seems from photographs that from the school’s acquisition to only recent times Ashburnham Garden was not a particularly nice place – it looks dreary without any trees to cover some of the north wall and there is always some clutter or other on the short grass enclosed by a fence. Next to the courts, by the frater wall is the statue of reformist politician Francis Burdett (OW).

Ashburnham Garden for most of the XX century was not a very exciting place.

On the south side of the Garden is Ashburnham House itself – the owner would have had Ashburnham Garden as his personal garden. Currently on the ground floor abutting the Garden are the Gibbon Room, used for the storage of classical grammars, many written or belonging to XVII century Head Master Richard Busby, the Hastings Room, a small kitchen and a Maths classroom, in front of which is the flagstone dedicated to former Head Master Stephen Spurr. Above these are the Library and the rest of the Maths Department. On the east side is School and the steps up to the back entrance and the Toplady Room, a secondary Maths classroom. Beneath the Toplady Room is the Abbey’s Dark Cloister, which has windows looking out onto Ashburnham Garden and two stained glass windows dedicated to Robinson Duckworth, Sub-Dean from 1895-1911. There is also a small quizzical alcove concealing a little bench.

The area of Ashburnham Garden has only been an open space since the refectory was demolished in 1544. It is said that that the stones were given to Edward Seymour, Lord Protector of England from 1547-1549. The House itself became the Dean’s residence when Westminster became a Bishopric in 1540 but the Dean moved back to the deanery in 1550 and Ashburnham House went into private ownership: some of its better known owners have been Sir John Fortescue, Chancellor of the Exchequer to Elizabeth I and Sir Edward Powell, Master of Requests to Charles I. In 1662, the eponymous William Ashburnham was granted a lease on the House and in 1730 was leased by his descendant Lord Ashburnham to the Crown for the immensely valuable King’s and Cotton Libraries (an oft-told story is that the Head Master went in his night gown to save the Alexandrian Codex, one of the four extant uncial codices of entire Greek Bible, in the great fire).

View onto frater north wall. The rounded Norman arcade can be seen towards the bottom with the later Gothic ones above.

Under the Public Schools Act (1868), it was determined that the school had the right to Ashburnham House and thus its Garden, the school, at the time very short on space, intended to use the House as classrooms in order to relieve the existing ones and accommodate additional pupils – it was said that College Hall was being used as a teaching space and Masters even had to use their own flats to teach. The Dean and Chapter was anxious not to lose Ashburnham House, then the residence of Sub-Dean John Thynne. It was claimed that the school would demolish or make major changes to an important historical building – the school responded by saying the staircase, which would be preserved, was the only notable part of the House and under Church ownership anyway the roof was taken off and a storey added and the Drawing Room’s dome was removed. In any case the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Buildings and William Morris expressed concern, suggesting that it should remain in Church hands. The Abbey, somewhat dubiously, claimed it wished to keep Ashburnham Garden, saying ‘[we] are…anxious to retain the old Refectory, the north wall of which is still in [our] possession in the hope of being enabled by its retention to enlarge the very limited space which is now available for memorial purposes’, going on to say not having the Garden available for public purposes ‘would widely be felt as a national loss’[2]. In place of Ashburnham House, the Abbey offered 15400 sq. ft of College Garden with 250 ft of frontage onto Great College Street, but the school rejected this, insisting on Ashburnham House. The Dean and Chapter having relented, both the House and the Garden passed into school ownership after the death of Thynne. The summer house, admired and used for teaching purposes by John Soane was demolished. A carpentry shop was built on the west side of the Garden, to be replaced in the 1960s by new Fives courts and a staircase around then leading up the back of School.

[1] L. E. Tanner, Westminster School, p.24

[1] L. E. Tanner, Westminster School, p.24

[2] Minutes of the Meeting of the Board of Governors, December 1881