Origins of the Latin Play

Two beliefs produced and sustained the early tradition of Latin Plays at Westminster in the sixteenth century. First was a faith in the training such performances would offer in deportment and elocution for young gentlemen needing the tools for public life. Second – and it generally came second – was the conviction that such an activity was a necessary part of a classical education. As Latin was the universal language of knowledge, it was deemed essential for it to be mastered colloquially, making drama a tool for instilling the spoken (and living) language. These beliefs were by no means confined to Westminster; the tradition of a pre-Christmas play was a familiar one at many Tudor schools and at the universities, and at Trinity College, Cambridge – our sister foundation – the statutes actually stipulate that the lecturers should act comedies and tragedies each Christmas. Yet it was at Westminster that the tradition stuck, for Westminster that the Latin Play became a defining tradition of the institution – and the history of the Play thus merits rather more attention than it has sometimes received, just as Latin plays as a genre probably deserve a revival, after an era in which the general trend of scholarly fashion has been to focus on the Greek.

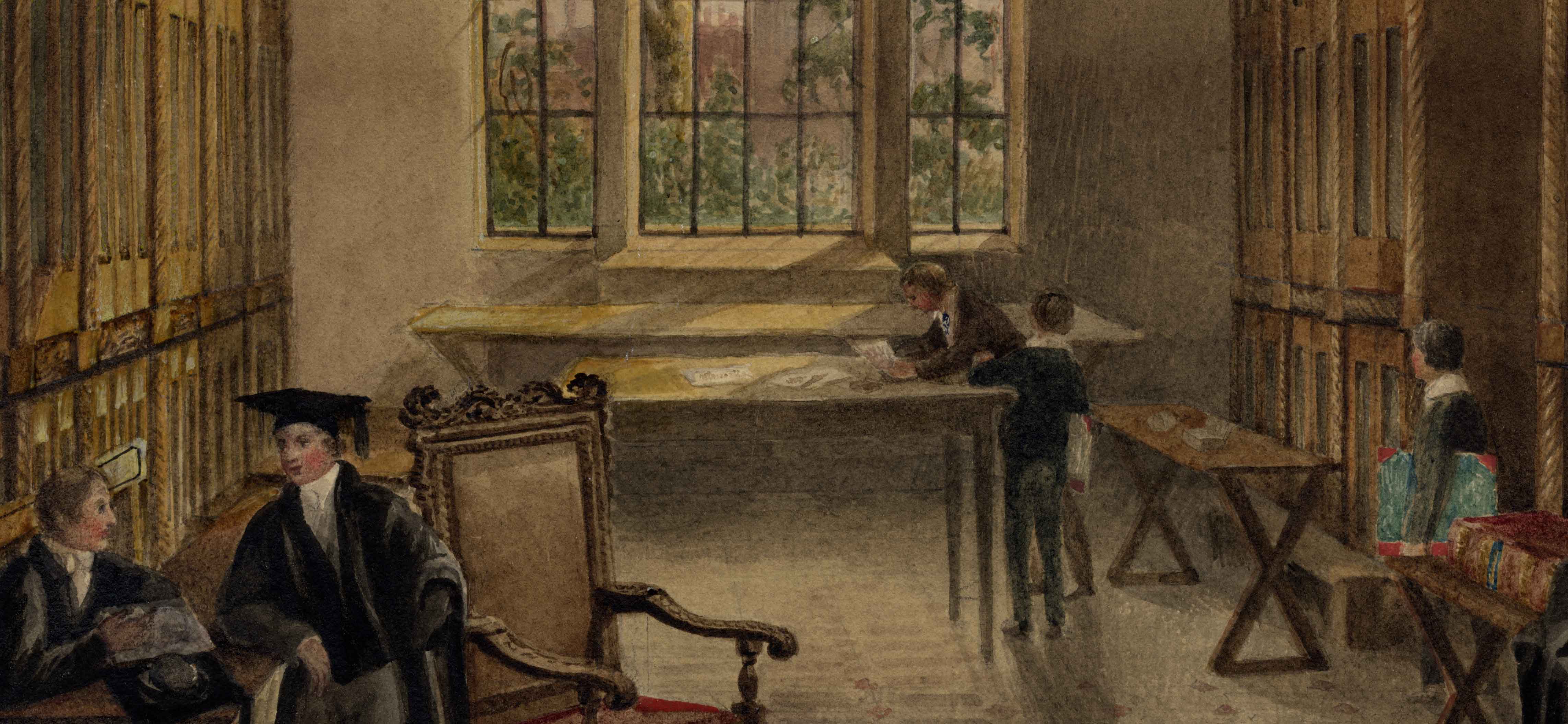

As Head Master, Alexander Nowell had introduced the works of Terence into the Westminster curriculum in the 1540s, due to his belief in the merits of learning the ‘pure Roman style’, and his notebooks contain draft prefaces for the Adelphi, the Eunuchus and Seneca’s Hippolytus, which are likely to date from his pupils’ performances. It was therefore as a confirmation of existing practice, rather than an innovation, that the Elizabethan statutes made explicit provision, de comoediis et ludis in natali Domini exhibendis, for an annual play, to be performed by the Queen’s Scholars in Latin. Nonetheless, this statute was hugely significant – establishing the Play as a regular event, and as the preserve of the members of College.

