It was almost inevitable that Edward Wortley Montagu II (1713-1767) would live a less than conventional life. His mother, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, is renowned for her epistolary travel writing from the Ottoman Empire, accompanying her husband when he visited as a British ambassador. She promoted inoculation against Smallpox in the West after witnessing the practise in the Ottoman Empire and campaigned for the process to be adopted back in England, writing to advocate for it under a pseudonym. She had Montagu inoculated in the Ottoman Empire at four years old in 1718, making him one of the first Westerners to undergo the operation.[1] Lady Mary’s unorthodoxy and desire to travel were traits she would later regret passing to her only son.

A man defined by the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography as a ‘traveller and criminal’, Montagu began his life of misdemeanours by running away from school on several occasions. Following in the footsteps of his father, he attended Westminster School under Head Master Robert Freind, although the exact dates of his education are not known. One story of an escape sees him getting as far as Oxford aged 13, in July 1726. Another suggests he ran away in August 1727 and successfully evaded attempts to trace him for several months. His tutor later recounted that Montagu sold fish in Blackwell for a year before discovery; another suggests he took work on a ship sailing for Porto, Portugal, before deserting, working in vineyards, being arrested by the British consul, and eventually being returned to his parents. Whether any or all of these stories are true, it seems certain that Montagu did not receive the typical Westminster education.

It is unclear whether Montagu ran away from Westminster because he did not enjoy his time at the school, or due to wanderlust, but eventually his behaviour pushed his parents too far, and he was sent to the West Indies under the charge of a tutor. According to his own, embellished tale of his life, he spent three years there, but returned to England in 1733 to test the patience of his parents further.

Upon his return, Montagu married a woman known only as Sally, a washerwoman considerably older than his then twenty years. His interest in the marriage lasted only a few weeks, by some accounts, and he left her soon afterwards, although he did continue to pay Sally a small annuity until his death. He remained legally married to her despite this pensioned separation, but the marriage was kept quiet by his family and he was once again sent abroad, while his father received legal advice on breaking the entail on the Wortley estates, with a view to disinheriting his wayward son.

Montagu’s relationship with his parents was strained. He was forbidden from contacting his father until he could ‘act with more prudence than a downright Idiot’.[2] His father was already reportedly paying annuities to two women on Montagu’s behalf, and was being contacted regarding the numerous other debts he had accrued. It is believed that at this point Montagu was in league with highwaymen and was doing little to endear himself to either his father or his mother.

By 1742, while Montagu was spending time in a debtor’s prison, the War of the Austrian Succession was looming. In a series of events that would not be out of place in a smash hit Broadway musical, Montagu obtained an army commission and worked his way up to the rank of captain, distinguishing himself at the Battle of Fontenoy. By the autumn of 1745, he was aide-to-camp to the British commander-in chief. In 1746, he was taken prisoner by the French, later freed by exchange. At the age of thirty-five, Montagu resigned from the army to serve as secretary to the Earl of Sandwich. His language skills made him valuable during the Earl’s negotiations of peace in Aachen following the war.

It was arranged by the Earl of Sandwich for Montagu to be elected uncontested to parliament as MP for Huntingdonshire. He attended the opening of parliament, but his father ordered him ‘to sit on a different side of the House’,[3] and would not meet with him. In 1750, Montagu had to leave Paris on account of a stipulation his father had added to his £1000 yearly allowance: they were not to be in the same city together. For a few years, Montagu lived lavishly, and seemingly beyond his means. Horace Walpole describes him as an eccentric and extravagant figure:

Our greatest miracle is Lady Mary Wortley’s son, whose adventures have made so much noise; his parts are not proportionate, but his expense is incredible. His father scarce allows him anything: yet he plays, dresses, diamonds himself, even to distinct shoe-buckles for a frock, and has more snuff boxes than would suffice a Chinese idol with a hundred noses. But the most curious part of his dress, which he has brought from Paris, is an iron wig; you literally would not know it from hair—I believe it is on this account that the Royal Society have chosen him of their body.[4]

While enjoying this life of luxury, Montagu bigamously married Elizabeth Ashe on the 21st July 1751. Ashe was rumoured to be the daughter of Princess Amelia, second daughter of King George II, although her father is unknown, as is the origin of the family name Ashe. Within three months, Montagu abandoned this second wife, who was then pregnant with his son. Edward Wortley Montagu III, as he would be named, was one of Montagu’s many children.

Possibly to defray his debts, Montagu sought to make money through extortion at Faro (a gambling card game) parties in Paris. Montagu and a group of friends, including fellow MP Theobald Taaffe, encouraged Abraham Payba to part with a large sum of money by plying him with alcohol. When Payba refused to pay, alleging harassment, he was threatened with physical assault and subsequently fled Paris. In return, Montagu and Taaffe broke into Payba’s lodgings and took 50,000 livres worth of jewellery and other valuables. They were subsequently arrested by French authorities. While Payba won a case against them, the ruling was later overturned and Payba himself was arrested and charged with defamation. Both Montagu and Taaffe were cleared of wrongdoing.

