Most of the items in the school’s collection clearly fulfil the requirements of our archival collecting policy. Records or artefacts should be related to Westminster School – and concern such subjects as Old Westminsters, former teachers, or the school’s buildings. However, there are occasionally some more anomalous pieces of history. We don’t always know why we have certain items and their journey into the school archive is not as well documented as we would like, if at all. One example of this is the papers of Elias Hicks.

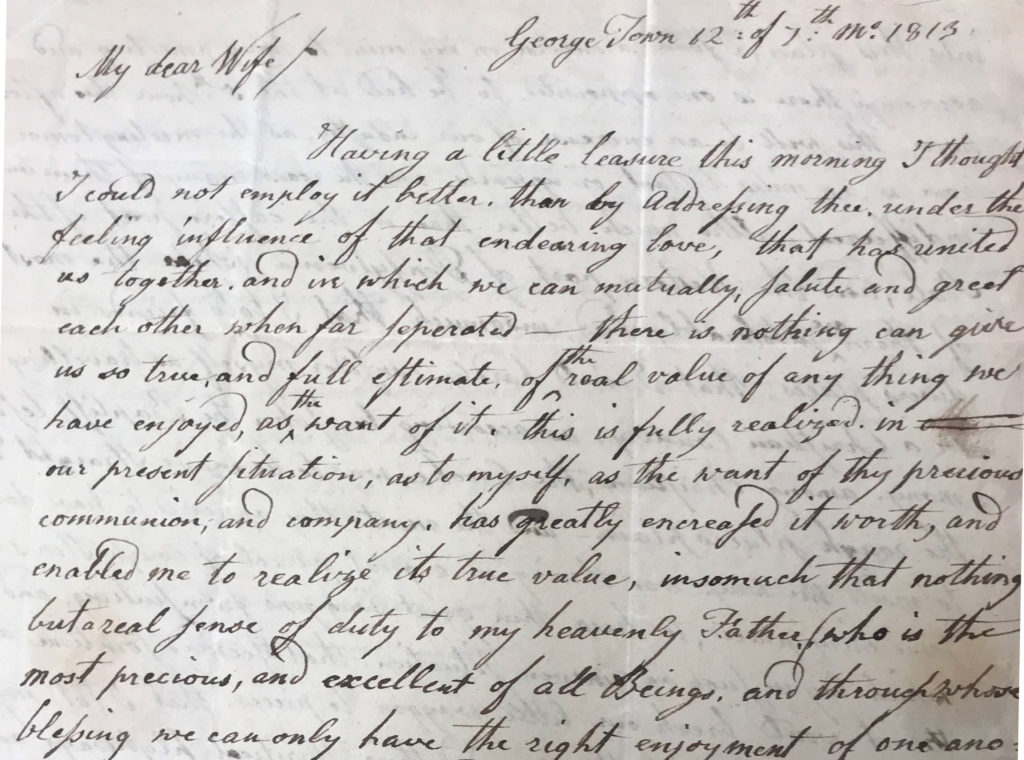

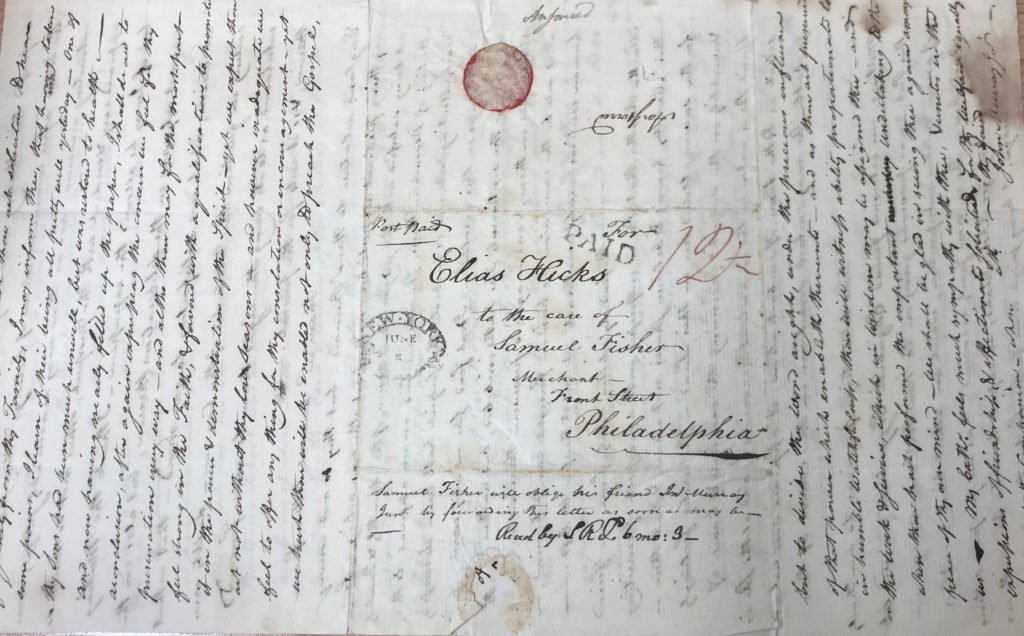

An American Quaker minister, Hicks has no known connection to Westminster School. The papers consist of, among other things, dozens of letters (some from Hicks to others, including his wife, and some from others writing to Hicks), a small number of indentures, and a will. A note indicates they were gifted to Westminster School by a Dr Leon J. Galloway in memory of his mother, Anna M. Dundon. We have been unable to trace a link between either of these individuals and Westminster, so it is unclear why such a donation was made, or when exactly the papers arrived at the school.

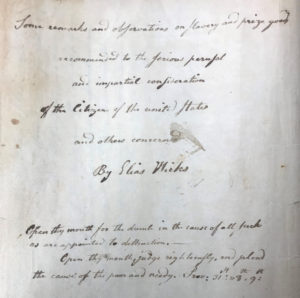

Perhaps the most interesting document amongst our collection of Hicks’ papers is an essay, bound by hand with a copy of an earlier draft of the same work, entitled as follows:

‘Some remarks and observations on slavery and prize goods

recommended to the serious perusal

and impartial consideration

of the Citizens of the united States

and others concerned.

By Elias Hicks.’

This essay first saw publication in 1811, so this manuscript was likely written shortly before. It takes the form of queries and answers that highlight the immorality of slavery and seek to expose the economic structure that was continuing to uphold the practise. While our hand-written copy is slightly different from the version that made it into print, the message of each query is largely the same. The example below demonstrates how innately wrong Hicks saw the practise to be:

‘Query) Does it lessen the criminality and wickedness of reducing our fellow creatures to the wretched and abject state of slaves, and continuing them as such because the practise is tolerated by the laws of the Country we live in.

Answer) No by no means. Because every rational creature knows, or ought to know, that no laws of men, or Nation, can alter the Nature of immutable Justice, nor make wrong, right, nor right wrong.’