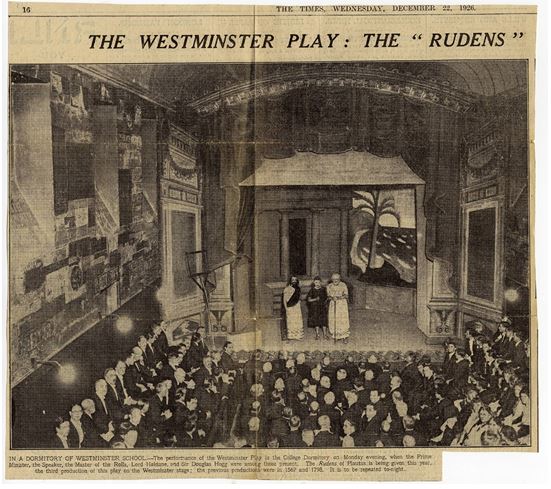

Elizabeth’s own interest in the Latin Play is attested by her regular attendance. In 1563, she gave 25 marks to the performers, and the following year, having been presented with a copy of Plautus herself, rewarded the scholars with a ‘box of comfetts’ and ‘buttered beer for ye children, being horse’ – the latter a regular provision for the time, suggestive of the early emphasis on declamation, rather than ‘acting’ as such. In January 1566, the Privy Council and Princess Cecilia of Sweden joined the Queen in the audience for a performance of Sapientia Salomonis, which was clearly something of an undertaking for the boys. A professional painter was employed to produce the set (the city and temple of Jerusalem), costumes were hired from the office of revels, and a tailor brought in to fit them. One prop was beyond the school’s ready acquisition, so a local woman was paid to bring ‘her childe to the stadge and there attended vppon itt.’ This attention to detail was a regular feature – the following year, for a scene with fishermen in the Rudens, 4d. was spent on a ‘hadocke occupied in the plaie.’

These Elizabethan plays were performed in College Hall – or, when the school left London in times of plague, at Putney or Chiswick. It was, of course, a golden age of English drama, and Westminster boys seem to have been involved in numerous other productions both within and beyond the school. The Town Boys regularly performed plays in English, though these were generally produced out of term time. The Latin Play, however, remained the Play at Westminster, and Treasurers’ Accounts in the Abbey muniments run through to 1632 with annual mentions of the event, confirming that the statutes were obeyed. At that point there is a break in the record, though, and when the accounts resume the Play is missing, suggesting that the Civil War and Commonwealth, not surprisingly, put an end to the tradition for a time.