Montagu never repaired his relationship with his father and upon his death in January 1761, the bulk of Edward Wortley Montagu senior’s estate was instead left to his daughter, Lady Bute. Montagu was left an annual allowance but was far from pleased not to have inherited his father’s wealth. Lord Bute gave Montagu large sums of money, in addition to an estate of £8000 per year, but when his attempts to challenge the will were unsuccessful, Montagu left once again for mainland Europe.

Upon meeting Caroline Dormer Feroe, the wife of the Danish consul, in Alexandria, Egypt, Montagu convinced her that her husband was dead and married her. She joined him on a tour of Armenia, Sinai and Jerusalem, but later learned that her first husband was still alive.

At some point in or around 1762, Montagu fathered a son: Massoud Fortunatus Montagu. Information regarding the boy’s mother is scant, but her name is often cited as Ayesha and she reportedly lived in Egypt. Some texts suggest Montagu married Ayesha, although as he was still married to his first wife, none of his subsequent marriages were considered legal. After hearing a false report of the death of Sally, his only legal wife, Montagu grew concerned for the money that would pass to only to a legal male heir, under the terms of his father’s will. Although Montagu had fathered at least four children by this time, owing to his original marriage to Sally, none of them were considered legitimate heirs. He subsequently put an advertisement in the Public Advisor on 16th April 1776, stating he had ‘no objection to marry any widow or single lady, provided the party be of genteel birth, polished manners and five, six, seven or eight months gone in her pregnancy.’ When Montagu posted this search for a wife in the papers, he was already unwell. A small bird bone pierced his throat in March and he died from its effects on 29th April, 1776 in Padua, Italy.

It is Massoud Fortunatus Montagu who is perhaps the most interesting individual mentioned in Montagu’s will. He is introduced as ‘my reputed son Fortunatus Montagu (called in Arabic Massoud who has hitherto passed for my slave as he is almost black)’. Fortunatus reportedly looked after his father during his final illness, living with him in Italy. As well as ‘two silver watches’, ‘two metal watches’, all of Montagu’s Turkish, Persian and Arabic books, and the majority of his personal effects, Fortunatus was also left £5000, plus an annuity of £400. Montagu made specific provisions for Fortunatus’ further education:

I do direct that my said son Fortunatus shall after his Arrival in England be boarded in some Country place and that he be taught Arithmetic and to read and write English but not Greek or Latin unless he should desire it and that he be not kept at London or either of the universities of Oxford or Cambridge[5]

It is unclear exactly what Montagu’s intentions were in sending Fortunatus to the country and emphatically not to London, Oxford or Cambridge. While it is possible to interpret this as an attempt to hide his Black son, it is notable that Fortunatus was sent to England. Montagu himself was sent away to mainland Europe and the West Indies when his parents were embarrassed by his actions.

It is also made evident in this passage that Fortunatus could not read or write in English when the will was written in November 1775, amid Montagu’s preparations for a trip to Mecca, when Fortunatus was around 13 years old. Contrastingly, Montagu’s eldest son, Edward Wortley Montagu III, was a King’s Scholar at Westminster School by the age of 11, and almost certainly could read and write in English, Latin and Greek at this stage.

That Fortunatus was not sent to Westminster or educated in English from a young age does not suggest disfavour. Montagu’s other son, George, was also not educated at Westminster, and it seems likely that Fortunatus spent at least some of his childhood with his mother, Ayesha. If she and Fortunatus were residing in Egypt, he would have had little need for English. In bequeathing him all his Arabic, Persian and Turkish books, Montagu insinuates that Fortunatus could read and write in other languages. He himself taught the boy Turkish and arranged for him to be tutored in Arabic.

While Fortunatus has not been the focus of any in-depth historical study, he is often mentioned in articles or books about his eccentric father and is usually noted as having died in 1787. The origin of this date is unclear. A 1954 book on Edward Wortley Montague by Jonathan Curling states ‘Fortunatus appears to have died, at the age of twenty-five, in 1787,’[6] but does not cite any reference for this information. Whether this was the original source, or if the date of death predates the book is thus unclear, however it seems to have been adopted in all subsequent mentions of Fortunatus. Despite its widespread use, this 1787 date is incorrect, as I discovered when researching this article.

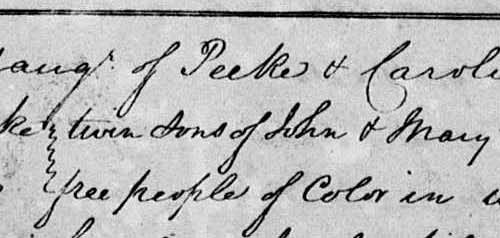

Fortunatus lived for a time with Robert Palmer, the man appointed in Montagu’s will to be his guardian. After arriving in England in June 1776, he presumably undertook the education his father instructed and was baptised in 1779 at Newchurch, Hampshire. Fortunatus lived at Otes Manor, Palmer’s home, possibly up until 1786. Palmer passed away at the end of that year and it is perhaps this death that caused confusion.

