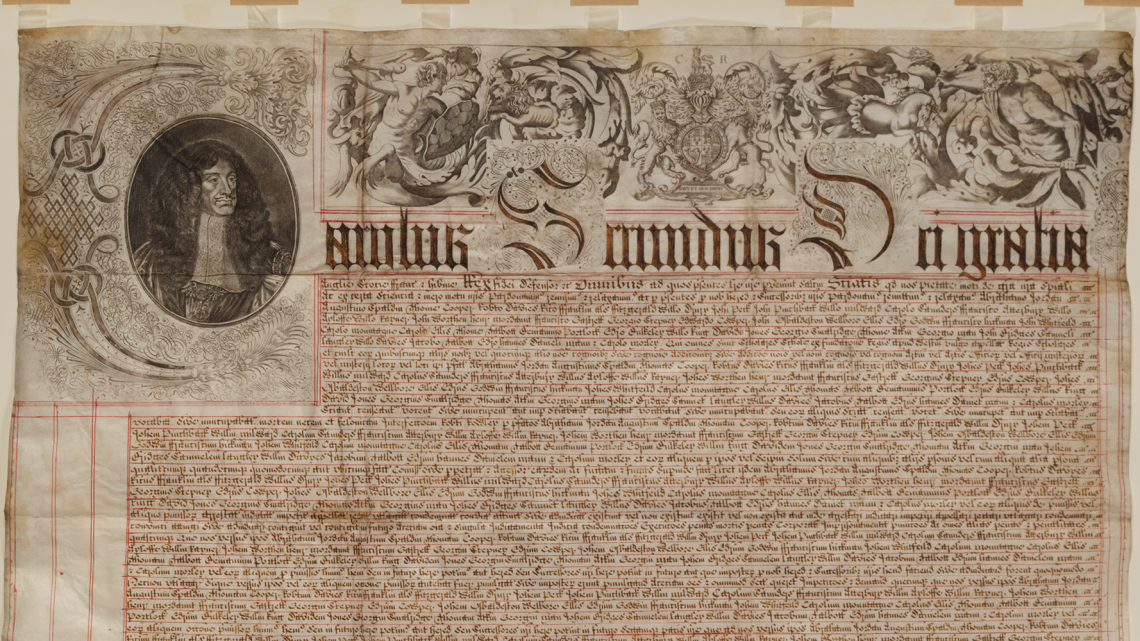

In 1949 Viscount Davidson (OW) purchased at Sotheby’s and presented to the School the so-called King’s Scholars’ Pardon. For many years this hung on the wall of College Library, and it has now been transcribed and translated. In the document, dated 8th October, 1679, Charles II pardons all forty scholars for the murder of one Robert Rowley.

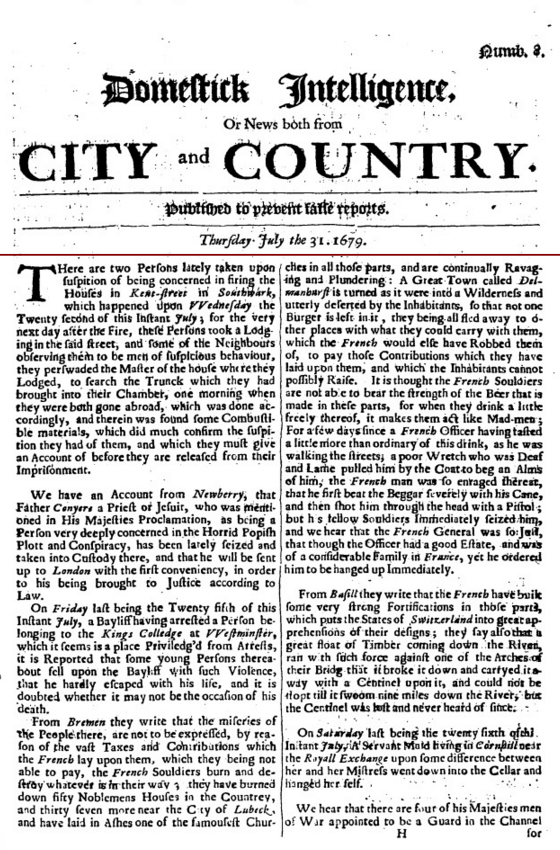

In its edition of Thursday, 31st July, The Domestick Intelligence (a newspaper which was published from 1679 to 1681) reported that on 25th July a bailiff had arrested a person ‘belonging to the King’s Colledge at Westminster.’ In the belief that this was a violation of sanctuary (mistaken – all rights of sanctuary had been abolished by James I in 1623), some young persons fell upon the bailiff with such violence that his life was feared for.