Presumably Dr Busby was then responsible for reviving it after the Restoration in 1660; certainly he was a keen supporter, having been (despite his somewhat austere reputation) a keen actor in his youth who even considered the stage as a career – in fact, he appeared before Charles I himself in the Royal Slave at Oxford. It is probable, though, that the revived Play was not an annual event, as records are sparse – although we are told that Barton Booth, who later did make a name for himself as a professional actor (and gave his name to Barton Street), appeared in the Andria ‘to great applause’ in 1695. If so, his debut broke the rules, as he was a Town Boy throughout his time in the school, but perhaps his talent justified an exception being made. It is possible, in fact, that a similar exception may have been made for Ben Jonson too. In later generations, cast lists would include the names of Scholars who went on to achieve fame in a wide range of fields, from A.A. Milne to Kim Philby.

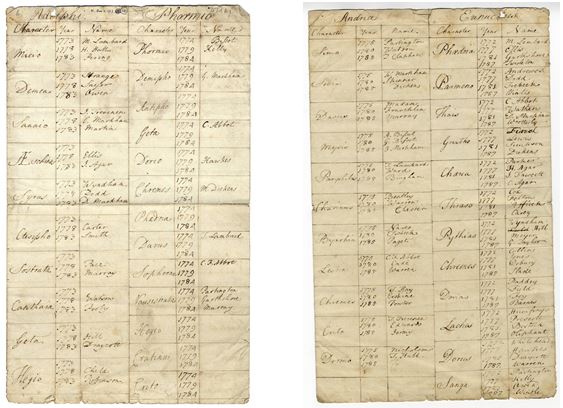

Complete records in the Abbey muniments only date from 1704, and traditionally that has been seen as something of a second ‘revival’ for the custom – but nothing in the accounts for 1704 itself suggests anything unusual or innovative, so it seems unlikely that this was a genuine point of departure. Nonetheless, we can use these records to identify several key trends and traditions, running from 1704 in an almost unbroken line through to the suspension of the Play in 1939.

Repertoire and Content

First there is the repertoire. In the early eighteenth century more variety was included in the cycle, but by 1750 a loose four-play rotation had been established, with the Adelphi, Andria and Phormio generally joined by the Eunuchus until 1860, when its sensitive name brought about its exclusion in favour of the Trinummus of Plautus. In 1907 the Eunuchus was finally revived under the title the Famulus, though in 1926 it was again replaced, this time by the Rudens, performed at Westminster for the first time in 128 years. It was, in other words, a limited repertoire, which would quickly have become familiar to Westminsters and guests.

The 1935 Epilogue mocks the Nazis and offers a commentary on wider European politics

The 1935 Epilogue mocks the Nazis and offers a commentary on wider European politics

But there was one evolving tradition which made every year’s Play unique; there had long been a specially composed Prologue, but to this in the years after 1704 was added an Epilogue, commenting on the year’s events, initially in monologue, later in dialogue involving the ‘characters’ of the Play transposed into a contemporary setting and into modern dress – a topical skit typical of later revues.

This tradition of a witty and scholarly contemporary satire in Latin at the end of the performance owed much to Robert Freind as Head Master, and allowed the Prologue to become a more serious review of the school year, and of the achievements of Old Westminsters in The World. As such, the collected Prologues and Epilogues of the Westminster Play offer a remarkable insight into the concerns and news stories of two centuries of school and national life, seen through contemporary eyes, and with the topics helpfully outlined for non-Classicists in the programme notes – but they were (and to the discerning reader still are) also hugely witty and entertaining. There were times, of course, when a more serious note intervened – in the first winter of the Crimean War, the tone became suddenly sombre at the thought of the many (ill starred) Old Westminsters, under Lord Raglan, in command at the front; and in the late 1930s the Epilogues offer a fascinating glimpse of European politics, and Westminster’s attempt at a humorous take on Nazism, Fascism and Communism. After the Epilogue, the essential loyalties of the school would then be reiterated with the National Anthem

