Article by Elizabeth Wells, Archivist, first published in The Camden, 2017

My childhood took place in the window between the collapse of the Berlin wall and the 9/11 attacks. There was much that was wrong with the world in the 90s, but there was also a sense of optimism – a feeling that many of the problems of the past were gradually fading away. Racism, sexism and homophobia were old-fashioned views that in due course would die out completely. In the future gender would be irrelevant, multi-culturalism would render racial identities meaningless and religious fundamentalism would be consigned to the history books. Things could only get better…

*

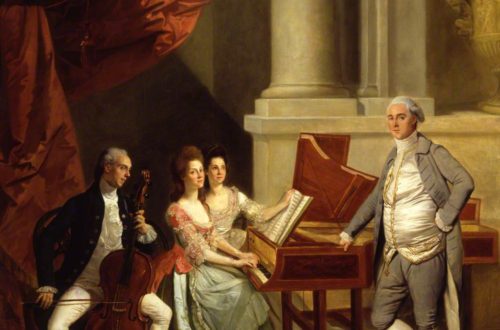

At a Common Room meeting a short time ago, the subject of the school’s ‘aesthetic environment’ was on the agenda. The conversation was wide ranging, but perhaps inevitably there was a focus on the portraiture on display around the school. As Archivist I have oversight of the school’s permanent collection which currently contains 378 works of art. As is often the case, our collection is more a result of accident than design. Some paintings were bought or commissioned, but the majority came to the school as gifts. Provenance was not always well documented. In fact, when a pupil approached me a couple of years ago, enquiring about the subject of a portrait hanging in College Hall, I had to reply that we had no idea who he was or how he had come to be there; he features in our catalogue as ‘Unidentified Gentleman’.

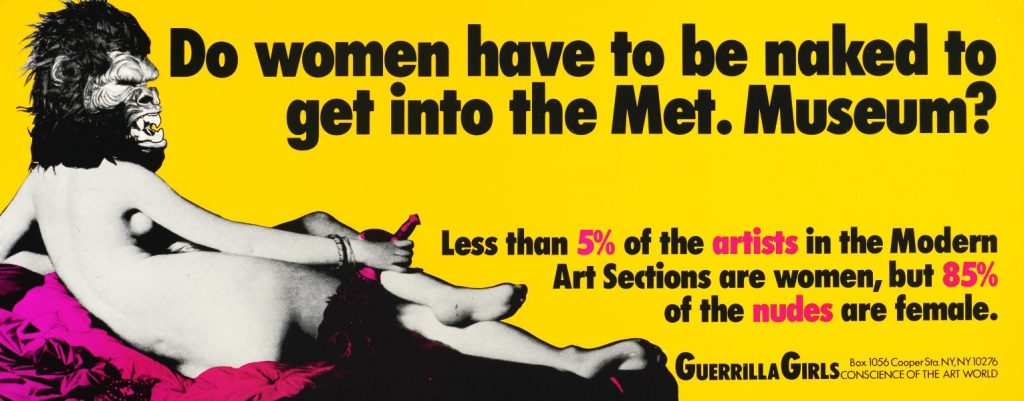

Just over a third of the art works in the collection are portraits and in the past I have jokingly referred to them as my ‘dead white men’. The school does of course have a few portraits of women (Elizabeth I in particular), some of people who are still alive, several portraits of children and a couple of individuals who are not white, but these are in the minority. 102 of our portraits depict white, adult males. Interestingly, there is some hidden diversity as, of 320 paintings in the collection with known artists, over 60 are by female artists. This represents nearly 20% of our collection, a significantly higher proportion than at the Tate Britain or the National Gallery. However, there is no escaping from the fact that the composition of the school has dramatically altered over the last fifty years and our art collection does not yet reflect this change.

