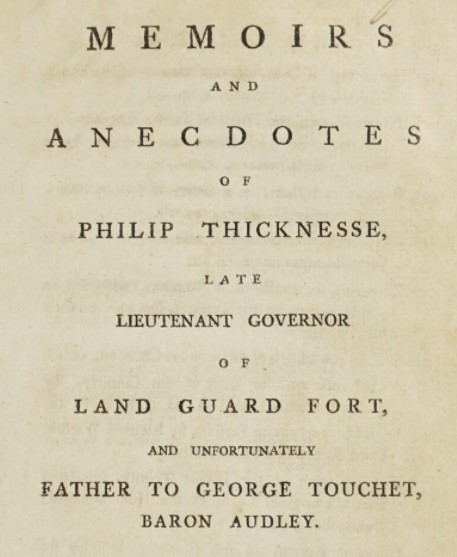

Philip Thicknesse’s twentieth century biographer wrote of him that ‘to anyone who has made a close study of Philip Thicknesse, there come occasions when he can but marvel that nobody ever shot him or bludgeoned him to death’.[1] Two of his sons would end up estranged from him, with the extent of Thicknesse’s quarrelsome nature evident in the title of his own memoirs: Memoirs and anecdotes of Philip Thicknesse: late Lieutenant Governor of Land Guard Fort, and unfortunately father to George Touchet, Baron Audley. An addiction to laudanum likely did little to improve his temperament, and he found himself imprisoned and paying fines for his behaviour more than once.

It was through the benefaction of Head Master Friend that Thicknesse attended Westminster School. He refers to himself as a ‘gratis scholar’, although specifies that he was not a King’s Scholar, suggesting that he received his education for free. Thicknesse’s experience of the school was not a positive one, citing the behaviour of the other pupils and the corporal punishment he received as some of the primary reasons for his unhappiness. He also writes specifically about the favouritism, or rather lack thereof, that he received from one of the Masters due to his lower economic status:

‘Vidal, the usher under whom I was first placed, did not receive the usual presents at breaking up Times, from my mother, as he did from the opulent parents, and the wretch was so mean, as to let that operate to my disadvantage’.[2]

Thicknesse often chose not to attend school and, after a long period of truancy, was expelled and apprenticed to an apothecary. This experience was also not a lengthy one and, inspired by a book he had read, the then sixteen-year-old Thicknesse departed on a ship for Georgia, America. Thicknesse built himself a wooden cabin on an island but found that life across the ocean was not as he had anticipated, and returned to England only a year later. He would eventually be commissioned as a captain at an independent company in Jamaica.

While in Jamaica, Thicknesse found himself involved in fighting back against guerrilla activities of runaway enslaved people. This experience shaped his views on slavery and Black people, with Thicknesse believing that slavery was the natural order of things. He later wrote in his memoirs ‘that the Negroes are a species of the human race, I cannot deny, but that they are an inferior and a very different order of men, I sincerely believe’.[3] He argued that labourers in England, Ireland and Scotland lived a worse life than enslaved people in the West Indies, and was staunchly against the idea of ever allowing Black people to move en masse to England. His racism and xenophobia were views he committed himself to for the rest of his life.

While in Jamaica, Thicknesse found himself involved in fighting back against guerrilla activities of runaway enslaved people. This experience shaped his views on slavery and Black people, with Thicknesse believing that slavery was the natural order of things. He later wrote in his memoirs ‘that the Negroes are a species of the human race, I cannot deny, but that they are an inferior and a very different order of men, I sincerely believe’.[3] He argued that labourers in England, Ireland and Scotland lived a worse life than enslaved people in the West Indies, and was staunchly against the idea of ever allowing Black people to move en masse to England. His racism and xenophobia were views he committed himself to for the rest of his life.

On a leave of absence from Jamaica, Thicknesse was involved in a tavern brawl that became a formal duel, after another man accused him of running away from the guerrilla forces he had been fighting in Jamaica. On the same trip, Thicknesse abducted and married a wealthy heiress. They would eventually settle in Bath and, nine years after she was married, Maria Lanove and two of her three children died after contracting diphtheria. Only one daughter survived. Maria’s parents would die soon after – her father of natural causes, and her mother by throwing herself out of a window at the spot her daughter had been abducted. Thicknesse would spend the rest of his life trying to gain access to their fortune, which he thought he was due, but his efforts were ultimately unsuccessful.

Less than a year after Maria’s death, Thicknesse married Elizabeth Touchet, against her parents’ wishes. She would die three years later after a prolonged illness, and Thicknesse then married the friend who had tried to nurse her through it – Ann Ford. This marriage lasted thirty years and Ann gave birth to six children, four of whom lived to adulthood. One, Charlotte, was later placed and left in a convent in Ardres. Surviving sons George and Philip both quarrelled bitterly with their father. The third volume of Thicknesse’s memoirs is a rare book, as he used it to publicly berate his ‘wretched and undutiful sons’[4] and George and Philip bought and destroyed many of the copies. The volume also contained an order repeated in Thicknesse’s will:

‘I leave my right hand, to be cut off after death, to my son, Lord Audley, and desire it may be sent him in hopes that such a sight may remind him of his duty to God, after having so long abandoned the duty he owed his Father who once affectionately loved him’[5]

These memoirs also expressed Thicknesse’s views on slavery, which The Gentleman’s Magazine commended for their ‘sensible approval’ of the subject.

With Ann at his side, Thicknesse settled in Bath. He bought a cottage and constructed a hermit’s grotto in the garden, making ornamental use of human remains dug up during the renovation of the property. The family made trips to the continent, leaving two other daughters in a convent and entertaining locals with their pet monkey, dressed in a red jacket and boots. Thicknesse wrote and published about the travels, as well as more widely on subjects that interested him. It was on a trip to Italy in 1792 that Thicknesse died from a seizure while in his carriage. Ann was subsequently arrested as a foreigner and spent eighteen months in a convent, but she would live for another 32 years after her husband’s death. She erected a monument to him, celebrating his ‘eminent virtues’, which seem to have been something only she had the ability to see in him.

With Ann at his side, Thicknesse settled in Bath. He bought a cottage and constructed a hermit’s grotto in the garden, making ornamental use of human remains dug up during the renovation of the property. The family made trips to the continent, leaving two other daughters in a convent and entertaining locals with their pet monkey, dressed in a red jacket and boots. Thicknesse wrote and published about the travels, as well as more widely on subjects that interested him. It was on a trip to Italy in 1792 that Thicknesse died from a seizure while in his carriage. Ann was subsequently arrested as a foreigner and spent eighteen months in a convent, but she would live for another 32 years after her husband’s death. She erected a monument to him, celebrating his ‘eminent virtues’, which seem to have been something only she had the ability to see in him.

[1] P. Gosse, Dr Viper: the querulous life of Philip Thicknesse (1952)

[2] P. Thicknesse, Memoirs and anecdotes of Philip Thicknesse, late governor of Landguard Fort, and unfortunately father to George Touchet, Baron Audley, 2nd edn (1790), p. 10.

[3] P. Thickness, p. 176.

[4] Thicknesse, p. 274

[5] Thicknesse, p. 271