Location of the Play

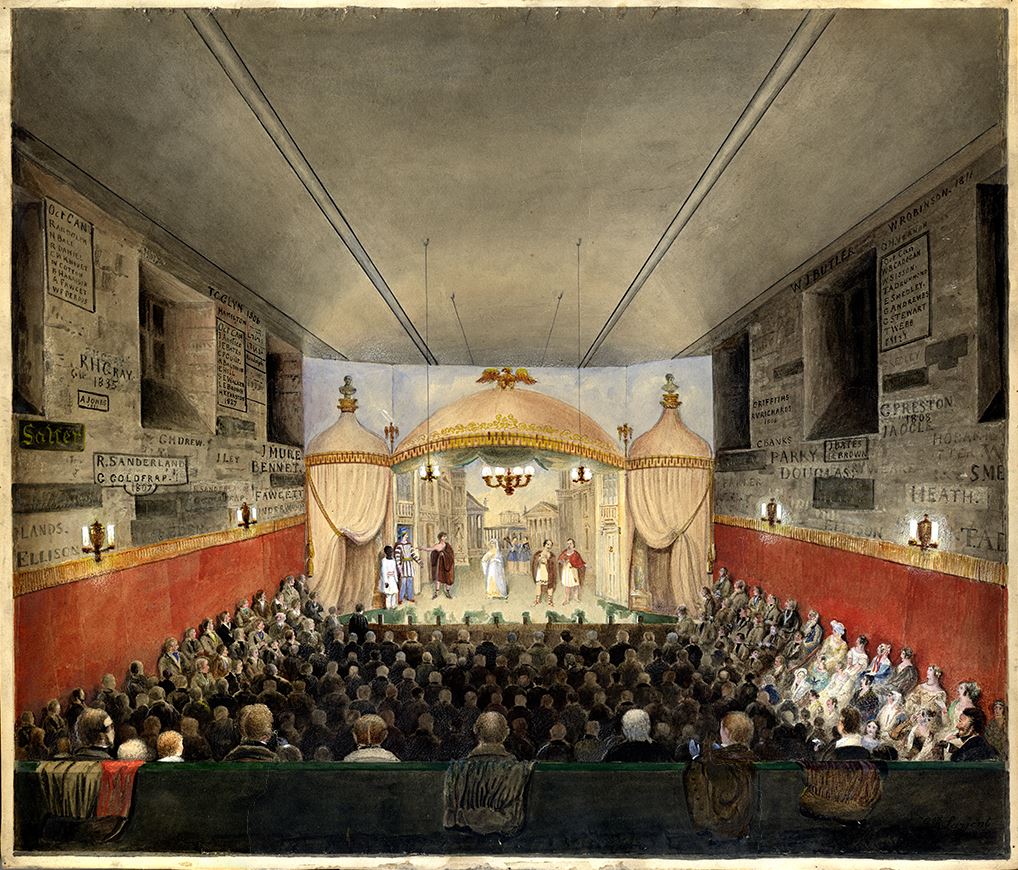

The setting for the Play also moved with the times. Early Latin Plays had been in College Hall, but by 1704 the event had moved to the (old) Scholars’ Dormitory, the former monastic granary in Dean’s Yard. There is a plan of the building, featuring stage and auditorium, in the library of All Souls’ at Oxford. Clearly this location was accepted and beloved, for in the discussions and plans for the new Dormitory facing College Garden there was, from the start, a conviction that the new building would serve annually as a theatre too. The dormitory project was thus intimately linked with the Play – and in 1718, when Samuel Wesley wrote the Epilogue for the Adelphi, he explicitly encouraged contributions for the new building. High wooden beams half-way along the dormitory itself were incorporated in the design, explicitly to support the seating for the auditorium. After a temporary theatre had been put up in 1728, as neither dormitory was in a fit state, in 1730 the new building was used for the Play for the first time. From that point until 1939 the layout for the Play each year changed little, and hence became increasingly old-fashioned, with separate ‘pits’ for seniors, masters and the Head Master’s guests, and the Town Boys up in the Gods, with ‘Gods Monitors’ directing the applause by waving tanning poles. Ladies were first admitted, with their own pit, in 1793, as a compliment to Lady Mansfield, who had two sons performing that year. We are told, though, that Lady Strange beat her to it twenty years earlier, attending disguised as a man.

