For three generations, the Dasent family sent their sons from the West Indies over to London to be educated at Westminster School. John Dasent (1735-1787), born in Nevis, was admitted in January 1749 and studied until 1751, when he returned to Nevis. He became Attorney-General there, going on to become Chief Justice of Nevis from 1768. Upon his death in 1787, he was still living on the island and was buried there.

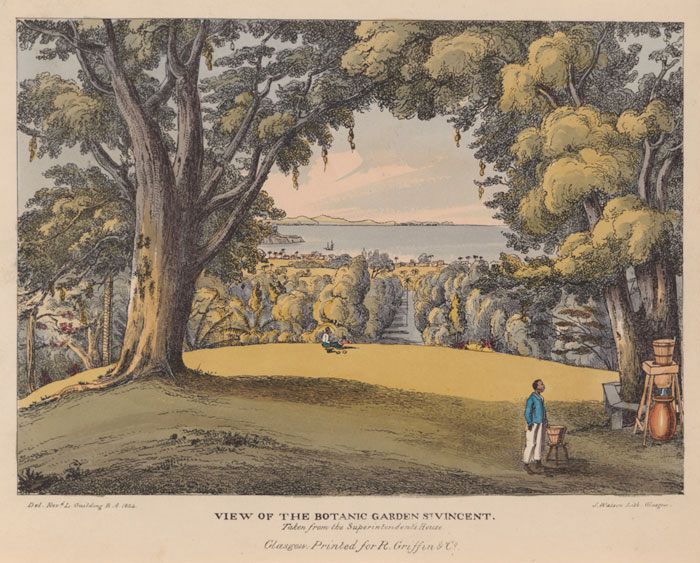

John Roche Dasent was the eldest son of the next generation, born in 1772 and sent over to Westminster School in 1789. He remained in England for longer than his father, but returned to the West Indies to become Attorney-General of St. Vincent. He met his first wife, Harriet Frances Irwin, on the island and had one son, John Bury Dasent, with her within the first year of their marriage. As a result of her choice of husband, Harriet was left out of her father’s will. He disapproved of her marrying ‘contrary to my positive injunction’, and denied her the £5,000 he had intended to leave her. She would have been allowed £100 a year if widowed, but she predeceased her husband and thus never received anything from her father.

After Harriet Frances Irwin’s death, John Roche Dasent married , his first wife’s sister. This marriage took place after Charlotte’s father’s death, so she had already received her inheritance. With no money being given to Harriet, Charlotte had received £8,000, along with some claim over her family’s estate in St. Vincent, which was later registered to her husband. Charlotte and John Roche had several children, three of which were sent to Westminster in a similar fashion to their father and grandfather – John Bury Dasent, Bury Irwin Dasent, George Webbe Dasent, and Alexander Dasent. That the family continued to send their sons back to England suggests a high regard for the education they received at Westminster School.

John Roche Dasent took control of his wife’s family’s estate by paying off mortgages until he was the sole owner of the land and enslaved people, numbering 563 individuals at the highest recorded peak. Through a series of poor financial decisions, the commission agents involved in the sale of sugar from the estate were owed £74,000 that John Roche Dasent could not pay. The plantation was mortgaged to the agents in 1831, and upon the abolition of slavery, the compensation of £8,110 0s 7d was awarded to these agents. John Roche Dasent had already died and, while Charlotte made claims on the estate herself, she was ultimately unsuccessful.

The Dasent family left St. Vincent when the estates were mortgaged and returned to live in England, where Charlotte and John Roche’s three sons were still at Westminster School. John Roche’s eldest son, with first wife Harriet, had already left and was on the path to becoming a lawyer. Bury Irwin went on to become a surgeon, George Webbe became an author and scholar, and Alexander became a priest. Their varied occupations are a microcosm of the spectrum of careers followed by Westminster students.

With their estates in the West Indies surrendered and the slave trade abolished, the Dasent family stayed in England (with the except of George Webbe’s travels to Scandinavia) and continued to send the next generation of sons to Westminster School. George Webbe’s son, John Roche Dasent (1847-1914) went on to write and privately print a family history of the rise and fall of the fortunes in the family in the West Indies. Records of him at the school note him as taking part in a particularly notable Greaze – a Westminster School tradition where the cook throws a pancake over the ‘Greaze bar’ up School, and pupils fight for the largest piece. In 1865, the cook failed to get the pancake over the bar and was thus customarily ‘booked’, with the boys throwing Latin primers. Less customarily, that year the booking resulted in John Roche being hit by the cook’s frying pan. This experience, and the multiple times he was stoned by local boys, could potentially be to blame for severing of ties of the Dasent family with Westminster School in subsequent generations, but the family’s declining fortunes likely left fathers unable to afford the school’s fees.

At the end of his family history, John Roche recounts a trip to the West Indies that resulted in the purchase of his maternal great-great-grandfather’s house:

‘In this house, with two sons in the Royal Navy to carry on their name, the writer and his wide hope to spend the remaining winters of their life, undisturbed by the varying prices of sugar, cacao, cotton, or arrowroot, in a delightful climate, with all tropical luxury, amidst the most beautiful scenery, […] saddened only by the thought that all the estates around him now belong to the descendants and assigns of the mortgagees of the vanished oligarchy of planters, of whom he is now the only male representative in the island.’

It is clear that a bitterness remained within the Dasent family regarding the loss of their estate to agents and that the West Indies maintained some kind of rose-tinted memory of historical prosperity, with a lack of consideration for the terrible history of the slave trade. John Roche Dasent’s two sons didn’t attend Westminster School, and no Dasents have attended since. The arc of prosperity for the family in the West Indies aligns very neatly with their ability and willingness to send their sons to Westminster.