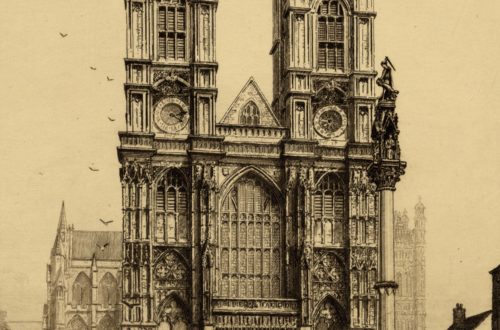

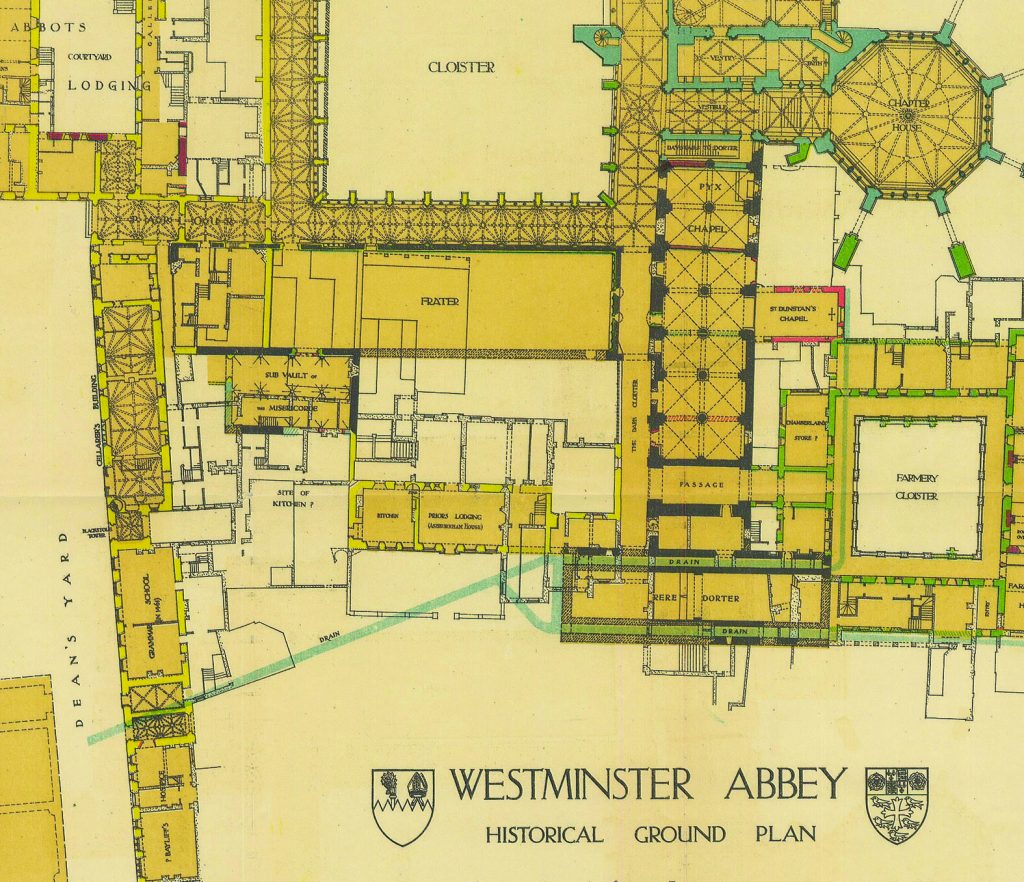

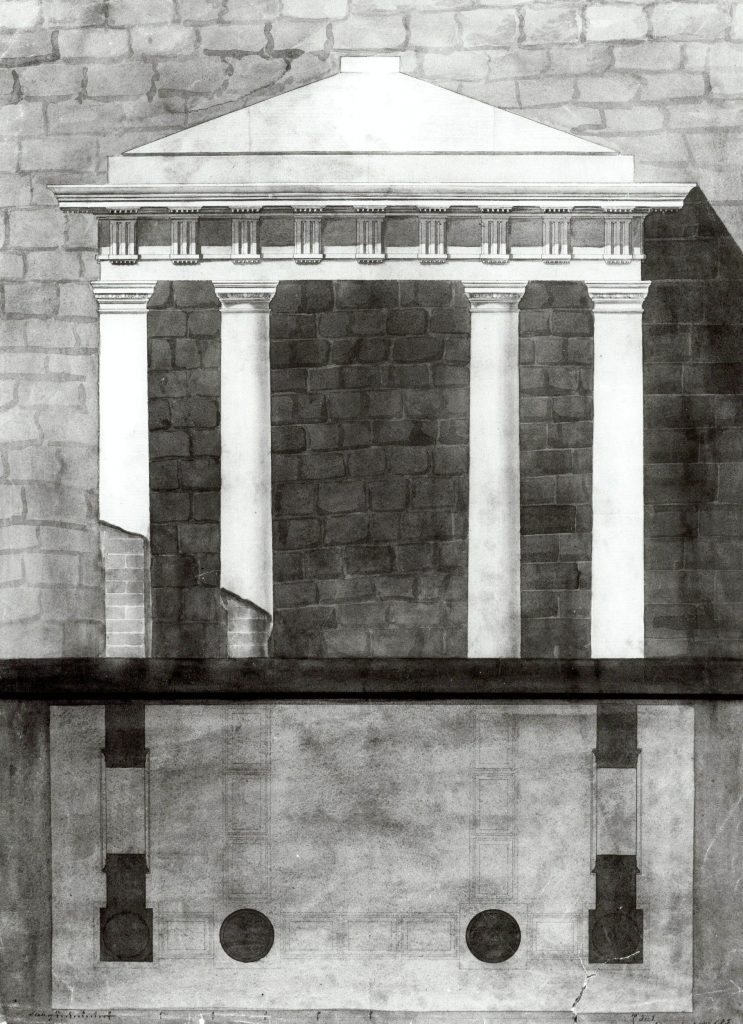

Today, behind Ashburnham House, stands a small, arcane and beautiful garden. Yet at one time this was the site of a grand monastic frater or refectory. All that remains in the present day is its North, East and West walls, the West only a ruin. The exact date of the first foundations is unclear, but it is known that one of the earliest parts of the frater (the plan is shown to the left) was the Norman arcade of the lower North Wall, which was constructed not long after the Conquest by Gilbert Crispin, Abbot of Westminster 1085-1117.