The construction of the ‘theatre’ within the dormitory each year was a major undertaking, despite the structural help the building provided. By the late nineteenth century, when the vast space of the dormitory had been broken up with wooden partitions into cubicles or ‘boxes’ for the scholars, the process would start some six weeks before Christmas, with the removal of about half of these cubicles to allow the stage and auditorium to be built. The displaced scholars would be forced to sleep in the sanitorium for the duration – a clear disruption to a major part of their school year. Photographs of the construction process from the early twentieth century show the scale of the operation – and in its essentials this had not changed from 1730 onwards.

Scenery and Costume

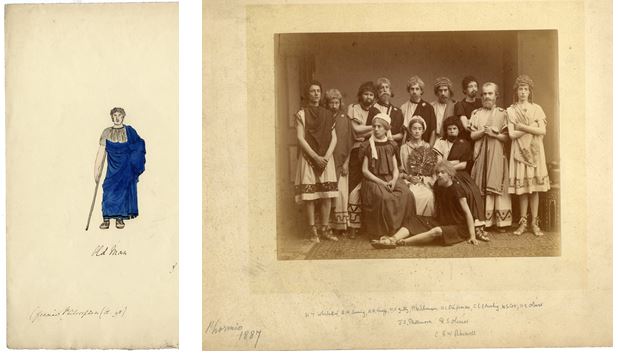

The scenery, clearly, was less flamboyant than under Elizabeth. Two backdrops seem to have sufficed after 1704 – one of Covent Garden, belonging to the Abbey, and a ‘street in Westminster’ used until 1758. At that point a more suitable Athenian backdrop, paid for by Head Master William Markham, was painted by James Stuart. This survived until 1809 when a new copy was made, again funded by the then Head Master, William Carey; this version was apparently stored in the triforium of the Abbey’s north transept until a fire in 1829 provoked a rethink. Although praised at first for its authenticity, and beloved of generations of boys, the ‘impossible mountain with a temple perched on top of it’ was scarcely believable, and in 1858 Charles Robert Cockerell, professor of architecture at the Royal Academy, designed two new backdrops, executed by Fenton – one of the bay at Salamis, the other of Athens and the Acropolis. One or other of these was used every year subsequently until 1939 (except in 1926, when the Rudens required a special set representing a temple by a sea shore) – and after the war, they were put away and forgotten.

The move towards more authentic scenery was matched in costumes. In 1829 the Prologue had condemned ‘sham antiquarianism’, but ten years later the Head Master, Richard Williamson, introduced classical costumes (or ‘Greek drapes’ in the words of the College ledger) for the first time. Previously, the actors had worn a peculiar mixture of outdated but ‘modern’ dress, rather as the daily wear of one century becomes the fancy dress of the next. So, the plays of the 1830s saw the ‘old’ men dressed in the manner of George II’s reign, the young gentlemen in court dress or frock coats, and the slaves as Georgian footmen. The change to authentic costumes had another effect, of course – it threw into sharp relief the contemporary dress worn by the Captain of the Queen’s Scholars in reciting the prologue, and by the actors themselves in the Epilogue.

Audience

Rather more constant was the audience – or its composition, at least. Traditionally, the Dean would attend and preside on the second night, while on the third the senior Old Westminster present would take the chair and call for the ‘cap’ which allowed old boys to contribute to the costs of the production. Many of them seem to have been regular (and deeply nostalgic) in their attendance. An 1857 note tells us that the auditorium would accommodate 340 each night, but 400 or 450 tickets were being issued each year, and Old Westminsters themselves (as well as masters and pupils) did not require one; it was thought impolitic to require them to apply, but they were increasingly encouraged to ‘express their wish to attend’ simply to help clarify the seating required and ‘not to stop any attending…’ – or so it was claimed. A complex system of colour coding developed by the twentieth century, with white tickets for the Gods, mauve for seniors, pink for ladies and white with a red seal for masters.