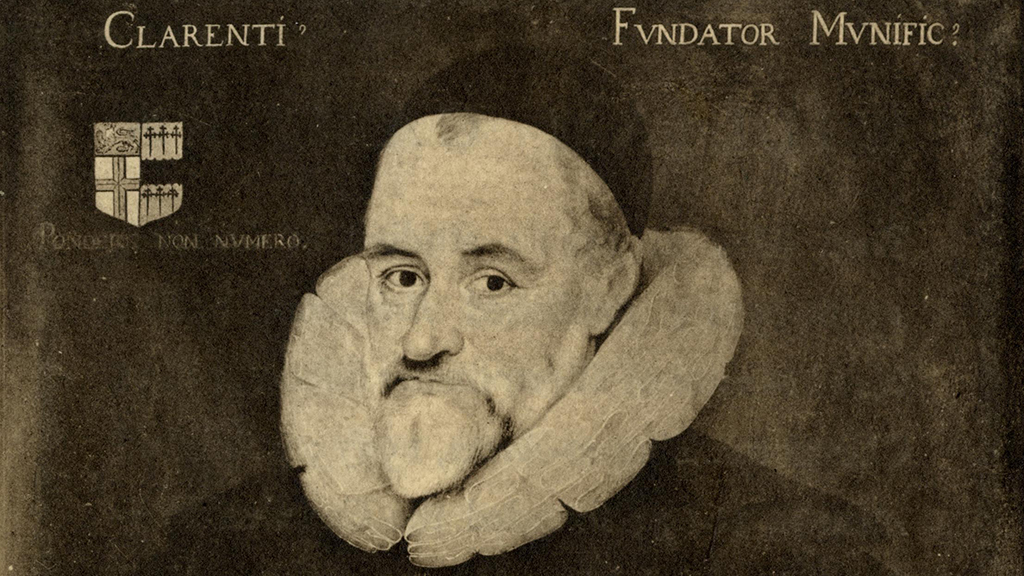

The story is fleshed out in the edition of 19th August, by which time, the bailiff having died, it has become a murder enquiry. The bailiff had taken possession of a house and goods in St Anne’s Lane; a woman, either belonging to the house or a neighbour, had gone to inform the scholars, who were so inflamed that they went immediately with clubs and beat the bailiff so severely that he died a short time after. When the coroner arrived two people deposed that scholars were the murderers; Busby, therefore, was ordered to bring all the scholars into the Abbey, where the witnesses positively identified four of them (of whom one was a son of a peer of the realm). Despite Busby’s assertion that two of the four were with him in Chiswick on the day in question, and despite extraordinary bail being offered, all four were committed to the Gatehouse prison (situated approximately at the entrance to Dean’s Yard), together with the woman (presumably the woman who had gone to fetch them) and some others who had instigated them.

According to the Old Bailey Proceedings the four boys were brought to court on 27th August. They should have been tried during those sessions, but the coroner declared that the evidence was not ready, and that about seven more scholars who were concerned had absconded, so the case was deferred until the following sessions. The absent scholars were presumably at home, since school was normally suspended during August. The court , after considering the ‘youth and quality’ of the four boys in front of them, and ‘to prevent the inconveniencies that might attend their continuing so long amongst ill company in custody,’ granted them extraordinary bail.

The Gaol Delivery Book for August/September lists the following (in order) for the murder of Robert Rowley: Augustine Spalden, William Ayloffe, Francis Gastrell (later Bishop of Chester), Charles Montague (later Earl of Halifax, and ‘founder of the Bank of England’), Thomas Atkins, Samuel Langley, William Davies, Henry Mordaunt, John Osbaldeston, Edward Buckley and David Jones, plus Richard Taylor, Mary Bishop and Elizabeth Bostock (these last three must have been adults from St Anne’s Lane). Beneath is a note concerning sureties, badly damaged and very hard to read, apparently for four people, with three people standing surety of £500 each for each of the prisoners. Mordaunt and Buckley are certainly named, so if the last four scholars named in the Gaol Delivery Book were those who were actually brought to court from the Gatehouse, then the missing/illegible two are Jones and Osbaldestone. Someone called Buckley appears to be standing surety for at least three of them – perhaps the father, or some other relative?

The move to obtain a pardon presumably began some time during August. It is easy to suggest that Busby was behind it, but a more likely candidate is perhaps the family of the incarcerated Henry Mordaunt. The Mordaunts were close to the Stuarts, both before and after the Commonwealth, and had played an active role in trying to bring about the Restoration. Although Mordaunt’s father, Viscount Mordaunt of Avalon, had died four years before in 1675, his uncle, the second earl of Peterborough, was very much a part of the Carolingian court, and particularly close to James. In 1679 he was a privy councillor. (Incidentally, having only daughters, he was succeeded by Henry’s elder brother Charles, the third earl.)

