Article by Elizabeth Wells, Archivist, first published in The Camden, 2012

In the early 2010s, the medium of film came to the cultural foreground. Travelling Light, Nicholas Wright’s 2012 play, directed by Nicholas Hytner at The National Theatre, considered the very beginning of cinematography through the memories of a successful Hollywood director; The Artist, having had unprecedented success at the Oscars, recreated the world of silent film; Tacita Dean’s work, simply entitled Film, payed homage to the dying medium of 35mm celluloid.

My interest in the development of film has been through a much smaller lens, that of Westminster School. I’ve found it fascinating to learn how pupils at the school reacted to this new technology, came to embrace and critically appreciate the medium, and then appropriated it for their own purposes.

In 1914 the school’s Debating Society considered the motion ‘That this House deplores the popularity of the Cinema’. The Proposition described films as ‘vapid and unsightly, and deplored this disastrous influence on the half-educated classes’ also claiming that the ‘flickering of the films was hurtful to the eyes’. Despite these strong arguments, the motion was defeated by 14 votes to 9. Although Westminster pupils occasionally expressed their concern that ‘the vast majority is content to leave its thinking to be done for it by film directors’ (The Elizabethan, 1933), their own enjoyment of cinema precluded any serious criticism.

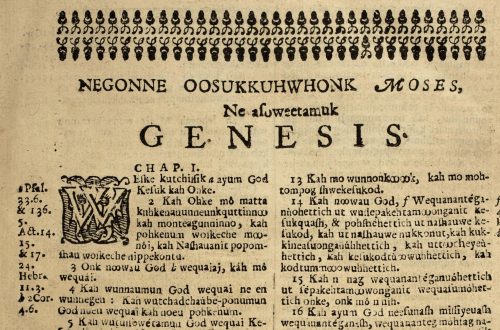

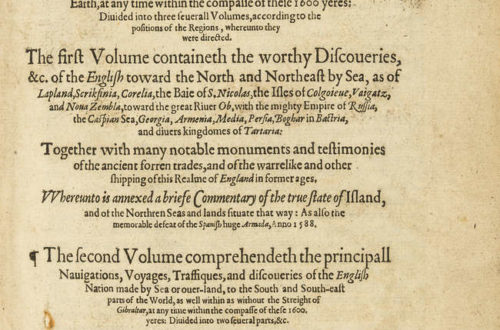

Film makers feature in Latin Play epilogues from as early as 1896, acting as useful dramatic devices to create a (screen)play within a play. As film grows in popularity it also enters the classroom. In 1920, the School’s Scientific Society were lectured on the subject of cinematography and shown a short film. From this point forward watching and making films becomes broadly accepted as a respectable activity. A letter from an Old Westminster at Cambridge in 1936 comments ‘a twelfth cinema is to be opened – even bigger and better than all the others. Now at last the undergraduate will be able to go to a different film every afternoon and evening of the week. At last the problem of living in Cambridge is nearly solved’.

By this point, various Old Westminsters were beginning to experience success in the world of film. Major Court Treat (OW 1904-1908) made pioneering films of Africa in the 1920s. John Gielgud (OW 1917-1921) was both staring in and directing films in the 1940s.

Westminster welcomed many illustrious visitors to talk on the subject of film. Eileen Arnot Robertson, a novelist, film maker and critic, spoke about how to make and evaluate films. In the account of her talk the secretary notes that Robertson’s ‘use of strong terms, which has got her into trouble elsewhere, did not particularly embarrass us (Robertson famously said “I think Bette Davis would probably have been burned as a witch if she had lived two or three hundred years ago”)…she supported her didactic aim with an abundance of illustration, anecdote and humour which pleased everyone’. Graham Greene also spoke on ‘The Subject Matter of Films’, commenting that the purpose of film is the same as that of a novel, to portray ‘life as it is and as it ought to be’.

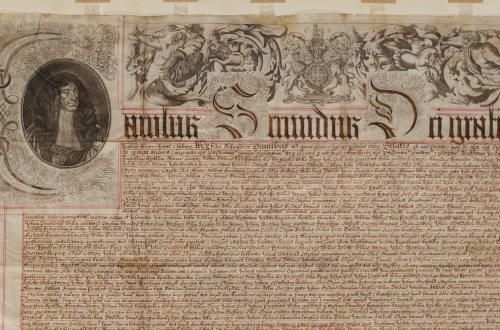

Naturally Westminster pupils became involved in making films themselves once the technology became affordable. In the archive there are over 60 cans of celluloid film. The earliest surviving film dates from 1939 and, although it only lasts a few minutes, includes colour footage of the school. A year later, a film entitled Grant’s Carries On, humorously depicts life during the school evacuation to Lancing College with scenes of boys digging allotments and knitting for the troops.