Today, behind Ashburnham House, stands a small, arcane and beautiful garden. Yet at one time this was the site of a grand monastic frater or refectory. All that remains in the present day is its North, East and West walls, the West only a ruin. The exact date of the first foundations is unclear, but it is known that one of the earliest parts of the frater (the plan is shown to the left) was the Norman arcade of the lower North Wall, which was constructed not long after the Conquest by Gilbert Crispin, Abbot of Westminster 1085-1117.

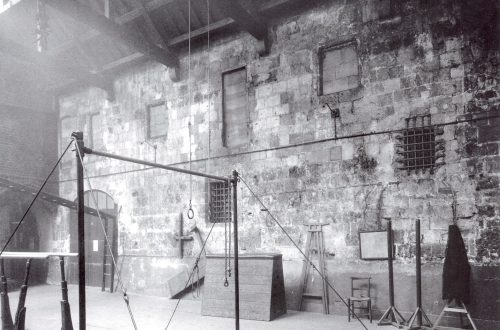

The tiled floor and the since-blocked windows above the twelfth century arcading were built in the fourteenth century by Abbot Litlyngton. The remains of such tiles have been found half a metre below the grass of the modern garden. Behind Abbot Litlyngton’s fourteenth century windows, pictured right, lie the thirteenth century lines of Henry III’s Abbey, which was only completed in the fifteenth century when the Romanesque lines were replaced by Gothic ones. The smaller windows below date back to the eleventh century, when the frater’s roof was lower down. There would have been a raised dais at the East end of the frater, and from Abbot Litlyngton’s fourteenth century rebuild onwards, a room on a higher level would also have been present at this end of the frater. At the West end of the frater, no longer visible but where the fives courts now stand, would have been a second wall built later, perhaps also built in the early fourteenth century after a fire in 1298, in order to make the frater smaller.

The tiled floor and the since-blocked windows above the twelfth century arcading were built in the fourteenth century by Abbot Litlyngton. The remains of such tiles have been found half a metre below the grass of the modern garden. Behind Abbot Litlyngton’s fourteenth century windows, pictured right, lie the thirteenth century lines of Henry III’s Abbey, which was only completed in the fifteenth century when the Romanesque lines were replaced by Gothic ones. The smaller windows below date back to the eleventh century, when the frater’s roof was lower down. There would have been a raised dais at the East end of the frater, and from Abbot Litlyngton’s fourteenth century rebuild onwards, a room on a higher level would also have been present at this end of the frater. At the West end of the frater, no longer visible but where the fives courts now stand, would have been a second wall built later, perhaps also built in the early fourteenth century after a fire in 1298, in order to make the frater smaller.

Important moments in history have often taken place in the garden or the frater which stood there. It was announced on 27th May 1162 in the refectory to his electors that Thomas Becket had been unanimously elected Archbishop of Canterbury, and the barons of England met in the building in 1312 in order to plan how to dispose of King Edward II’s favourite, Piers Gaveston. Most famous of all is a meeting of the Clergy in the refectory in 1294. The King of the time, Edward I, was present and ordered half the Clergy’s revenue to be given to him under penalty of outlawry for refusal. In the dramatic scene that followed, William of Montford, who was Dean of St. Paul’s, collapsed and died at the feet of his sovereign after trying to protest.

Important moments in history have often taken place in the garden or the frater which stood there. It was announced on 27th May 1162 in the refectory to his electors that Thomas Becket had been unanimously elected Archbishop of Canterbury, and the barons of England met in the building in 1312 in order to plan how to dispose of King Edward II’s favourite, Piers Gaveston. Most famous of all is a meeting of the Clergy in the refectory in 1294. The King of the time, Edward I, was present and ordered half the Clergy’s revenue to be given to him under penalty of outlawry for refusal. In the dramatic scene that followed, William of Montford, who was Dean of St. Paul’s, collapsed and died at the feet of his sovereign after trying to protest.

The frater remained at the site until the Dissolution of the Monasteries under King Henry VIII. It was knocked down in 1544, “forthwith in all haste for the avoiding of further inconveniences” (Abbot’s House, an account of the time by Dean Armitage Robinson quoting Chapter Books). The roof was taken off and walls were ruined. The old stone-work of the Norman arcade is now heavily weathered and part of it was cut away in the seventeenth or eighteenth century to make a doorway which has since been blocked up with bricks. The area has been the garden of the Dean’s House and Ashburnham House ever since, and there used to be a seventeenth-century summer house near the Refectory Wall, positioned on a terrace which took up much of the garden. What we now call Ashburnham House became the property of Westminster School when the Public Schools Act of 1868 gave the school the right to buy it. This included the section of it that joins onto School, then known as “Turle’s”, and of course Ashburnham Garden. The school took the decision to remove both the terrace and the summer house in 1882, both pictured below. A carpenters’ shop followed in 1901. Other than these, there have been relatively few changes made to Ashburnham Garden in its history.