In exposing the capitalist roots of the slave trade, Hicks built the foundations on which he proposed a boycott of goods produced through the labour of enslaved people. This boycott would be taken up by the free produce movement, which promoted an embargo of these goods. He made it clear that individual consumers were supporting slavery without owning slaves:

‘Query) By what class of the people is the African slavery principally upheld and encouraged.

Answer) By the consumers of the produce of the slaves’ labour. As there can be no other stimulus or inducement for making of slaves, from the first perpetration of the horrid crime, who take the poor Victims from their friends and Native Shore, to the least consumer, who purchases the fruits of their labour in the varied markets to which it is brought.’

[…]

Query) Does the consumers of the produce of the slaves’ labour who hold no slaves themselves reap any particular advantage by the African slavery.

Answer) They certainly do. Especially in relation to the produce of the West Indies and the Southern States of America, where the labour is principally done by slaves. For was the labour in those parts done by free labourers, it would close much more, than when done by slaves.’

Hicks later wrote a second edition of his essay in 1814, revising his original work and stating ‘I shall only add, as a further apology for the present edition, that the evil still continues: that there are still slave holders, and consumers of the produce of labour of slaves, wrested from them by violence’.[1]

Hicks’ essay was neither the start, nor the end of his advocation for the emancipation of enslaved people. He allied himself with Quakers who were manumitting their slaves, founded a charity to give aid to local African Americans and help provide their children with education, and argued in favour of raising funds to purchase enslaved people and subsequently free them. His work helped expedite the abolition of enslaved people in the state of New York, which culminated with the emancipation of all remaining enslaved people on July 4th, 1827, three years before Hicks died. When he passed away from the effects of a stroke in February 1830, his dying request was that his body not be covered by a cotton blanket,[2] with cotton being the product of slavery. Somehow, after his death, a small collection of his papers would eventually find their way to Westminster School.

[1] Hicks, E., n.d. Observations on the Slavery of the Africans and their Descendants, and on the Use of the Produce of their Labour. [online] The Quaker Writings Home Page. Available at: <http://www.qhpress.org/quakerpages/qwhp/hickslave.htm>.

[2] Calarco, T., Vogel, C., Grover, K., Hallstrom, R., Pope, S. and Waddy-Thibodeaux, M. (2011). Places of the Underground Railroad. USA: ABC-CLIO, p. 153.