Documents concerning the processing of the pardon are hard to find, although the civil service must have generated many. The King would have informed the Signet Office of his wish by means of a King’s Bill; from the Signet Office the matter would have passed to the Office of the Privy Seal, and from there to Chancery, who would have issued the Pardon as we have it and also recorded an exact copy in the Patent Rolls.

On 15th September we find the earl of Sunderland, a privy councillor, writing to the Clerk of the Signet. The King has heard that the Signet Office are demanding fees from all forty scholars, but thinks it reasonable that fees should be demanded as if for a single pardon, especially since the pardon is only for three or four of the scholars, despite all of them being named.

On 30th September the Office of the Privy Seal sends a copy of the pardon to Chancery, a so-called Warrant to Chancery. Here we find the source of an error which was copied into the Westminster pardon and also into the Patent Rolls. Pardons, like all legal documents, are highly formulaic and repetitious. In lines 12-13 four verbs are repeated in various persons, tenses and moods, and at the end of line 12 we should expect to find, but do not, the word censebatur. In the absence of the Warrant to Chancery one might assume that this is a very common place for words to be omitted, as the scribe’s eyes move on to the next line and he jumps a word in the text from which he is copying. In the Warrant, however, there is a very clear erasure at this point, as if the scribe, perhaps, had misspelt the word and erased it, intending to return later to correct the mistake – he did not.

In the Gaol Delivery Record for October Henry Mordaunt, John Osbaldestone, David Jones, Richard Taylor and two illegibles (presumably the two women) are recorded as having been delivered to the court. The Old Bailey Proceedings gives an account of the trial, which took place on 15th October (exactly one week after the date of the Pardon). The Domestick Intelligence also gives an account in its edition of 21st October; apart from wrongly dating the trial to 16th October, this account is identical in its details to that of the Proceedings, and there are such similarities of language between the two that we can suppose that the author of the Domestick Intelligence article was taking his information directly from the Proceedings.

The Proceedings talks briefly of the ‘fame and rumour’ concerning the (non-existent) right of sanctuary, and also says that the scholars at various times, by might rather than right, had tried to keep out or expel officers like the bailiff. Eight of the eleven scholars pleaded the pardon – the seven who had ‘absconded’ from the hearing on 27th August, plus Buckley, who presumably had had enough and did not wish to risk a return to gaol. Why did the other three decide to stand trial? We can only guess, but perhaps the fact of their incarceration made it important for them to clear their names – or important, in Mordaunt’s case, for his family, who were so closely involved with the royal household. Evidence was presented which seemed to place the three of them at the ‘riot,’ but Busby repeated his assertion of 27th August that one of them was with him in the country (it was two on 27th August, so Buckley must have been in Chiswick as well), and no direct proof was made against the other two, so all three were acquitted. The two women, one of whom summoned the scholars and the other of whom invited them through her house, and also a man, who had appeared to urge the scholars on, were all found guilty. (They came ‘to assault the house, wherein the boy was’ – unless the boy is a new and unexplained character, this can only refer to the bailiff, who was therefore very young.)

In the Old Bailey Proceedings we learn that those found guilty on 15th October were sentenced on Saturday, 18th October. Richard Taylor, Mary Bishop and Elizabeth Bostock were sentenced to death ‘for murdering the bailiff at Westminster.’ However, in the Ordinary’s Account of 24th October we learn that, while several of the sentences handed down on 15th October were indeed carried out, ‘the two women and one man touching the death of the bailiff at Westminster’ were pardoned. In the seventeenth century so many crimes carried a statutory death penalty that, in order to prevent a bloodbath, the king would review all capital sentences and issue a free pardon, taking into consideration such things as the defendant’s character, the nature of the offence and the strength of the evidence; whether those who had instigated the King’s Scholars’ Pardon interceded at this point we can of course never know.

There remain two unexplained details. In the Elizabethan article on this matter from February 1926 it is claimed that after the coroner had had all the scholars brought to the Abbey for identification eighteen witnesses were subpoenaed – but the coroner’s records cannot now be found. Secondly, Lawrence Tanner claims that the boys had each to pay £23 1s 8d for their ’proportion of charge of pardon’ – he does not say which boys (all eleven who were named in the charge, or just the eight who actually pleaded the pardon), and he does not give his source for the sum mentioned.

The Pardon has been transcribed, both in Latin and in translated English. Digital copies of the translation are available upon request.