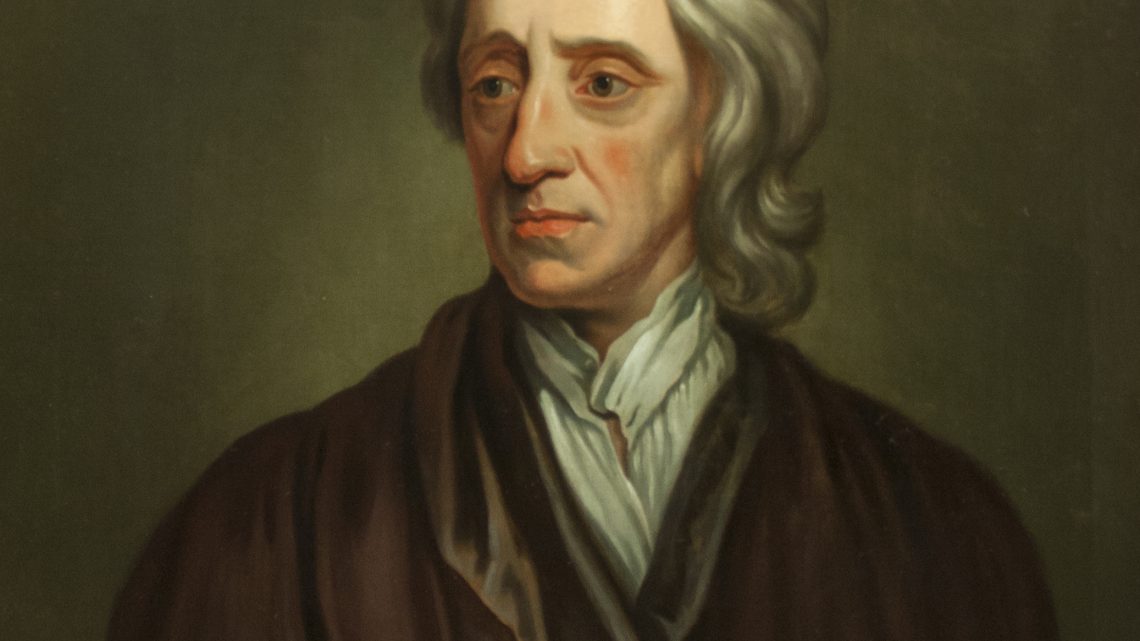

One of my main priorities as Archivist has been to take works of art out of storage and onto the walls. There are 56 more pictures from the collection on display now than when I began working at Westminster 6 years ago, including several more white males on show in the Busby Library, Markham and Bentham Rooms. We’ve added some new pupil art works to the collection, such as Tara Goalen’s portraits of Kofi Arthur and Benjamin Godfrey which hang in the school surgery. But we’ve also added a few more dead white men – purchasing a portrait of John Locke, on display in the Library and a young Dr Busby.

*

*

Contemplating the debate over the school’s artwork has made me consider the symbolic value of portraits. Another vivid memory from my late teens was the televised toppling of Saddam Hussein’s statue at the end of the Battle of Baghdad during the 2003 invasion of Iraq. In Hungary, Lithuania and even Moscow there are sculpture parks full of unwanted busts of Lenin and Stalin, dumped after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

More recently, the Rhodes Must Fall campaign, sought to have statues of Cecil Rhodes removed. Oriel College, Oxford, rejected the demands and Rhodes remains. Many have suggested that the row over the statue was a distraction, and attention would be better focused on other aspects of the Rhodes Must Fall campaign, such as curriculum reform and promoting a more diverse student and staff body at the University. Others have pointed out that the statue was seldom noticed until the campaign began. It is certainly true that putting a picture on display is often an excellent way to get people to ignore it. But the statue’s presence does tacitly suggest approbation. In Germany it is illegal to display portraits of Hitler in public areas for this reason.

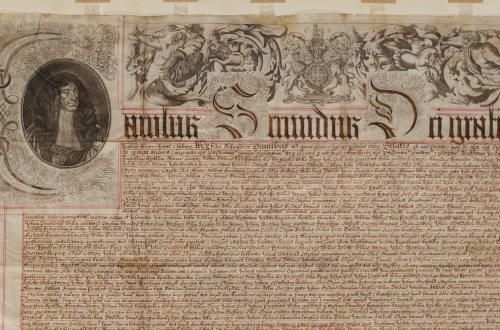

My main concern is the historical absolutism of those wishing to remove art works from the public gaze. Whilst we can rediscover important individuals from the past who have previously been overlooked due to their gender, sexuality or ethnicity, we cannot escape the truth that ‘history is women following behind with the bucket’. Virginia Woolf imagined Shakespeare’s sister whose ability languished as the opportunities available to her brother were denied her because she was female. We can’t remake the past to reflect our current values and to do so would be to create a dangerous myth, to ignore centuries of oppressed people with wasted talents. For the majority of this school’s history all of the pupils and teachers were white and male, and whilst I am glad that this is no longer the case, our collections have to tell this story.

*

A recent cartoon in The New Yorker hit rather close to home. A small child, tugging at his sleeping parents’ duvet announced ‘I had a nightmare that you and Dad woke up one day on the wrong side of history…’

As a left-leaning liberal it is odd to find yourself a bed-fellow with reactionaries, opposing a radical youth movement. The radicals of my youth such as Peter Tatchell, who fought for gay rights, have been attacked and non-platformed by current students. I have been forced to assess whether my position of privilege has rendered me unsympathetic to the struggles of minorities.

*

The tolerant spirit of the 90s was grounded in the belief that gender, race or sexuality did not, or should not, matter. Those who worried about labels were themselves racist, sexist or homophobic: labels are for ‘bad people’, as Game of Thrones actress Maisie Williams recently remarked, when asked if she were a feminist. Now many young people stridently chose to ‘identify’ themselves and demand that others react accordingly. There is often the underlying assumption that this identity should define a person’s political beliefs, an assumption that the recent American presidential election proved wrong. There is a strange contradiction between the hyper-individualism of identity politics and the solipsistic lack of interest for those who feel differently. In the 90s taking an interest in and adopting other cultural practices was an important part of education, building empathy and understanding. Now it is often seen as an act of appropriation: a violent attack by a dominant culture on minorities.

*

Thinking back to the portraits at school I was struck by the guilty realisation of how lazy and reductive it was to refer to my ‘dead white men’. Of course paintings can encourage a superficial glance and a hasty judgement, but a good portrait, properly observed, will tell us much more than just the gender and race of the sitter. I hope that we would all avoid making assumptions about someone’s interior life based on their surface appearance.

The portraits that you see as your walk through the school do not represent an unchanging, homogenous mass. They are your ancestors in the shared heritage of Westminster School. Each is a key to understanding a section of our history. And if elements of that history make us feel uncomfortable, they serve as a reminder of how far we have come and give us courage for the journey ahead.