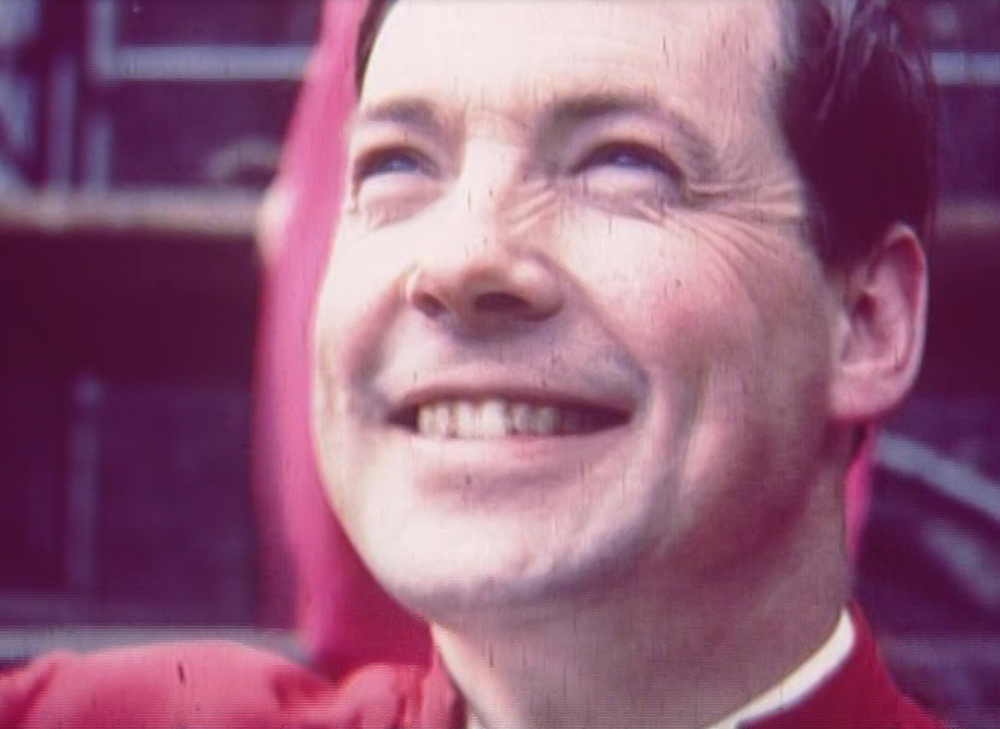

The documentary film making continued into the 1950s and 60s with familiar rituals such as Commemoration and more unusual events, such as the Queen’s Quatercentenary visit, being captured. This awakening was largely due to the interest and enthusiasm of one staff member, Martin Rogers, Housemaster of Busby’s. He helped his pupils form the Busby’s Film Group, which managed the production of a large number of films during this period.

It could happen, but it won’t (1968)

Of course, it wasn’t long before pupils wanted to make their own creative films. A review of the Busby’s Film Group latest film, Record 1959-60, commented ‘the two films already produced have exhausted the supply of good material which the school can provide…if the Group is to remain the vital and animated society it has shown itself in the past year, it must expand and find fresh subject-matter’. Indeed, alongside their documentary projects pupils soon began making their own creative films which often demonstrate a broad range of cinematic inspiration. A thriller entitled December 13th shows the strong impact of Bunuel, the surrealist film maker. Science Fiction is represented in It could happen, but it won’t which imagines the school under an alien invasion and includes some impressive stunts. This film is reminiscent of the 1950s American B-movies such as The Blob and Creature from the Black Lagoon.

In 1970 the longest and most accomplished film was made, involving a large cast including Martin Rogers, then Master of the Queen’s Scholars. Simply entitled Red, an advertisement in The Elizabethan reads as follows:

‘The blood of oppressed and dying College juniors; the tears of a raped girl; the anguish of a tortured Housemaster and the colour red – both that of blood and also of the glorious Communist Revolution. All these are ingredients of the greatest cinematographic marvel of our age: Creative Film Guild will premiere their supreme contribution to the cinema, to art, to life and to history, sometime this term if they remember to use a darkroom when opening the camera’

Thankfully they did use a darkroom and the film survives. Heavily influenced by earlier films of school rebellions such as If…. directed by Lindsay Anderson and Zero de Conduite by Jean Vigo but still funny and original, Red forms a fitting conclusion to this period of the school’s cinematic history.