The pressure on space was only increased by the status the Play achieved; regularly covered in the national press, it was part of the social calendar, and as Lawrence Tanner put it in the 1930s, ‘there are few who have held high office in Church and State during the last 200 years who have not at some time formed part of the audience.’ In 1927, for example, a single performance was watched by the Prime Minister, the Speaker, two former Lord Chancellors, and four high court judges.

Sometimes, as when Warren Hastings attended the Play in 1796, in a rare public appearance in London after his acquittal, the audience could become a news story in its own right. In 1932, less sensationally, but perhaps worryingly for the cast, the audience included 30 members of the Head Masters’ Conference, meeting at Westminster and attending as the Head Master’s guests.

Most notable were the royal visitors, following in Elizabeth I’s footsteps. The young William, Duke of Cumberland – later the infamous Butcher of Culloden – was something of a regular visitor to the school, and treated as a mascot by the boys; he attended the Play in 1727 and 1730, when a Prologue in English was composed in his honour. Frederick, the ‘grand old’ Duke of York, was a regular visitor in the early years of the nineteenth century. William IV in 1834, though expected to fall asleep through boredom and snore throughout, professed himself delighted with the performance, gave £100, and asked not

simply for the customary ‘Play’ half-holiday, but for a whole week, which must have delighted the boys. Other royal visitors included Ernest, Duke of Cumberland (King of Hanover) in 1838, Prince Albert in 1847 (at an extra command performance), 1851 and 1858 – on the latter occasion accompanied by the Prince of Wales – and Prince Arthur, the future Duke of Connaught, in 1867. This was a long awaited visit, as Arthur had intended to come in 1865 but was prevented by the death of Leopold I of the Belgians, and again had to cancel in 1866 as he was revising for an exam (which, the College ledger records, he passed…) Particularly memorable, though, was the visit of George VI and Queen Elizabeth in 1937 – the only visit by a reigning sovereign and consort together – for which the old custom from 1834 was revived, of the Scholars lighting the way to the dormitory with flaming torches, which were later extinguished using the snuffers outside 17, Dean’s Yard.

Cancellations and other threats to the Play

By custom, the Play was cancelled in the year of a death within the Royal family. This happened, for example, after the deaths of George IV in 1830, Queen Adelaide in 1849, Princess Alice in 1878, and the Duke of Albany in 1884 – though the latter was widely felt to be an ‘exaggeration of loyalty’ as the Duke had died in March, and the boys had expected the period of mourning to be over. The same gripes appear when the Play was cancelled for December after the death of the Duke of Clarence in February 1892. Cancellation was, in fact, largely a matter of discretion – in 1884 Dean Bradley had, perhaps precipitately, assured Queen Victoria the play would be cancelled without communicating the fact to the school. Perhaps he hoped that she would assure him such a mark of respect was excessive; after all, William IV’s attendance in 1834 was largely occasioned by such a sentiment as, made aware of the boys’ disappointment when the death of the Duke of Gloucester made last-minute cancellation apparently inevitable, the King declared that the Play should go ahead, and he would attend himself. Nonetheless, the possibility of last minute cancellation clearly kept all concerned on their toes; in 1928, the death of George V was widely, but inaccurately, expected with some alarm. Of course, tragedies within the school could also lead to cancellation – such as the death of the Under Master in 1841; that of little Arthur Liddell, son of the Head Master, in 1853; or that of the Captain of the Queen’s Scholars in Oxford in 1876.