The books left to Fortunatus by his father were also brought to England and, as Laurent Châtel describes, were lent out by Palmer:

Montagu brought them back from Egypt; after this death, they were kept by his adopted son, “Fortunatus,” and entrusted to Robert Palmer, the Duke of Bedford’s executor, who kindly lent them to Lady Craven […]. Lady Craven passed on the bundles of manuscripts to [William Thomas] Beckford, who made use of them between 1780 and 1787. In 1786 or ’87, they went for sale.[7]

That the dates of this sale correspond with the date of Palmer’s death suggests there may have been some confusion of ownership, with the books sold as part of a settling of his estate. However, it is also possible that Fortunatus himself chose to sell the books before moving to London, perhaps in need of money or for want of the space to keep them. At least some of the books ended up with John English Dolben, an Old Westminster and schoolfriend of Montagu’s eldest son, who had also obtained the English portion of Montagu’s collection through the death of Edward Montagu III.

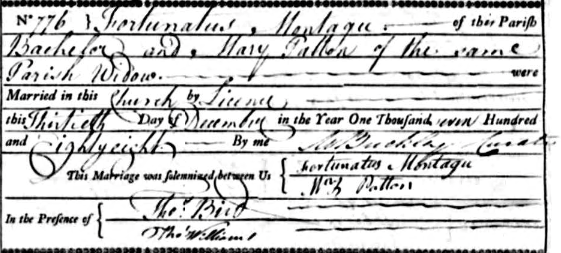

In 1786 and 1787, Land Tax records show Fortunatus renting property from a man named William Worley in Haringey, Hornsey, and by 1788 he had moved to Queen Anne’s Street in Marylebone. On December 30th of the same year he married a widow by the name of Mary Patton. With a name far more common than ‘Fortunatus Montagu’, it is comparatively difficult to research Mary, however she is likely the Mary Allen who married William Pattin in Marylebone in 1780. At some point before December 1796, Fortunatus, and presumably Mary, moved to South Street, Grosvenor Square. Following this they moved at least once more, residing in Frant, Sussex by 1798.

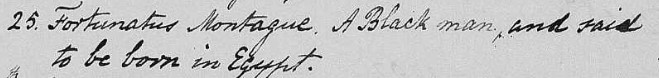

It is unclear why Fortunatus moved so often in England. Whether he inherited his father’s propensity to keep relocating or was constantly trying to outrun prejudice can only be speculated. Fortunatus would die in Sussex in 1798, around the age of 36. In a book of burial records that lists only names for most entries, a note accompanies his that reads ‘A Black man, and said to be born in Egypt’. It can therefore be said with some degree of certainty that this Fortunatus Montagu is the son of Edward Wortley Montagu. He was survived by his wife and left no provisions for any children in his will, suggesting he and Mary had none that survived infancy, if they had any at all. What caused his death is unfortunately not recorded.

Edward Wortley Montagu II left behind a number of letters and maps, as well as his amassed library, but it is surprising there is not more modern interest in his escapades. Dying at the age of 63, he lived a complicated and often nomadic life that could more than fill the screen time of a Hollywood blockbuster, or the pages of a best-selling novel. Where he is known, it is often as a ‘notable eccentric’, which certainly seems like a title none who knew him would have argued with. While Fortunatus’ life was more conventional than his father’s, his peripatetic existence and the mystery surrounding the Arabic library suggests there is plenty still to be discovered.

Update – June 2023

Trinity Fine Art Ltd have recently acquired a portrait of Montagu, with his son Fortunatus. We reproduce the image here with their kind permission.

[1] Dan Snow’s History Hit: Lady Mary and the first Inoculation. 2021. Acast. https://play.acast.com/s/dansnowshistoryhit/ladymaryandthefirstinoculation

[2] Edward Wortley Montagu, Ashe Family, https://www.ashefamily.info/ashefamily/4325.htm.

[3] Wortley Montagu, Edward, jun. The History of Parliament. http://www.histparl.ac.uk/volume/1715-1754/member/wortley-montagu-edward-jun-1713-76

[4] Wortley Montagu, Edward, jun. The History of Parliament.

[5] Will of Edward Wortley Montagu Esq., Ancestry. https://www.ancestry.co.uk/imageviewer/collections/5111/images/40611_309986-00022?usePUB=true&_phsrc=dYz62&_phstart=successSource&usePUBJs=true&pId=466387

[6] Jonathan Curling, 1954. Edward Wortley Montagu 1713-1776: The Man in the Iron Wig. London: A Melrose.

[7] Laurent Châtel, 2013 ‘Re-Orienting William Beckford’ in Scheherazade’s Children: Global Encounters with the Arabian Nights, ed. Philip F. Kennedy and Marina Warner, USA: New York University Press