These cancellations were at times worryingly frequent, and suspicious Old Westminsters (and some alert pupils) were only too ready by the mid nineteenth century to believe in plots afoot among the ‘powers that be’ to abolish their beloved tradition. They had a point. When Dean Buckland made such a suggestion after the cancellation of 1846, a massive delegation of old boys, led by the Marquess of Lansdowne, forced him to reconsider. Their names alone take up 15 pages of the College ledger, which records the fear that the 1846 Play had been cancelled ‘in consequence of there being a new Head Master [Liddell] and two new Ushers, none of whom were Old Westminsters’ and that outsiders might destroy what Westminsters held most dear. After the Public Schools Act of 1868 gave the school its independence, matters did not improve. In 1870 we read that there was ‘no Play this year in consequence of the ever-to-be-lamented coming into power of the new Governors; an event which has already effected great and deplorable changes in College… perhaps the Head Master is anxious to prevent thus anything taking place that may resemble what he so feelingly calls an orgie…’

Official concerns did not restrict themselves to the morality of the event. In 1887 a delegation of Old Westminsters protested at the Head Master’s (perceived)attack on the Play as an interference with‘regular school work’ – resorting to phrases such as ‘the sanction of long usage’ and ‘continuance expressly ordered by the regulations’ for good measure. By 1895 the Head Master was so concerned about the manner in which the Play dominated the Scholars’ lives and ate into the curriculum that he cut the rehearsal schedule to after Exeat only, as ‘the Play occupied our minds too much.’ The new plan didn’t last, and soon tradition was restored, with half the Play being rehearsed in each half of term, Head Master’s rehearsals before Exeat and once the stage was set, a semi-dress rehearsal (without make-up) a fortnight before the real thing, and a full dress rehearsal ten days in advance, during prep, with the masters and all Scholars in attendance. Clearly, the concerns about the Play taking over were justified – but for those involved, it was the highlight of their school careers.

The Play in the Twentieth Century

Having weathered these storms of fashion, the Play would finally be brought down by the Second World War. As during the First, the custom was suspended for the duration of hostilities, but after the school returned from evacuation in 1946, fresh problems arose. College dormitory, totally gutted in May 1941, was unusable; and when it was reconstructed, the old space was subdivided, leaving no room for a ‘theatre’. Proposals for a ‘Play Chamber’ as part of the general reconstruction of war-ravaged Westminster foundered on the grounds of space, cost and priority, and it appeared that one of the school’s most distinctive traditions would die. Suggestions for a Latin Play up School, first mentioned in a Prologue by Head Master Rutherford in 1885, when thankfully the obscurity of his Latin meant few picked up the idea, and now revived by John Carleton, once more came to nothing. The revival, when it came, in 1954, was in the open air, in summer, in Little Dean’s Yard – with modern dress, classical pronunciation (not Westminster Latin) and Town Boys in the cast as well as Scholars – but still with Prologues, Epilogues and plays from the familiar repertoire. Most memorably, in 1968, a mini-van ‘apud Fortnum et Masonem’ was winched over the wall from Great College Street into College Garden, and then brought into Yard, to play its part in an innovative Theo Zinn production.

Until the early 1980s, this new tradition continued, in alternate years – but even this then lapsed. But under Jonathan Katz in the 1990s, College started to fill the classical gap, with a series of Greek comedies in English translation, produced as house plays up School – and then in 1999 Latin was back, going against the grain of fashion, with a production of the Adelphi. Nonetheless, 2010’s Latin Play revival sees a welcome return to one older tradition, alongside the new location in the Millicent Fawcett Hall, a Prologue referring to the visits Elizabeth I made to the early Plays, and Dale Inglis’s freshly painted canvases for the backdrop, in the proud tradition of Cockerell. For this year, as we celebrate 450 years of the Elizabethan foundation, the Latin Play returns to its pre-Christmas position in the school calendar, as the right and fitting conclusion of the school’s Play Term.

A scene from the Andria, 1927

This text was written by Tom Edlin to mark the 450th anniversary of the Elizabethan foundation of Westminster School, with acknowledgements to Eddie Smith, John Arthur, Chris Clarke & Giles Brown.

Particular thanks to Rita Boswell and David Clifford for their invaluable assistance.